I've quoted Jake Smart's Pod Practice appearance in a previous post, but another moment from that episode has been stuck in my mind as well. The hosts ask Jake to speak a little about offensive structures in general, and this is what Jake chooses to focus on:

I'm pretty anti- the concept of clearing. To use a coding term, clearing, in an offense, is a "code smell". What is a clearing cut? A cut that's sole purpose is making space—to get out of a threatening spot, and to move in a non-threatening way. If your goal is to create space on the field, you need to be creating threat in order to do that." [I edited this slightly to make the meaning clearer]

He adds slightly later:

I think zone offensive principles are applicable in a person defensive environment...

Wikipedia says "a code smell is any characteristic in the source code of a program that possibly indicates a deeper problem." In other words, Jake's saying that a team using the term "clearing" is an indication of a team playing sub-optimal offense.

I've written an article in the same vein—Clear out, don't check out—although I didn't go as far as saying don't clear out. I'm surprised there hasn't been more talk about Jake's comments, given how prevalent the concept of "clearing" is in frisbee. Why aren't people talking about this? Perhaps its a case where great players have realized this already and mediocre players aren't obsessively watching frisbee podcasts.

Anyways, I've been thinking about those two concepts and I want to point out a technique I see Brown using that highlights how Brown uses space differently from most other teams. Are the clips below examples of what Jake's talking about in the above quote? Sort of yes, but sort of no. Perhaps this is all more just "what I think about when I think about Brown's offense"1.

Slowing at the saddle point

To make up a term, I'll call what Brown's doing slowing at the saddle point.

There will be copious video clips below, but I'll start by explaining the theory in words.

To get the easy part ("slowing") out of the way before I discuss the complicated part ("saddle point"): as I've written before, separation from a defender happens when you change speeds. So slowing down is a powerful cutting technique—it gives you a chance to get open again. That's why I've written that "Cutters who really know what they're doing have a "herky-jerky" quality to their motions that less effective players lack."

OK, now what do I mean by saddle point? It's a name I've made up (or borrowed from math in a semi-relevant analogy, at least) for a point downfield where a cutter is roughly an equal threat to cut in both directions.

So where is this point? It's on the open side of the field—i.e., a number steps to the opposite side of the thrower from where the mark defender is. It's the spot where you have space to either (a) cut towards the break side and catch a skinny break without forcing the thrower to attempt a super difficult throw, or, (b) cut further to the open side to catch a pass there.

The depth isn't so important, and changes based on context—how many yards you need to gain, how far away other defenders are, etc—but is generally 5 to 15 yards downfield.

Over and over again in Brown's 2024 championship run we see a Brown player getting to this saddle point, slowing down, and then exploding into a cut in either direction (sometimes juking one way then going the other, sometimes more of a "slow-n-go").

A key concept to remember: when you only have one option, you actually have zero options. If the defender has no uncertainty about your plans, you're going to have a tough time getting away from them. I certainly don't mean to suggest this isn't a well-understood concept. We see it elsewhere in frisbee:

A cutter at the back of the stack threatens both deep and under cuts. The possible downsides? Deep cuts require great throwers and are inherently riskier. And under cuts that start so far away from the thrower are vulnerable to other defenders getting in the way.

A cutter in the handler space threatens both catching an upline throw or a swing pass.

But the problem with a strict "cut and clear" system is that it puts all the responsibility on the system to get people open. If all the system lets you do is commit hard in one direction then clear out, you can't take advantage of the physics of change-of-direction — and your team is left with one less way to get people open.

Brown's "saddle point" usage is a unique—to me—twist on this "multiple options" concept. It's not that dissimilar to a "cut from the front of the stack" style, but the ways it's dissimilar make all the difference.

Some examples

More theory below, but for this section I’ll just include a short description of each clip:

Jacques cuts out of a stoppage, then Yut cuts (note how he's just moseying downfield until he's in his spot), then Jacques cuts again (note how he cuts hard through the point, but instead of clearing, circles back around to the saddle point):

Jacques slows down, then continues up line w/o getting the disc. After Yut gets it, Leo slows, then fades towards the sideline. Then Yut moseys to the spot from the backfield, cuts upline but the pass misses:

Jacques asks someone to get out of the way so he has room on both sides to work. Leo throws to him then skips downfield for the return pass. When he gets it and turns downfield, Yut is in front of him so Yut goes to work. Then Leo gets it back and Jacques is in the spot:

Leo jogs to the spot then makes his move. Jacques jogs to the spot, falls down, then gets up and makes his move:

Leo shuffles a few steps towards our left so there's more space to attack back to the right. Then Jacques and Yut both head for the space:

Cal gets to the spot, slows, and goes break side. Leo heads to the spot, slows, and Cal hits him with the lefty backhand. Cal (from the backfield) and Yut (from downfield) both start to move to the saddle point, Yut lets Cal have it.

A twist on 'strong and weak space'

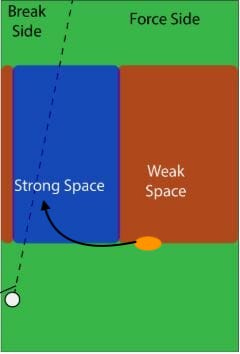

In one of the most-read strategy articles on Ultiworld, Joe Marmerstein diagrams the 'strong' and 'weak spaces on the field. His main suggestion is that "we want to attack into strong space from weak space.". That's great advice that I use every time I play frisbee. But Brown also shows us how there's another option. Their "saddle point" strategy is: get so far into the strong space that you're a valid threat to cut multiple directions—and still be in strong space.

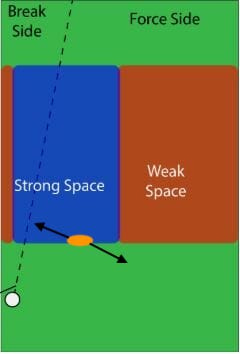

To draw on top of one of the diagrams from Joe's article, "attack from weak space into strong space" looks something like this:

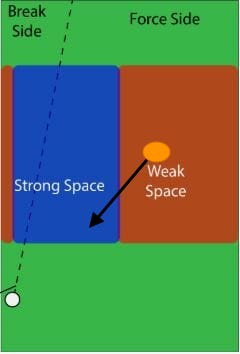

When Brown gets into "saddle point mode", their set-up looks more like this:

Not just "front of stack"

It's easy to mis-characterize this offense as "cutting from the front of the stack". But I think that prevents us from understanding what Brown's doing so well. It's clear that when the disc is near the sideline, the "front" cutter is not staying in the middle of the field, the way a stack would. As the strong space shifts closer to the sideline (see images above), the sweet spot shifts towards the sideline as well, and Brown players are clearly aware of that. For example:

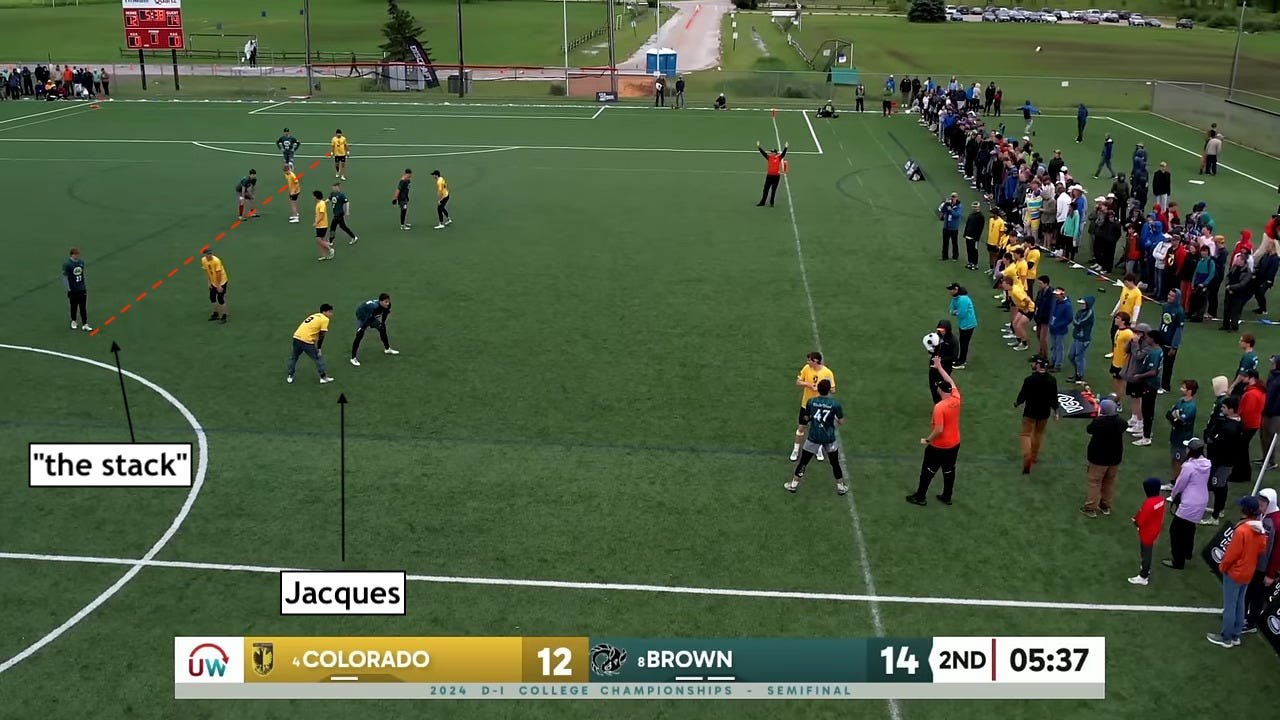

Or here’s another sequence from their semifinal against Colorado:

When the disc is initially close to the sideline, Jacques Nissen sets up off-center, much like in the image above:

But after Jacques catches a centering pass and dishes it back to Leo Gordon, Cal Nightingale's instinct is to set up with a similar offset, keeping him in the middle of the strong space, which has shifted towards the bottom sideline:

A recent Pod Practice episode highlighted what I would call a good example of a cut coming from "the front of the stack" (though in this case there isn't much of a stack to be seen):

On Joe Marmerstein's diagram, that cut might look something like this (mirrored):

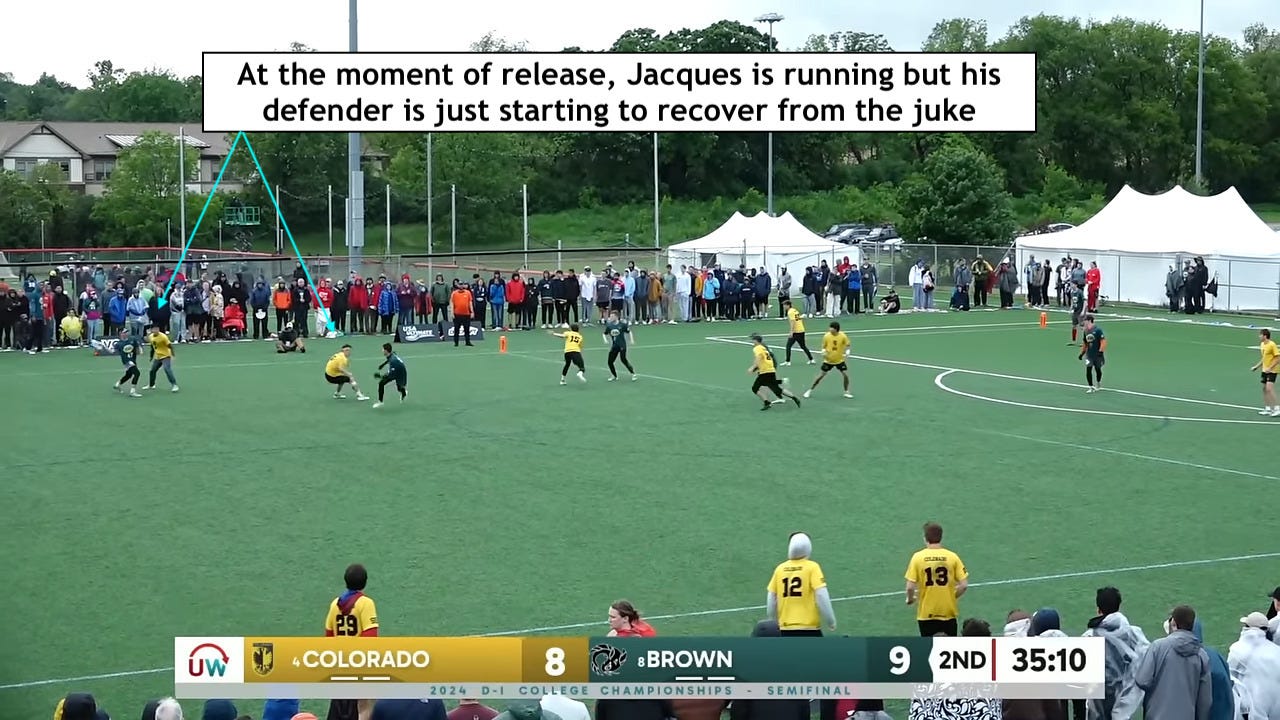

But because the cut—the commitment to acceleration—starts so far away, the defender is fully committed to spot where the disc is heading before the throw is even released:

In contrast, when Leo Gordon releases the forehand to Jacques in the clip above, Jacques is running towards where the disc is going, but his defender is still in the process of recovering from being juked:

The timing of the thrower’s throw with the cutter’s separation-generating acceleration is a big part of what makes this so hard to stop.

"Dancing in the lane"

It's been pointed out to me that San Francisco Fury doesn't do a lot of "dancing in the lane". And I, famously, am a big fan of Fury's offense. Here are a few quick thoughts about how I think about what Fury's doing vs. what Brown's doing:

When I think of the term "dancing in the lane", my main mental image is of a vert stack, with a cutter from the back faking deep, then under, then deep again, etc. I enjoy what Brown's doing a lot more than I enjoy that.

I love a flow/tempo based offense—and I've even written before (in fact, multiple times) that you should prefer zero fakes to one or two fakes—but even I can admit sometimes you just gotta be able to get open. And I think a lot of frisbee players unfortunately never learn how to actually get open. Yes, play with flow, but in those moments where you just gotta get open to save the possession, Brown shows us possibly the best way to do it:

Be a threat in multiple directions—get to a spot where that's true

Slow down, so your acceleration will mean separation

Once your first attack forces the defense's commitment, a second attack gets you open

Keep the passes short enough that defenders don’t have enough time to react to a cutter’s acceleration

In other words: timing/spacing/hard cutting is a valid way to get open. The physics that make change-of-direction are a valid way to get open, too. The ideal offense should allow space for both of those concepts at the appropriate moments. (And these concepts can harmonize, too—catch a pass in flow and the mark may not have caught up yet, meaning more viable directions the next cutter can threaten, making their fakes easier and more powerful)

And because a lot of frisbee players never learn to get open (and a lot of throwers aren't ready to hit two different looks at a moment's notice), dancing often ends up looking like a bad strategy. But when you're really good at it, it's really hard to stop.

All that being said, be careful about working this technique into your game. A team that's not wholeheartedly committed to the strategy might get upset with a player who tries "saddle point" cutting. But I think there are subtle ways to work these concepts into your game even in a more traditional offense, especially if you have one or two other teammates you spend a lot of time working together with.

Final thoughts

The saddle point concept highlights how Brown uses space differently from most teams. Brown's cutters slow down at a spot most other teams only run hard through. So many teams say things like "cut hard, clear hard". Brown's cutters, on the other hand, often spend the first second or two of their movement just moseying over to their spot. They're happy to jog right through the middle of the "strong space"—until they find that point where they're a true threat in both directions.

From that spot, they take advantage of the physics of change-of-direction and the biology of human reaction time limits to get open, over and over again.

Writing this article really made it click for me that I think too many frisbee teams focus so much on "cut then clear"-ing that they never actually give their athletes the space to get open—space to force the defense to commit in one direction, then explode the other way.

It's pretty obvious that Brown cutters sometimes do things that look—at least superficially—like "clearing". The difference is in the details, in my opinion. Both in the on-field aim (clearing happens through threatening cuts) and the way it's "taught" ("cut hard that way and Jacques will throw it if you're open enough" instead of "it's not your turn anymore, so get out of the way and don't think about getting the disc")

Loved this! Which offensive shapes do you think are most conducive (or least) to saddle point cuts?

I have been trying to teach people this concept for a long time but have never found a consice way to reference it that clearly captures the nuances as well as 'saddle point'. I really like this. A lot!