Have you ever seen a thrower release a pass to one spot at the exact moment a cutter starts to cut somewhere else?

I'm guilty of throwing some of these passes. I like to play quickly, and sometimes I release passes expecting my receiver to be seeing the same cut I do—but they don't.

What kind of heuristics can we use to avoid this happening? A potential solution is having an offensive system—cutting patterns that everyone on the team knows by heart and has practiced thoroughly.

But I don't think that's feasible as your only solution. It introduces predictability that the defense can take advantage of, and requires a rigidity that doesn't allow intelligent players to use their ingenuity on the field.

A more robust solution is for the thrower and cutter to both develop a shared mental model of what makes an opportunity good or bad.

Let's look at a couple examples and try to figure out what went wrong and how we can avoid making the same mistakes:

Here's an example from the 2024 PUL season:

The thrower pivots to look at the dump cutter, and that cutter starts an upline cut just as the thrower throws a swing pass to the exact spot they're running away from.

My take: it's hard for me to put this one on the thrower. They had an angle to get the disc to an open teammate, and they threw it to the right spot.

One factor I note is the lack of nonverbal communication (from what we can see). Perhaps there were small signals that can't be seen from our wide-shot camera angle. If I was in that play, I'd be putting my right hand out behind me to show the thrower that I wanted the swing pass. Or if I wanted to work for the upline, I would give them a head nod or thumb point towards the upline space as soon as their eyes turn in my direction. To me, this is the biggest factor in what went wrong. With the cutter's defender peeking at the thrower the whole time, the cutter has the opportunity to communicate their intentions to the thrower without their defender being in on it.

Nonverbal communication is especially helpful when there might be ambiguity in our understanding of each other's plans. I often don't need any hand signals when I cut deep. I trust the thrower sees how open I am and knows I intend to keep running deep—it's not ambiguous to either of us. But in these shorter/closer moments, there's no replacement for lots of eye contact and pointing.

Another story here is the old saying of "take what the defense gives you". The dump cutter was open for the swing pass. As the thrower's pivot starts, there's more than enough space for an easy pass into the space behind the cutter:

A cut should be a reaction to the defense—attack one space when the defense has committed too hard to stopping a pass to another space. But here, the defender hasn't made any commitment to stopping a swing pass so there's no need for the cutter to cut upline.

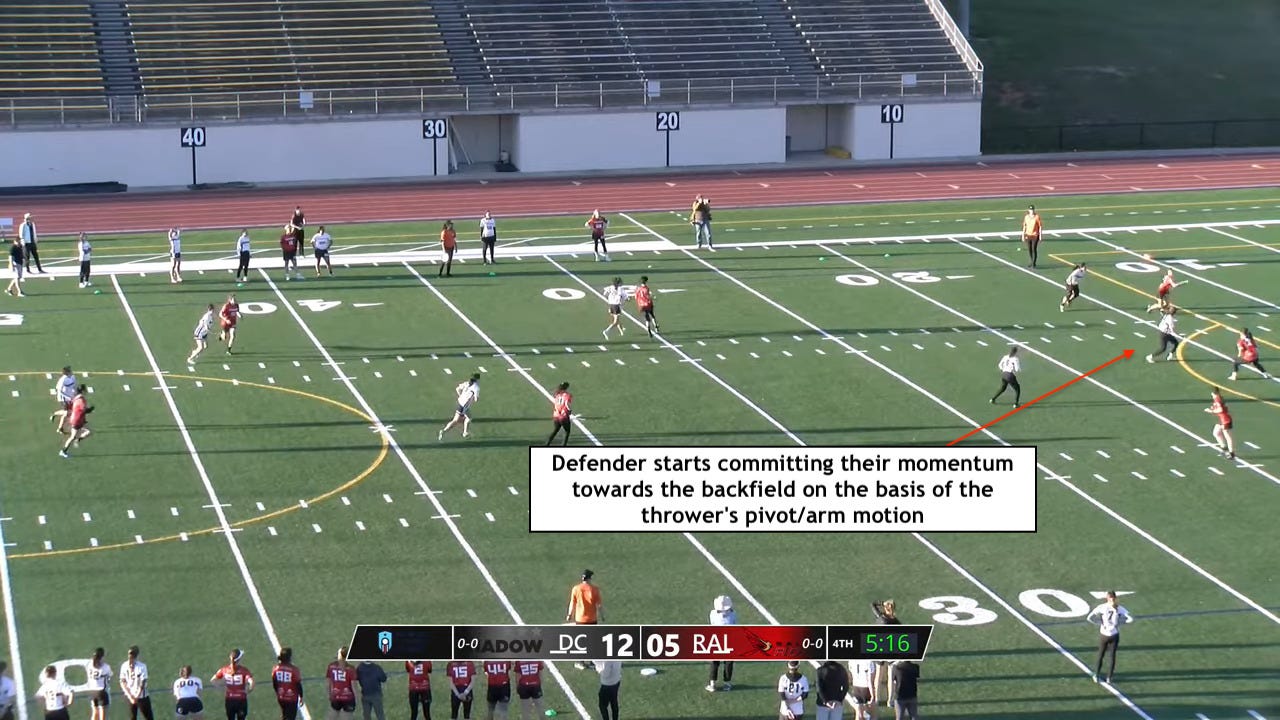

There's one thing I really do like about the cutter's motion here. They smartly predict that the defender will commit towards the dump space as the thrower pivots and starts to throw:

That idea is solid—the cutter uses their defender's knowledge of the thrower against them—but if they were committed to going upline, they needed to either have better nonverbal communication (as mentioned above) or start their cut just a tiny bit earlier.

If there's some small thing the thrower could have done better here, it's that I think they had *some* opportunity to pull out of the swing pass at the last moment. Although the cutter hadn't left their spot before the time the pass was released, the weight they were putting on their back foot seems like an obvious sign they're about to explode in a new direction. Maybe the thrower had a chance to notice this cue and holster their throw at the last moment?

The next example I've found is from a 2024 game between Portland Rhino Slam! (dark jerseys) and San Francisco Revolver (white jerseys):

What can we say about this one? A few thoughts:

Be careful bailing out of viable cuts. My instinct for this clip is again that it's more on the cutter than the thrower. I think the cutter makes a questionable decision to bail out of their first cut (well, more of a "fake", perhaps it's not a long enough action to earn the term "cut") for the swing pass. The space is open, the thrower is ready and able to get the disc there, and they'll have enough separation if they continue in that direction.

Yes, the thrower perhaps commits too quickly to throwing the swing pass, but they read the play correctly—the cutter would have been open if they had continued in that direction. I can think of a few turnovers I've thrown lately that happened in situations like this. I see the cutter start a great cut, a cut that I can see is going to be successful, but then their "cut" turns out to be just a fake, and they head off in another direction and it's too late for me to avoid throwing a pass to the grass.

Be careful pretending to call for a pass. As a cutter, I love pretending to call for a pass in one spot to induce my defender to commit before I cut somewhere else. But it goes wrong for Rhino Slam! here. I stressed in my article that you want to time your fake for a moment when the thrower couldn't actually throw you that pass—you need the thrower to see you start to cut in the new direction before they release a pass.

But here, the cutter makes the fake call when the thrower already has the disc in a forehand grip ready to throw the swing pass. The thrower sees the call for the disc and releases the pass to that spot in a fraction of a second. This is probably not the right opportunity for using this specific type of subterfuge.

Use the minimum number of jukes? Fakes are important part of cutting, but are also perhaps overrated. Situations like these show one of the downsides of fakes—you can fake out your teammates, too. Don't change directions once when changing directions zero times will do (e.g. — simply calling for a throw to space away from the defense; or boxing out + accelerating). Don't change directions twice if once will do.

Splitting your attention

In my opinion, there's one final factor that's especially hard to observe on tape. That factor is the art of paying attention to both your thrower and the defender you're trying to juke at the same time. Being too focused on your thrower will make it hard to juke a defender. But it's also possible to be too focused on your defender and lose track of what the thrower is thinking. I think that happens to some extent in both of the clips above. A quick peek at the thrower mid-juke (or: immediately post-juke?) can help reduce the frequency of miscommunication.

Shared mental models

As mentioned in the introduction, I think having a shared mental model of the situation on the field is an important meta-factor in avoiding these miscommunications. You and your teammates should have a similar vision of how to play good frisbee, in all its nuances. The thrower thinks "I'll throw the swing pass if the dump defender is sagging off", and the cutter thinks "I'll stand here and catch a swing pass thrown a step behind me if my defender is sagging".

Shared mental models help a team develop chemistry/flow: both thrower and cutter should know whether the thrower can put the disc to a particular spot. Both thrower and cutter should have an opinion on whether the cutter will be open when they reach that spot.

When I throw miscommunication turnovers, it's often in a situation where we didn't see the field in the same way. I see an open space, and I see a cutter who is able to catch a pass there. They don't "feel" the same opportunity, so either they never start running when I try to "throw them open", or they fake towards that space but then abort the cut even though they'd be open and I'm willing to throw them the disc there. If we both had a more similar feel for which spaces were open, we'd have less of these miscommunications.

Obviously chatting with teammates about what the like to do and how they saw the field in certain situations helps teammates develop a shared model. Even without a conversation you can get much of the way there just by watching your teammates closely to learn their tendencies.

Final thoughts

In summary:

Express your intentions using nonverbal communication — to me, this is the #1 tip (and applies to both thrower and receiver)

Take what the defense gives you: don't leave a spot where you're open for a viable pass

(As a thrower) as much as possible, remain aware of the various signs from the cutter as long as possible (intentional communication like nods/waves, and unintentional communication like a leg loaded up to explode into a cut)

Avoid bailing out of viable cuts—make sure you're reacting to the defense

Be careful pretending to call for the disc, especially (1) when the thrower is ready to throw and (2) you're faking towards a viable space

Be thrifty with jukes

A lot of these tips come down to "feel" for the game—knowing where the open spaces are, knowing your teammates' tendencies, being able to quickly and fluidly react to defenders. Although we can put into words some of the techniques that are being used, there's no shortcut to being great at it on the field—it just takes a lot of time and game experience.

Update [2024-10-25]:

Here’s another miscommunication from Truck Stop, courtesy of Hive Ultimate:

My brief thoughts: Could use a bit more hand signals. This one also feels like the thrower was being a little bit rushed, potentially. (But as always, remember that it’s impossible to completely eradicate mistakes from your game. Truck Stop—as well as the other teams in this article—are one of the best teams in the world. Sometimes mistakes happen.)

Update [2025-11-13]:

Here’s one I noted from 2025 Nationals:

Quick thoughts:

Lisa Pitcaithley (the cutter) looks away from the disc to check the upfield space just as Manu Cardenas (thrower) decides to throw it. To be clear, it is important to look away from the disc sometimes—see Elite players looking away from the disc. Not saying it was a mistake, just describing what happened.

Although it ends up looking like Manu threw into a poach, with multiple BENT defenders there, I’m not sure Pitcaithley wouldn’t have beaten all those defenders to the spot. I’m not quite sure what made her decide to stop her cut. So, in my opinion, it partly just seems like an incorrect read.

Likewise, perhaps Manuela could have noticed at the last minute that the cutter wasn’t fully committed, and holstered her pass. It’s a bit of a “throw to space” so perhaps Manu wasn’t looking right at Pitcaithley as she was releasing the pass. (I’ve never really thought about the specifics of how that works—are people generally looking at the person they’re throwing to, even when they’re throwing a pass that leads the receiver?)

Perhaps Pitcaithley checks the blind spot a little too late, and one of the lessons here is to make that scan just a beat earlier. If you see the thrower starting a throwing motion, it’s dangerous to start your cut. (Perhaps she didn’t think Manu would go into the throwing motion so quickly after checking the disc in?).

One thing I’ve been thinking about recently is the way that using consistent communication changes how you act when the communication isn’t there. If your cutter never shows you with your hands where they want the disc, the fact they didn’t show hands on this particular pass doesn’t tell you anything about whether they’re expecting the throw or not. Pitcaithley doesn’t call for the disc, but if she never does, it’s hard for Manu to know that this time she’s less committed than usual.

But, if someone always shows you their hands when they want the disc, the time they don’t show those hands suddenly becomes a big warning signal, and you (as a thrower) are much more likely to hold onto the disc understanding they’re not fully committed. So maybe this example is not so much about what happens in this play as it is about the overall communication environment these players are collaborating in.Overall, I think this was a pretty subtle, split-second mistake that it’s hard to blame anyone too much for. An unlucky combination of Pitcaithley checking her blind spot at the wrong moment just as Manu was looking away slightly to throw pass that leads her into the space.

This was one of my all-time favorite posts of yours... and I usually love them all! I think especially when playing a less-scripted "flowy" or "hexy" style, making lots of shorter "easier" passes (instead of looking for high-risk hucks or whatever), these possible moments of thrower-receiver miscommunication are one of the biggest sources of turnovers and hence one of the most important things to figure out how to avoid. And so (for someone who likes that flowy/hexy style!) all of your advice about how to avoid them is super helpful.

I just wanted to add one thing. The "feel" thing that you mentioned several times -- which is basically about players being on the same page about reading the situation and knowing what to expect from each other -- is something that can and should be trained. Of course, it develops automatically from playing with people. You get to know each others' idiosyncrasies like when the big eyes looking that way mean "throw it there!" as opposed to "I want the defender to think I want it there so I can go the other way!", etc... But my point is just that my favorite category of training exercises -- keepaway -- are, I think, the best way to train this efficiently because it's literally just all about thrower-receiver combos reading the situation and figuring out how to complete a pass, over and over and over again.

So, yeah, your post articulated really beautifully yet another reason why I think playing keepaway is one of the most important ways for players to train.