Pretending to call for the disc

Hopefully confuse the defense, but not your thrower

I've been thinking about Hive Ultimate's video, How To Run Dominator Offense Like Ring. Jack Williams, who's narrating the video, makes a very nice cut to get open for an easy gain after the pull. Watch it here in the original game footage (skip to 46:22, the timestamped link is misbehaving for some reason):

The cut works because Jack's defender over-commits to stopping the pass to Jack at his original location. Jack notices this and accelerates upfield for an easy 15-yard gain.

But why did the defender over-commit? In his narration, he acknowledges that he's paying attention to what the defender is doing:

I'm really focused on countering the defense's momentum to try and get separation

But he gives most of the credit for generating the opportunity to the thrower. He says:

A really effective move can be something as simple as eye contact and a small pump fake to get the defense to go a certain direction...Saul's body language and pump fake here was effective at getting the defender to commit just a little too much

While I appreciate his humility, Jack should also credit his own fake for getting the defense to over-commit. What does he do? He perfectly simulates being someone who thinks they're about to catch the disc!

(Side note: I admit that this is not the best possible video to showcase this technique. The video's a bit blurry, and the camera is pointed at Jack's back. I wish I had two more examples to include in this article...but finding good examples can be hard! If you find an example of this technique in the future, please shoot me a link and I'll update the article.)

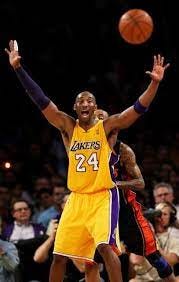

The biggest thing he does is use his hands and his eyes to pretend to call for the disc. Just in case anyone isn't familiar with this phrase, when I say calling for the disc, I mean he's doing something a bit like this (except, Jack's hands are in front of his chest instead of above him):

Or just like this (except, sorry for having yet another blurry example):

Although it's a bit blurry, I think it's pretty obvious that Jack does actually do this. Here's what he looks like as Saul is catching the pass, Jack's arms are by his side:

And just before breaking into his cut, his arms are up, calling for the disc. Zoom in on this one and it's pretty clear his left forearm is now parallel to the ground (did I just write a three-page essay about these five pixels? Sorry, not sorry.):

There are a few reasons I'm convinced that Jack's fake is the main factor in making this play. First, a good defender is not going to be just paying attention to the thrower. (And hopefully we can assume that the person guarding Jack Williams at club Nationals counts as a "good defender"!) They are obviously going to be also paying attention to the person they're guarding! If they looked at Jack and saw he was visibly interested in making a cut down the field, they would have been on alert regardless of whether the thrower was pump faking or not. For example, if he was staring downfield watching the oncoming defender, the defender definitely would've known something was up. Because he commits to the bit of "I'm just standing still, catching a pass right here", the defender is willing to commit as well.

The second reason I think Jack's fake is more important than the thrower's fake is that the timing makes more sense this way. Watch the video — Jack is already starting his cut upfield by the time the thrower is starting their pump fake. To me it seems implausible that the defender was fooled by the pump fake—the thrower had hardly done anything besides pivot towards Jack by the time Jack started cutting upfield. The defender committed before the pump fake because he saw Jack (appearing to be) committed.

This technique is an alternate version of one of my first essays, on feigning boredom. Jack shows that you can also feign being really interested in something that you're not actually interested in—the defense will react to that, too.

A personal anecdote

This technique, and this clip, leaves an impression on me because it reminds me of something from when I was much younger. When I was playing AAU basketball in high school, we had a play where my job was catch a pass from my left, and after some motion from the other players, pass it back to my left.

The first time we ran this play in a game, I got the ball and the kid to my right immediately started calling for it. It was pretty impressive—hands up, making eye contact with me, even verbally calling for it: "Hey! I'm open! I'm open!". So...I passed it to him. After the play he came up to me, frustrated: "why the heck did you pass it to me!?". I finally realized that he wasn't actually trying to get the ball from me...he was just trying to convince the defense that he was getting the ball next, so the main option to my left would be even more open.

One way to avoid situations like this is to communicate with your teammates outside of the game situation. If your thrower is aware of the way you fake, they'll have a better chance of understanding your real intentions. They'll know they need to determine for themselves whether you're really calling for the disc or just putting on a show for the defense. I made the wrong play, as a teenager, because it had never crossed my mind that my teammate might pretend to call for the ball to make the play more effective. But once my eyes were open to this as an option, I learned to better think for myself when throwing passes.

Jack Williams shows another way to avoid situations like this, and shows why he's world-class: he starts his cut at exactly the right time. It's late enough that the thrower has started their throwing motion (and the defense has badly over-committed), but it's early enough that the thrower has lots of time to react and not actually throw the disc. Arguably, Jack actually induces a believable pump fake from the thrower—because for a moment there, the thrower was actually about to pass it.

Of course Jack Williams and his teammates have developed great chemistry over the years, but this technique is achievable even for us normal humans. Even without that insane chemistry, a good cutter can still do exactly what Jack did—finding the perfect moment to cut, early enough that the thrower has ample time to stop their throw, but too late for the defender to change their momentum. I've had success using this technique when the person throwing to me was someone I had no special chemistry with. It's like a dance—if the lead partner knows exactly what they're doing, the inexperienced partner will be able to follow along smoothly.

One final note on technique: what Jack does here once again highlights how important it is for a cutter to be aware of their defender. In the video, just before Jack commits to staring at his thrower, he takes a quick glance upfield. That awareness enables this whole play—he sees where his defender is and sees how fast they're moving, and he knows what his options are.

Other faking opportunities

Jack's cut shows the most common use case for this little technique: when you (as a cutter) are more or less standing still, and the defender thinks they have an opportunity to accelerate towards you to get the block. Pretend to call for the disc, then use their momentum against them as you cut in the opposite direction.

This will often happen right after a pull, like in our example, but happens in the flow of the offense, too—especially when the defense is playing zone or defenders are playing help defense.

Another situation where I've used this technique is when I'm the first cut at the back of the stack. The defense knows I'm going to cut, so a little deception can help a lot. If they try to stand between me and the thrower to force me deep, I'll often immediately start pointing at the deep space, before the disc even comes into play. I make sure that the defender knows that me and the thrower both see how open the deep space is. This will often convince them to be a little less committed to stopping the under, giving me just enough leeway to get open for the under.

I've also used fake hand signals when I'm being faceguarded (the defender is facing me, and not looking at the thrower at all) in the dump space. I'm about even with the thrower, getting ready to make a dump cut. I'll point to the dump space, so the defender "knows" what I'm thinking. If they start making advance preparations for me to cut into the backfield, I'll use their momentum against them and explode into an upline cut.

Like we discussed above, it helps here that the defender can't see the thrower. I can make whatever hand signals I want, knowing that me and the thrower both know exactly how far away the thrower is from releasing a pass to me. The defender, staring at me, doesn't know what the thrower and I know. I can use the fake hand signal to get my defender moving, and then, like Jack Williams did, activate my real cut while it's still early enough that the thrower won't accidentally throw to the dump space where I was pointing.

Pretending to call for the disc can be an effective tool in the right circumstances, add it to your toolkit. (Unless you think this whole essay was itself a misdirection to try to convince my opponents to throw more turnovers due to miscommunications...hmmm...)

Update (2023-12-05):

In Jack Williams’ video on the upline stop-and-go/“hesitation” move, he mentions timing his cut to avoid miscommunications, as I discuss at the end of this article (He says: “I try to make this move before he’s totally committed to throwing the around”.) Watch below:

Update (2024-01-29):

The story above about my youth basketball experience involved my teammate not just calling for the ball with his hand motions, but verbally asking for it too. Here’s a great example I just found in a frisbee context. Raleigh Ring of Fire’s Alex Davis was Mic’d Up at 2023 US Nationals. In the play below, he says out loud to his thrower “I’m around, I’m around”— and then instead of getting open for the around pass, he immediately cuts deep for a score:

Obviously he’s a pretty quick guy even without using the “pretend to call for the disc” trick, but the way he verbally sets up his defender here is a perfect example of how to use this trickery to generate a little extra space. It’s curious that both of the examples of this I’ve found are Ring of Fire players!

Update (2024-04-21):

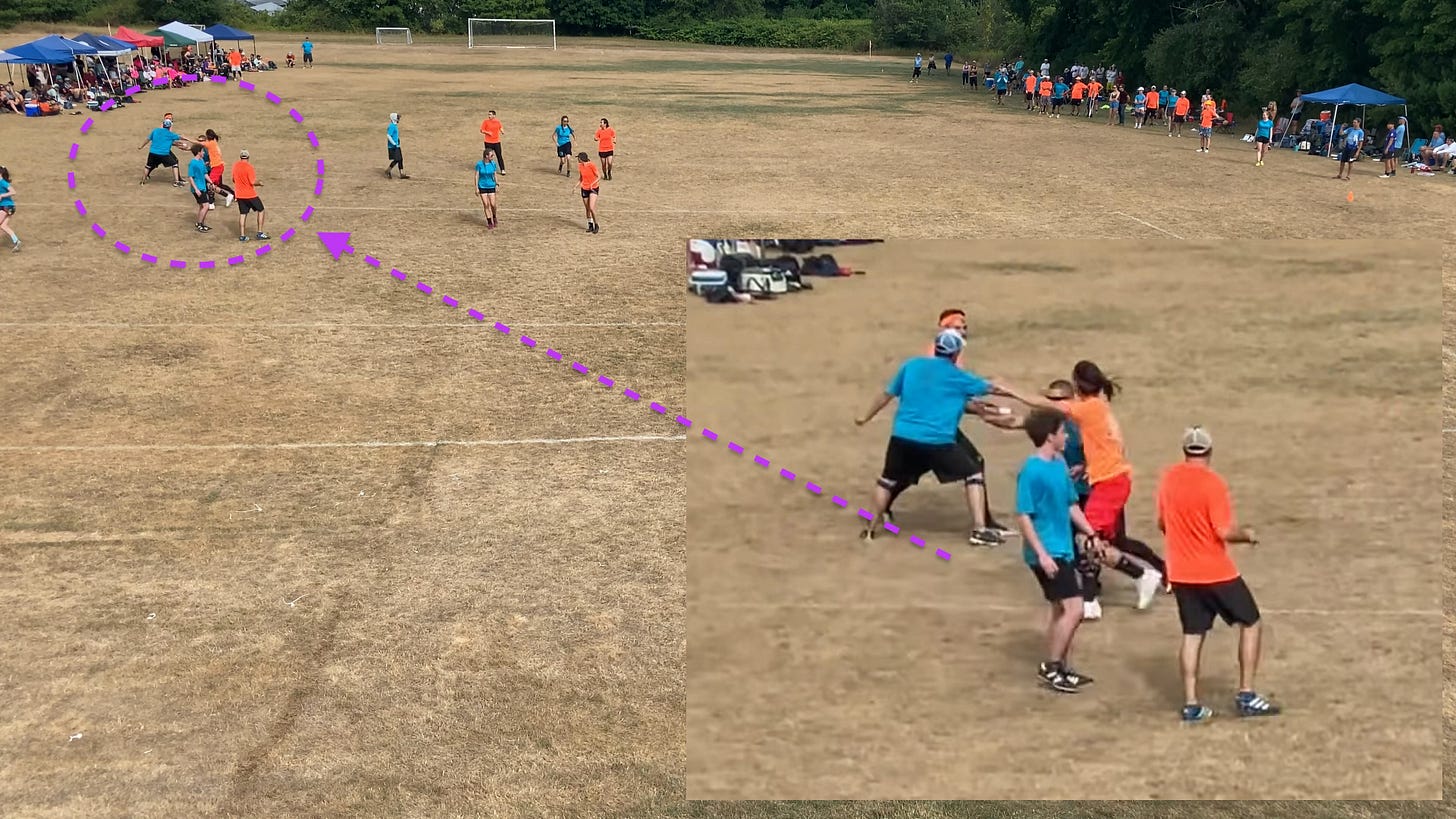

I recently learned there's actually some online film of me playing frisbee (in summer league). Watching through this old game of mine, I found a great example of me pretending to call for the disc. The clip is below (I'm in the red shorts, catching the first pass after play starts):

The camera is in a good spot to highlight what I was thinking in this moment, as it relates to the nuances discussed above:

I could see that my thrower wasn't actually at risk of releasing a pass to the wrong spot if he misread my hand signal. First of all, he's got the disc in the wrong grip. Second, he and I can both see that I'm actually pointing right at another cutter/defender pair.

I timed my hand signal to the moment when my defender is focused entirely on me. My upline cut has forced him to turn his hips and run. I can see the thrower, but he can't see the thrower at all. He doesn't have the context I (and the thrower) have to know that my fake hand signal is obviously not legitimate.

Here's a screenshot of the critical moment:

(Side note: I pivoted a few times after catching the disc—probably more than optimal—but I didn't pump fake. The weird hop when I’m catching the disc is b/c I was trying to drag my foot to stay in the endzone.)

Update (2024-05-10):

Jacques Nissen’s recent Callahan video has an interesting example of him using a similar technique to get open:

Technically, he’s not pretending to call for the disc, he’s pretending to catch the disc. But the idea behind the technique is similar and the result is just as effective so I think it deserves a place in this article. Note that, like in the example above from my game, both of these fakes are being used against faceguarding defenders.

Update (2024-10-09):

Here’s Brown’s Leo Gordon pretending to call for a pass in Brown’s 2024 College Nationals semifinal against Colorado:

[Update 2025-05-22]:

Another good one from Cole Chanler’s 2025 Callahan video (at 3:28)

[Update (2025-07-10)]:

Here’s a cool example on a stop-and-go upline cut, from an NKolakovic highlight video:

I think this one highlights how sometimes whether a hand signal is a *fake* or not depends on how the defense reacts—the cutter starts calling for the disc, but then as the defender commits towards them, the cutter reads this movement and cuts again towards the back of the endzone.

[Update (2025-08-07)]:

I really like this fake pointing by Manu Cardenas for TOKAY SuperTeam at London Invite. I’m not sure if she’s telling the thrower to pass it to her teammate that’s in that direction, or if she’s pretending to call for the disc herself in that spot, but it works! Of course note how the lightning-quick transition from pointing left to cutting right that helps make the play effective. (Rewind a bit to see the play live; I think this camera angle shows her hand motion better)