Great throwers don't pump fake

Saying what Idris Nolan probably once said somewhere

Recently, Ian French of bettereveryday coaching posted a great article on faking as a thrower, When and Why Fakes Work. It might be my favorite article of his (though, perhaps that's just a reflection of my biases given I was already interested in the same topic!). Go read it if you haven't already.

Coincidentally, I was also planning to write an article on throwing fakes. The silver lining of getting scooped is that I don't have to work quite so hard to find video clips, there are already lots of great ones in his article. There are some differences between his post and the ideas I'd like to share, so I'm still going to write up my version. Here we go.

Introduction

As Ian mentions, Great Throwers Don't Pivot is a classic ultimate frisbee essay. In the essay, author Idris Nolan says:

I’ve talked about the gratuitous faking that goes on, especially in the college and women’s game (not hating, just reporting). I don’t understand how people don’t see it. Imagine if a basketball player faked as much and pivoted a much as the average ultimate player did when they received a pass.

And in The Huddle, Issue #14: Breaking the Mark, Adam Goff, says:

Idris Nolan wrote somewhere on the Internet that he never fakes.

It's been mentioned multiple times, but I can't actually find what Idris wrote. Idris's blog, Frisbee Spew, is no longer online, but is available here through Archive.org. His comments on faking may be in there somewhere, but the Archive.org wrapper makes it frustratingly hard to search, and I gave up before finding the relevant essay.

Since Idris's article has (possibly) been lost to time, a re-write seems appropriate. Ian got the ball rolling with his article. In this essay, I'll try to say everything else that he didn't say in his post (which doesn't mean he necessarily agrees with all my opinions).

You don't have time to waste faking

Ian explains why he doesn't like faking:

The downsides to this approach are numerous but to name the major ones: you risk putting yourself off balance as well as the mark, it makes timing your throws to hit cutters significantly more difficult and it’s straight up confusing for your cutters as to what you’re actually intending to throw.

I don't really have anything to add to Ian's explanation, but I feel like it deserves more emphasis than can be provided by one long sentence. You don't have time to waste faking. In the episode of The Huddle linked above, Brett Matzuka says about pivoting:

Every time you pivot, you are...reestablishing your balance, and wasting a stall count. An average pivot takes 1 stall count to perform, so if you pivot 3 times in one possession, you only have 1-2 stall counts to look up field before you will need to dump.

The same is true of faking. Against an elite defense, you need to be able to take advantage of the smallest opportunities. Any time you're in the middle of a fake, the defense knows that this isn't the moment you're starting a real throwing motion.

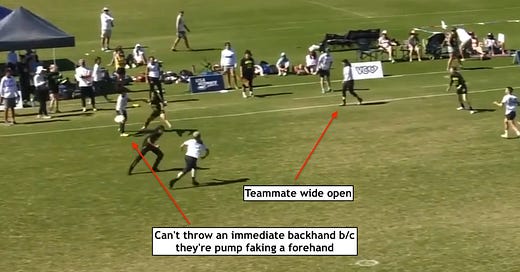

Let's take a look at two quick examples. Here's a handblock by Amy Zhou that was a recent contender for Ultiworld's 2023 Block of the Year:

The thrower has a player wide open on the backhand side, but can't immediately take advantage because they're in the middle of a forehand pump fake:

If they had kept the disc closer to their body, they would've been able to release a backhand a tiny bit quicker, which may have been enough to avoid the handblock.

Second, here's a play from last summer's WFDF U24 women's finals (USA vs. Japan).

The US handler picks up the disc after a turnover and throws a big backhand fake to nobody. At the same time, their center handler is wide open in the middle of the field—the Japanese defender is sagging off. But by the time the pump fake is done, the smart Japanese defender sees the thrower now wants to look for a dump and closes down the gap between them and the dump cutter.

Look, I don't think either of these are *perfect* examples of the point I'm trying to make. Zhou probably had a chance at the block even if the thrower didn't pump fake. The US U24 team completed their next pass up the line when the Japanese defender committed a little too hard towards the dump.

But while there are probably better examples out there somewhere, I still feel strongly that the general point is true: against elite defenses, you sometimes only have a split second to see an open receiver and throw to them. If you're in the middle of a pump fake during that split second, you may lose out on the one good opportunity you have.

Ask yourself: did it work?

Perhaps the biggest reason great throwers fake less is that it's quite obvious that many, many pump fakes don't achieve anything. For any action we engage in on the field, we should be willing to ask ourselves: what am I achieving by doing this?

Pump fakes have two obvious ways that they can, in theory, be effective:

They move the downfield defenders to help a cutter downfield become open, or,

They move the mark defender enough for you to throw around them from another angle

Take a look at the Team USA pump fake in the clip above. Did it fake out the mark? Pretty obviously not. Did it fake out the dump defender? Also obviously not. Did it fake out the defenders downfield? We can't see them on screen but it seems the answer must also be "no".

Here's another fake by Abby Hecko later in the same point:

Ask the same questions: Did it fake out anyone downfield? It seems pretty obvious it didn't. Did it fake out the mark? While they did move slightly, they still nearly handblocked the swing pass Hecko throws after pivoting around. So this pump fake didn't actually help her get more open to throw the pass she wanted to throw.

You can ask the same questions of any number of pump fakes you see in streamed games, and you'll quite often come up with the same answers: they're not achieving anything.

For elite athletes, every motion serves a purpose. There's no wasted energy. Be brutally honest with yourself about whether your pump fakes are actually serving a purpose.

Challenge your paradigm — take what the defense gives you

Faking, when done right, can be very effective at moving your mark out of the way. But stop and notice what we just said—we're faking because we're trying to throw past our mark. Assuming the same level of downfield defense (which certainly won't always be the case!), throwing past your mark is going to be higher risk than throwing somewhere your mark isn't.

The solution to our problems sometimes requires questioning our assumptions. Instead of asking "how do I fake better?", ask "how can I change things so I don't have to fake at all?"

"Taking what the defense gives you" is a common catchphrase across the sports world, and it's true here as well. Often the best way to play frisbee is to throw passes to places that your mark isn't even trying to guard. No fakes necessary.

Take, for example, this Hive Ultimate video of Potsdam Goldfingers from European Masters:

Their success comes from throwing to open players cutting in areas that the mark isn't trying to take away. There are only a few fakes in the whole video, and almost all of them are what Idris Nolan would call "gratuitous". I'm not saying that every pass will always be like this. Sometimes you'll be stuck in a tricky situation, and a fake will help you out of it.

But in general, the need to fake should make us ask ourselves: could I have done something easier? To get out of a tricky situation at stall 7, learning to throw an easier pass on stall 2 is often more effective than learning to fake better.

A fake is a hint that we're doing something hard. Often—but not always—the best solution is to do something easy instead.

Multiple commenters in The Huddle (linked above) agreed. For example, Adam Sigelman said:

When most players think about breaking the mark, they envision a thrower throwing around or over a stationary mark. However, I'd argue that the majority of break throws in high level ultimate don't happen this way. Most breaks I see are simple forehands and backhands thrown in motion with the mark trailing behind the thrower.

Faking as a signal to the cutter is so dumb

Perhaps some of you will think this is the wrong-est hot take of the article. But I feel pretty strongly about it. It's popular in ultimate frisbee culture for a thrower to use a pump fake as a signal to their cutter to clear out of the lane.

One player who sticks in my mind as an example of this is Seattle Sockeye's Simon Montague. In the clip below, he uses a big forehand fake twice in twenty seconds (there are gratuitous fakes from a number of Sockeye players on this possession):

This is a bad way to communicate with your cutters. First of all, as with fakes in general, it leaves you unable to start a real throwing motion for an extended period of time.

Second, as I've mentioned before in Think about what your opponent is thinking, a good defender will learn your signals and strategize based on them. If your huge fake is a reliable signal to your cutter, then their defender will take advantage of that information you've just given them. And if it's not really a signal to your cutter, then you need to have fakes for your fakes to keep the defense from taking advantage—the cutter will have to know those more subtle cues anyway.

Here's what you can do instead of big pump fakes to tell your cutter to clear or otherwise give them instructions:

Nod your head quickly to the side

Use your off hand

Use your voice

Use a small twitch of the disc instead of a huge, exaggerated fake

Throw a quick dump pass and then get open again

[Update (2024-09-17)]: Here’s a clip of Valeria Cardenas (one of the best players in the world). She doesn’t use any pump fakes during this stall count, but she does first beckon a teammate to come under and then points to ask a teammate to cut deep (she’s in the yellow hat, catching the first pass when the clip starts):

Finally, exaggerated fakes are unnecessary because good cutters don't need them. A good cutter will know how open they are, and will know what your tendencies are. Of course two players won't always be on the same page, but generally I don't need a thrower to signal me with a fake because I already know whether I'm open enough for their throw, and I'll clear out of my cut earlier if I'm not open. Don't insult your cutter's intelligence—they can figure out what to do without an exaggerated, time-wasting pump fake from the thrower.

You only need a shimmy

Most of the time, if you do fake, you should only need the smallest motion to get the defender moving. This is the main thrust of Ian's article and I can't say it any better than he already did. Go read his article if you want to hear more.

Work on your release speed

In a previous post about cutting, You can only fake at your defender's speed, I pointed out how the most effective technique against an under-committed defender is to simply blow past them. Make them scared of your speed, until they're willing to over-commit at the slightest twitch of your body.

The same is true of throwing. Most of the time, all you really need to get your throws off is a fast release. Optimize your release speed first. Only once you've maximized your release speed do you need to think about fakes. When you practice throwing, build up your release speed by practicing with an uncomfortably fast throwing motion. Most of us could do that for years before optimizing our release speed.

Most fakes are unnecessary because most defenders are too slow to react to the pivot speed/release speed you can develop if you really work at it.

Fake with your eyes and body

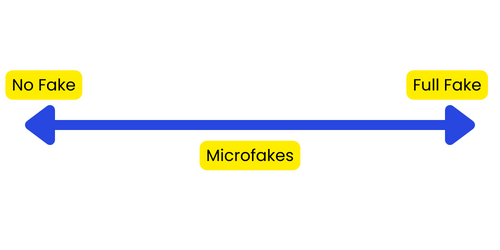

In his article, Ian suggests a spectrum running from "no fake at all" to a "full fake", with "microfakes" in between:

To put it another way, the amount of fake is the amount of your throwing motion that you go through. But what happens before you even start your throwing motion? You almost certainly look at your target. A good mark will be watching your eyes, and will try to make it harder for you to throw to the spot where you're looking.

The solution, as I've written in You, too can look off defenders and elsewhere, is to not stare down your target. Learn to watch cutters out of the corner of your eye, and learn to use your eyes to deceive your mark.

I almost never pump fake, but I almost always make it hard on my mark by not staring down my target. I look downfield when I'm getting ready to throw a dump. I look to the breakside when I'm getting ready to throw to the open side. I look at the dump to move the marker enough to get off a breakside throw.

The ~6 inches the marker moves as a reaction to the throw they think you're looking for is as much space as you'll generate on the best of your fakes. Here's a diagram that I used in my article on looking off defenders:

This technique is also mentioned in The Huddle issue on breaking the mark. For example, Lindsey Hack says:

To break the mark, I typically like to convince, or deceive, the mark that I am going to throw a different throw than what I want.

For example, if I am being forced flick and I want to throw the around backhand break, I will get into a very threatening inside out forehand flick position. Since my break flick gets released pretty close to my knees, or the ground, and is on the right side of my body, typically the mark will start to lean over towards that position. Once I have noticed that they have committed their center of gravity to defending the break flick, I will immediately pivot over to my backhand side and complete the throw.

The way you use your eyes is important, but the way you position your body is too, of course. If you purely turn your head to look at the dump space while your whole body is facing downfield, the mark won't be deceived. A common piece of advice is to face the mark. For example, here's what VY Chow said in The Huddle:

When a thrower close to the sideline stands with her bum to the sideline instead of square with the line of scrimmage, she automatically shifts the throwing lanes to facilitate an easier dump pass to get the disc off the sideline. If marker shifts position in response, the thrower now has the upper hand and is dictating what/where the throwing lanes are and where she can throw. Doing the same thing away from the sideline often produces remarkable results. If the mark is forcing one-way, the thrower should square up to the marker instead of the line of scrimmage. In doing this, the thrower has now shifted the field and created different throwing lanes - the thrower is now playing the mark more straight-up.

Another way to put it is to face as much of the field as possible. If you're in a position where you can only throw a forehand, the mark can take away your forehand without risking you throw a backhand past them. If you face a more centralized direction where you can also quickly pivot to a backhand, the mark will have to respect that.

Throw it on stall 2 where you'd throw it on stall 7

In my own playing experience and in my experience watching others, it can be especially tempting to throw pump fakes against a zone defense. Everyone wants to grab the disc and look downfield, ready to throw the perfect hammer or blade over the top. But good defenses won't let you do that. Instead, you end up wasting time staring downfield, until you throw it to the handler next to you on stall seven.

But you could've just thrown it to them on stall two! They've been open the whole time. Keeping the disc moving tires out the zone defense—mentally and physically. Disc movement constantly generates new angles for the offense to attack. Standing still with the disc throwing fakes gives the defense more time to catch their breath and get mentally caught up on the action around them.

A great example of this comes from the WFDF U24 Women's final between the United States and Japan. Watch handler Rachel Chang on the point below:

Let's look at their touches on the US possession:

1st touch (1:17:34): 4 fakes, throws a longer backhand to the sideline

2nd touch (1:17:45): 2.5 fakes, throws a 5-yard backhand to the side handler

3rd touch (1:17:56): 2 fakes, throws a 0-yard dishy to the side handler

4th touch (1:18:04): no fakes, throws a 10-yard backhand up the field

5th touch (1:18:14): 2 fakes (one of which hits the marker in the face, causing a stoppage), throws a forehand dump

6th touch (1:18:54): 2 fakes, throws a 5-yard high release backhand that's nearly blocked

[Update 2025-04-24: Funnily enough, that 5th touch mentioned above isn’t even the only example I have of someone hitting their defender in the face with a pump fake — see here.]

None of their fakes enabled them to throw a throw they wouldn't have been able to otherwise—pretty much every pass was moving the disc from the middle to the side (or back from the side to the middle) against a zone. Do the same thing without multiple fakes first, and the defense will have to work that much harder.

There were lots of superfluous fakes from team USA a whole, both on this point and throughout the game. I've been guilty of this myself, as well. But my best success against zone defenses always comes with quick, decisive passes that wear the defense out.

Final thoughts

That was a lot. Here's a summary:

Fakes take time—you can't start a real throwing motion in the middle of a big fake.

Superfluous fakes just help a zone defense slow down an offense. Resist the temptation to endlessly fake downfield and keep moving the disc quickly.

Needing to fake is a sign that you're doing something hard. Consider making easier passes instead (which will often require passing earlier in the stall count)

As Ian writes, use only the motion you need to generate separation. This is usually no more than a shimmy.

If you need to signal your cutter, there are other methods much better than an exaggerated pump fake

Using your eyes and body position to deceive the mark is often more powerful than using a faking motion.

Develop a faster release and more release angles. Why fake when you can just throw past a slower defender?

Although I titled the article in an homage to Idris's essay, I hope it's obvious that I don't think all fakes are bad. Useful throwing fakes exist. But the majority of pump fakes out there are serving no purpose, and the players using them would do well to replace them with other skills (release speed, looking off defenders, etc) that don't waste so much precious time on the field.

[Updated 2024-12-15]

Let's add another reason to avoid pump fakes:

Holding on to the disc

Every time you pump fake, there's a small—but not zero—chance that the disc will slip out of your hands while you're waving it around.

If you think I'm just making up an issue that would never actually happen, think again. It has happened, and in one of the most important games of the year.

In the 2024 US women's national semifinal between Boston Brute Squad and DC Scandal, DC had the disc a few yards away from scoring the game winning goal. A DC player caught the disc about two yards from the endzone, and used three hard pump fakes right in a row. On the third pump fake, the disc slipped out of their hands, giving Boston the disc with a chance to score and send the game to universe point.

(Thanks to Ultiworld for providing the clip.)

Boston couldn't capitalize on their chance, and after a Boston turnover DC was able to score and win the game.

I'll be the first to admit that the likelihood of this happening on any particular pump fake is extremely low. But it is a real risk, and it's one more reason to think hard about whether you really need pump fakes in your game.

I'm definitely with you on the pump fakes as a communication tool, one of my biggest pet peeves.