A few tips on cutting deep

Committing hard, committing early, sealing your defender, and more

Here are my top tips for deep cuts. This post used to be titled "A short guide to cutting deep", but it somehow kept getting longer and longer (as seems to be typical around here). If you're already an elite player there are probably no new secrets here. Just good, solid advice that will make you more effective at any level of play.

1. Fully commit

My #1 tip: commit fully to the cut, before you know whether the thrower will throw it or not.

Committing fully means maximum acceleration, right from the start. When you start a deep cut, you shouldn't be looking back at the disc for the first 8-10 steps. You should be sprinting full speed. You're not playing frisbee, you're trying to win Olympic gold in the 100 meters.

A great example of this is a cut by Philadelphia AMP's Sean Mott that I featured in an earlier article:

When Mott starts his deep cut, he breaks into an immediate sprint, and, by my count, doesn't look back at the thrower until he's taken about 8 steps. Frisbee great Jim P offers similar advice in a 10-year-old Reddit comment:

You'll sometimes see the term "head down" used to describe someone all-out sprinting. I hesitate to use that phrase because it's important to be safe and aware on the field, but assuming you've checked the space you're accelerating into, "head down" is—at least metaphorically if not literally—the level of commitment you should be going for. Sean Mott has his head down, literally:

He goes about 10 yards before looking back towards the disc:

Another good example showed up on Ultiworld just a few days ago, in an article titled Appreciating 7 Incredible Plays by the Cárdenas Sisters. #2 on their list is a deep cut by Manu Cardenas (assisted by Valeria). Manu (in the red leggings below) commits to her cut about here:

And doesn’t look back until she’s well past the half-field line:

I like to tell the players I coach:

If you commit 100% on 10 deep cuts, you might get the disc 40% of the time. But that doesn't mean that if you commit 50% you'll get the disc 20% of the time...instead, you won't get the disc at all because 50% commitment won't get you open.

(I like to think there's a life lesson here. Be vulnerable and commit to new people before you know whether they'll commit to you. Yes, you'll waste your energy sometimes, but on average you'll make lots more friends when they see how, uh, open you are.)

Committing fully also makes it possible to catch as many hucks as possible. It's counterintuitive, but running down discs that are far away from you starts before you know whether the disc will require you to run hard or not. Here's another lesson I teach (I probably took this from someone but won’t try to find a source):

Running really hard right from the start is important.

If you want to catch a disc that's as far away from you as possible, the only way to do that is by going all out, right from the very start.If you start fast and the thrower underthrows you? No problem—you can slow down.

But if you DON'T start fast, and the thrower puts the disc right at the edge of your range, you're screwed. You could've caught it if you started fast, but now it's too late—you can't run faster than your fastest to make up for taking it easy the first few steps.

For cutters who haven't already mastered this concept, this tip is so important that it could probably be the whole article. Once you're an expert at full commitment, here are a few more nuances to step up your game:

Update [2024-10-25]:

Here is another great example of Boston Brute Squad’s Floor Keulartz committing hard to a deep cut. You can clearly see how many strides she takes before turning her head back to find the disc. (She also commits to the cut before the thrower has caught the disc—see #2 below—or, at least before the thrower has turned to look downfield.)

2. Cut before your thrower catches it

In my opinion, the best deep cuts start before your thrower has even caught the disc (click the link to read my full article). There's two reasons for this:

The easiest time for your thrower to get a huck off is before the mark is set. They'll often have a 1-2 second window after catching the disc where they can huck relatively easily. After that, it can be much more of a challenge to throw a huck while being marked closely. (Plus, if they caught the disc moving forward they have extra momentum.)

Your defender is going to be the least focused on you when a disc is in the air—it's human instinct to engage in "ball watching". But if you inhibit your instinct to ball-watch and start a cut while the disc is in the air (on its way to the person who'll be hucking to you), you'll generate tons of separation from a distracted defender.

Of course, there are nuances here. Timing the start of your cut depends on your thrower's range. With teammates who can really bomb it, I'll truly start my cut before the thrower catches the disc. With teammates who I trust to make 30-40 yard hucks but can't huck full field, I'll make a little hesitation move, and explode into my cut as they turn around so I don't overrun their range.

Timing also depends on how short the field is. If cutting early and committing fully would get you to the endzone before the disc, then of course you want to start your cut a bit later. I have this Milwaukee Monarchs clip saved as an example of a player who doesn't "fully commit" to a cut by turning their head downfield. They keep their eyes on the thrower nearly the entire cut:

But, I can't fault them because they catch the goal well into the endzone. Any further commitment and they would've run out the back of the endzone before they caught the disc. On a throw like this—a somewhat floaty, shorter (40-yard) huck where the cutter started relatively deep—you can't really cut before the thrower catches it, but for longer, higher-velocity passes it's one of my favorite tips.

These two concepts—committing fully and starting early—are, in my opinion, the biggest difference between deep cutters who are clap catching wide open goals and deep cutters who are constantly needing to battle the defense to make a contested catch (or not getting thrown to in the first place).

See also: Ultiworld's Using Timing To Create Strong Deep Looks. Unfortunately, as with many older Ultiworld articles, the GIFs are broken.

3. Know who you want to huck to you

Pretty simple: not everyone on your team will be able to huck the disc. Some players may have a huck on one side (e.g. backhand) but have much less range or confidence on the other side. Some players may be comfortable catching and hucking immediately, others may need an extra second to catch, settle, and wind up a throw without a mark. A few of your teammates will be capable of throwing big hucks from a standstill with a mark set on them.

Know your teammates and their skills. If you're aiming to "cut before the thrower catches it", you'll need to be aware of your preferred hucker, even before they have the disc. Keep an eye on them (while also keeping an eye on the deep space) so you can start your deep cut as they make a cut to get the disc.

4. Signaling

I'm a big believer that hand signals are an underrated cutting skill (See Hive Ultimate's The Secret to Belgium's Team Chemistry - Non-verbal Communication). After committing hard to that deep cut, if you manage to turn your head back to the thrower before they've released the disc, give them a quick wave/point at the spot you want them to put the disc—way out in front of you hopefully. Sometimes your signal can be as small as eye contact and a nod.

Using your hands builds common knowledge between you and your thrower. The thrower knows that you know you're open, you want the disc, and you'll stay committed to the cut. This makes a thrower much more comfortable committing to the throw.

Just don't spend too long pointing, as you need to pump your arms to run your fastest.

5. Give your thrower a spot to throw into. Run into it later.

[This section feels too long. But, it’s already written, and digital column space is infinite, so I'm just going to keep it in and encourage you to skip ahead if you start getting bored.]

How do you decide which part of the deep space to cut into? There's a popular meme in ultimate that you should generally avoid "same third hucks". I'm not much of a rule-follower, and same third hucks isn't a rule I like much, either. So let's see if I can explain how to cut deep to the right spot without simplifying it into a "rule" that's sometimes wrong. I'll put my marketing team to work figuring out a memorable catchphrase for this concept (if you've got a suggestion, let me know).

I think I'd start by claiming the following things are true:

Your thrower needs some sort of "lane" to throw into—i.e. a flight path that avoids both the marker and the downfield defenders.

It's hard to read a disc that's flying directly over your head

It's harder to run down and catch a disc that's tailing away from you than one that's bending back towards you.

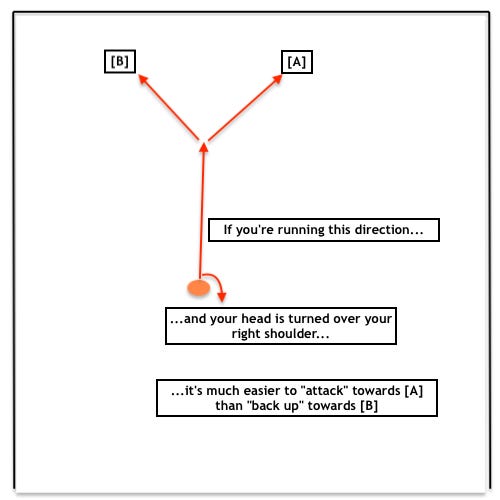

Similarly, it's easier to adjust by running "forward" to catch a disc that will land in front of you than to adjust by "backing up" to catch a disc that's on your 'back shoulder' side. ("Forward" and "backward" here are *relative to the direction your head is turned*, as in the image below).

It's possible to significantly expand the area where you can make an "easy catch" if your defender is stuck on the "wrong side" of you.

Before you know where the disc is going, you want to leave open the possibility it will go somewhere other than exactly where you expect. Cut to a spot where you retain the ability to make a play as easily as possible on a disc that's going to as many spots as possible.

In other words, a well-placed deep cut should:

Keep the defender sealed off from as much as the field as possible, for as long as possible (at least until you have a good idea where the disc is going)

Cut to a spot where the disc will curl back to you (without passing all the way across over your head!) on its way down.

Cut at an angle where the thrower's preferred flight path isn't right over your head (with some exceptions for flat passes that will float well)

Let's look at a couple hypothetical examples.

1. A smart same third cut?

Say your thrower is up against the sideline, forced forehand, and you're a ho stack cutter on that same sideline. Additionally, let's say you know your thrower loves their inside out flick huck.

This is a hypothetical where, in my opinion, the same third rule doesn't work. (Yes, it’s sort of contrived, but the point is to show ‘same thirds’ doesn’t always work.)

Here, I’d cut straight down the sideline—even knowing my thower will probably put it towards the center of the field. If the disc curls back to the sideline, I'll still be on the "low side" of the disc for its whole flight path (it curls down towards me, as if it's rolling down a hill to me). Or if the throw lands near the center, I can attack forwards easily.

But if I cut to the center of the field, and the disc curls back towards the sideline I was on, I'll be on the "high side" and the disc feels like it's rolling down a hill away from me. With my head turned over my left shoulder, I have to 'back up' to get back to it. I want to avoid this. So, my preferred cut looks like a same third cut—though, again, I may end up adjusting towards the center of the field once I see where the disc is going to land. A diagram of this situation is below:

If I knew my thrower loved outside in hucks, I might reverse this logic, and angle my cut away from the sideline to be on the low side of a disc curling in from out of bounds (That's sort of what happens in the Arizona Lawless clip at the end of this section).

2. From the back of the stack:

Say I'm at the back of the stack in the middle of the field, with the thrower in the middle of the field as well. Because of the location of the stack, an IO flick isn't really possible. I expect the "throwing lane" to be the open side of the field. Again, cutting straight downfield makes it easy to both (a) catch discs that curl back towards the middle of the field, and, (b) accelerate towards discs that don't curl back much and stay on the open side:

Again I'm sort of suggesting a "same third" cut. All three of (1) thrower, (2) cutter and (3) possible location where the disc is caught are in the central third. But what it's really about is *leaving open as much "attackable" space as possible for your thrower to put the disc into*.

One obvious truth of the same third rule is that hucks that have a high chance of landing out of bounds are worse for the offense. A huck that misses its intended target by 10 yards and lands 5 yards out of bounds will be caught by the offense 0% of the time. A huck that misses by 10 yards but still lands in the field has at least some chance of being caught by the offense. (A similar point is made in another Ultiworld article, 5 Reasons Your Deep Game Isn’t Working.)

Joe Marmerstein makes pretty much the same points (with much better examples) in his essay, Understanding Strong & Weak Space in Horizontal Stack. He focuses more on strong/weak spaces, while I focus more on where I (as a deep cutter) want to be to catch as many discs as possible coming in at different angles (and the difficulty of running "backwards" for a disc that's curling to your back shoulder). Hopefully both of those concepts can be useful to you in different ways!

To simplify, you can usually cut deep straight down the field*. Once the throw is up, adjust early to get on the low side so you can spend the later part of the chase attacking ‘forwards’ towards the disc.

*(The main exceptions: (1) when you & the thrower are on opposite sides of the field you’ll probably want to cut towards the center so it’s a shorter throw, as Joe M points out. (2) If you’re directly downfield of the thrower and worried they might throw it right over your head, moving to the side early may be helpful for reading the disc.)

Finally, wrapped up in all of this is the question of which shoulder to turn your head over to look for the disc. Joe M. doesn't really touch on this because his article mostly assumes a defensive mark is set, making the throwing lane obvious. But lots of hucks happen right after a pass is caught—and if the mark isn't set, the huck can be a break side throw:

Generally, I know what throw I expect when I commit to my cut. Did they catch the disc on an upline cut with the defense forcing forehand? They're almost certainly throwing a forehand and I'll look over my right shoulder as I'm cutting down the middle of the field.

Or did my hucker catch a disc moving towards their backhand side on a stall-zero dish? Then I'm expecting a backhand huck, and looking over the appropriate shoulder.

Naturally, you won't always look over the correct shoulder. Sean Mott, in the first clip in this article, looks over his left shoulder but has to switch and look over his right shoulder when the huck floats towards that corner of the field. Perhaps he expected an IO flick huck over his left shoulder (the disc sails right, much more than the thrower probably intended).

So, try to make it easy on yourself by building an intuition for which shoulder to look back over. But don't worry about it too much, and develop your ability to continue tracking the disc even as you swivel your head around (an important skill in American football, as well).

[Please let me know your thoughts on this section. I wanted to say something about what I do and don't like about the "same thirds huck" rule. I've tried my best to explain those nuances but I'm not sure whether I've done a good job or not.]

Update [2024-11-14]: Here’s an example from 2024 US Nationals of a deep cut that is very “same-third”-y, but works perfectly because the thrower and cutter have a shared mental model of where the open throwing lane is (and thus, how the disc is likely to curve):

6. Try a little pre-cut positioning—seal off your defender

I featured the following video of Travis Dunn in an earlier article on setting up cuts:

Watch how he starts his deep cut by sealing off his defender. Sealing can be very effective, especially when the defense commits a little too hard to stopping shorter passes. Even if the defense isn't trying to take away the under, they'll sometimes end up slightly shallower than you purely due to laziness. Sealing them off at the perfect moment can turn their small mistake into a big one. Remember that when you seal a defender off you can accelerate, but they can't (because you have green grass in front of you, but they have you in front of them!).

The GIF below highlights the key moments:

It can often be useful to draw your defender closer to the disc before cutting deep. Whether your seal them or not, you've created more open space to run into, and the thrower doesn’t necessarily need to throw it as far (this was the first suggestion in 5 Reasons Your Deep Game Isn’t Working).

What to work on

Here's a quick checklist of skills you can work on to become a better deep cutter:

Stamina (to make a number of deep cuts throughout a game)

Top speed (to run down more discs)

Acceleration from zero (to generate separation from your defender)

Reading the disc, and...

...Boxing out/positioning once the disc is in the air (see parts one, two, and three from Understanding Ultimate)

Tracking a disc (even when you have to change which shoulder you're looking over)

Cutting to the right spot to to minimize the chance you need to make uncomfortable adjustments.

Jumping effectively while running

Positioning before your cut starts to seal off a defender trying to take away short passes

Catching

Final thoughts

To recap:

Commit fully

Cut before the catch (when appropriate)

Know who'll be hucking to you

Signal to the thrower

Have a guess what throw is coming, and cut to the "low side"

Set up by sealing off your defender, when possible.

Someone on Ultiworld once said Great Cutters Don't Fake. Personally, I think that's an exaggeration, but there's a nugget of truth there. I haven't said anything about faking because I think faking to generate deep cut opportunities is overrated (just overrated, not useless). None of the examples in this article involve fakes. You can become a very solid deep cutter purely on the basis of commitment and timing. Add in a good feel for angles and the skill to seal off your defender early, and I might even say you can be a great deep cutter without faking. More often, the deep cut itself is the fake which opens up the under space.

Obviously, the more skilled you are, the more you'll probably break these rules. In the past few years we've seen more players throwing "back shoulder" hucks—e.g., an open side OI flick that curls all the way over to land on the break side (here's an example). The good thing about a huck that lands on the break side is, of course, the that the downfield defender is on the force side. The challenge is that this throw is a bit harder for cutters to cut for because of that awkwardness of sliding to the left while looking over the right shoulder. But those elite players are very athletic and very good at reading discs so it's not too much of a challenge for them if the pass goes to a slightly more awkward spot to cut to.

Love it, thank you. Enough here for a 4-yr high school cutter’s career plan.

I’ve always assumed the “avoid same third hucks” was much more about where the thrower should be placing the disc. Is that wrong? I’ve only been around competitive ultimate for a few years now.