[Edited 2023-06-21: here’s another example from a RISE UP ultimate video on timing your deep cut—their very first piece of advice is “You want to wait for your handlers to get into a power position”. A frisbee field is big and sometimes that’s too late, as I hope the article below will convince you.]

I really enjoyed this article on timing your cuts from Joe Marmerstein's blog (I wish he had blogged more!). He talks about timing your deep cut:

So, how do you time a deep cut? Like I mentioned above, the first step is to just start making hard, sprinting deep cuts when your favorite thrower catches the disc. A lot of times, just starting from a standstill at the back of the stack and sprinting deep when a handler catches an upline cut or a cutter catches an under will give you the couple yards of separation you need.

I'd like to add one piece of nuance: he focuses on cutting 'when the disc is caught', but lots of great cuts start before the thrower catches the disc. Weirdly enough, I think that even the example video shown in his post is an example of this. I've reuploaded it to YouTube to make sure it doesn't disappear (unfortunately the video quality continues degrading):

His description of the play is:

Meanwhile, the next cutter, Peter Prial, is...pulling his defender under so that he can make a deep cut when Stubbs catches the disc.

But he doesn't start his deep cut when the guy who throws the assist catches the pass. He starts his deep cut while the disc is still in the hands of the previous thrower! Here's how I see it:

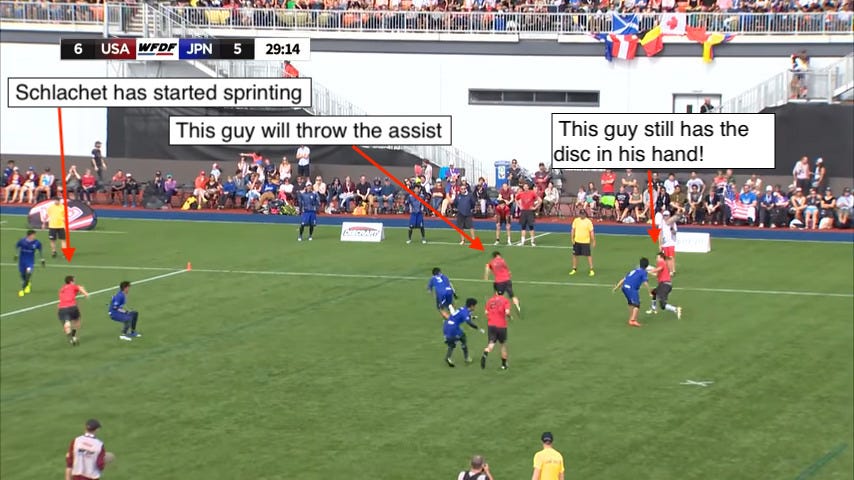

Let's look at another example. When I was thinking about this article but hadn't yet written anything down, I knew exactly whose tape to watch for an example of this type of play: Joel "somehow always open in the endzone in 2016" Schlachet. So I opened up that famous USA v. Japan WUGC gold medal game on YouTube and did, in fact, find exactly what I was looking for.

Watch the play in the clip below:

A handler makes an upline cut to get the disc, and at the same moment, Schlachet cuts hard to the front cone of the endzone and catches a goal. Schlachet has started sprinting while the disc is still in the hand of the next-to-last thrower:

Timing your cut

So if the cue for starting your cut isn't "when the thrower catches the disc", what is it?

I think great cutters are (subconsciously) asking themselves the question: where do I want to be when the thrower looks downfield? From that question, you then back-calculate when you should start cutting. A frisbee field is pretty big, so often if you want to get to that spot, you need to start running before the thrower has caught the disc. (As always, we're assuming cutters will commit hard to their cuts.)

You need to be paying attention to the primary cutter and the thrower, and be able to notice when the thrower makes the decision to pass it to the cutter. Schlachet starts his cut while the next-to-last thrower still has the disc because he has noticed that the pass is about to happen. The cues are (a) the intention he sees in the thrower's eyes and body language and (b) how open the cutter is,.

At the same time, you need to be noticing the rest of the field well enough to know where the attack-able open spaces are. At least in the examples here, that isn't too hard—in the first example it's the deep space, and in the second example, it's the 'under space', 10 yards or so in front of the thrower.

With all that information at hand, there's something like a simulation or a back-calculation going on. You know where you want to be in the future, and you need to figure out when you need to start the journey in order to get there on time. I call it a "simulation" but maybe that's making it sound harder than it really is. In reality, you experiment with this a few times, and you build up a useful intuition that informs you on when to start your cut, based on your speed and other small factors. It's not like every single cut requires you to mentally divide a distance with a velocity to calculate a time.

In other words, just leave a lot earlier on your cuts and good things will happen. Like, a lot earlier. Start here, and then experiment and adjust as needed.

I want to stress that I'm not saying you should always start your cut before the thrower has the disc. Sometimes the answer to that mental calculation will tell you to cut when the thrower catches the disc. I said don't think Joe Marmerstein's video clip exemplifies this, so here's my own example. Watch the play below, also from the 2016 USA v. Japan game:

The camera angle from behind does a great job of showcasing how the cutter starts his cut deep exactly as the thrower is catching the pass. And he timed it perfectly—catching it in the endzone for a score. There was no benefit to leaving earlier in this case, as he might have run out of space (or run past his thrower's range).

Why?

A good cut can happen at any point in the stall count, but I think there's a few reasons these early cuts work especially well.

First, it's easy for the thrower to get a throw off when the mark isn't set. This is especially true for hucks. Once the thrower has come to a stop with the disc and the defender is there marking them closely, it can be uncomfortable for all but the best throwers to get a huck off. But immediately after catching the disc, there's often a moment or two where the mark isn't set yet and the thrower can comfortably step into their throw. For that to work, the cutter needs to be in position for the thrower to put the throw up the moment they look downfield.

Second, the downfield defense will often not be ready for such an early cut. Sometimes the defender may be paying attention but just not quite mentally ready for you to start sprinting. Other times, you'll be able to catch the defense "ball watching" (as we say in sports that use balls...) It's hard not to get distracted by a disc floating through the air. But if you can train yourself to cut while the disc is in the air instead of standing there watching it fly, you'll have a big advantage over all but the most mindful defenders.

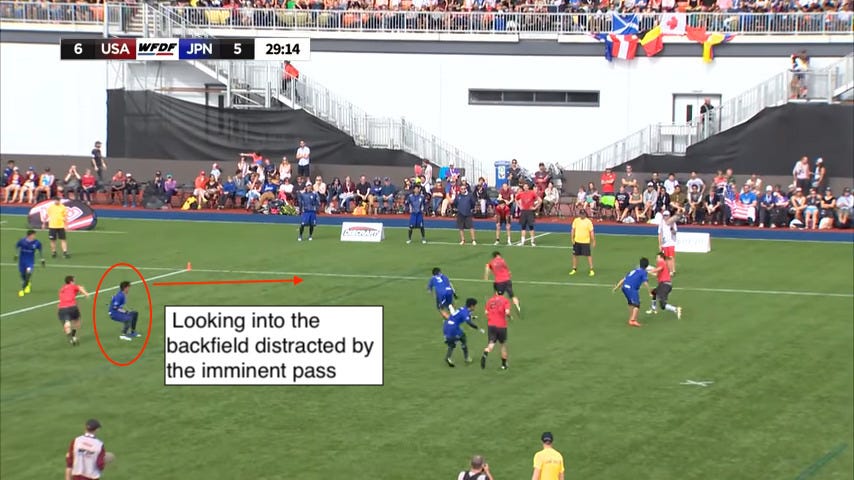

Let's go back to the screenshot of Joel Schlachet making his cut. We see that ball watching behavior from his defender — as Joel is starting his cut, his defender is (ever-so-slightly) distracted watching the pass be released. By the time that defender's attention switches back, it's already too late and Schlachet is on his way to scoring. (Note that I'm not saying it's bad for defenders to look at the thrower in general. That's something good defenders do, as I've written before. I'm just saying it's easy to get slightly distracted by a throw being released).

(A final reason for cutting early: that flow of continually making stall-zero passes is probably the most aesthetically-pleasing way to play frisbee.)

Final thoughts

Hopefully you're convinced that great cuts often start early. Figure out where you want to be when the thrower turns around and looks downfield—and understand that getting there will often require starting to sprint around the time the previous pass is released.

One more note on Joe Marmerstein's original post. He says "when your favorite thrower catches the disc"... Now, I disagree with the "when they catch the disc" part, but I wholeheartedly agree with the mention of a "favorite thrower". When you're timing these cuts, especially the deep cuts, you definitely want to be thinking about which teammate you want throwing you that deep pass. Pay a little extra attention to them, because when they get open is when you really want to start sprinting deep.

Edit (2023-08-17): In a recent video, Jack Williams points out an example where you don’t want to cut too early — you don’t want to cut so early you run out of space and end up on the sideline. I titled the article “Cut before the thrower catches it”—and while I think that’s an underappreciated technique, there’s obviously a lot of nuance in different situations, as I discuss in the “Timing your cut” section.