[Mostly touches on topics I've mentioned before, but wanted to write this down in one article for easy reference instead of having my thoughts implied and/or spread across multiple articles. I also wanted to lay out *why* it matters, and not just *what* you should be doing on pulls. This post is similar to what you'll find in Section 7.1 of The Ultimate Resource, but we take slightly different approaches and so focus on different parts of the argument.]

Many ultimate teams and ultimate players—even at the highest levels (see below)—treat receiving the pull as not that important. Offense, they seem to think, is what happens after the offense catches the pull (or picks it up off the ground), throws a centering pass, and sets up in their positions. I think this is crazy.

I've already written a few posts on fielding pulls:

Let's examine more fully why optimizing your post-pull offense matters. Here is, more or less, my thought process around post-pull offense:

I think we can all agree, the offense's job is to score. Realistically, there will always be turnovers. So we could say an offense's job is to maximize the probability they score on a particular point.

Although there's some conflicting data on this subject (see the "Appendix" at the bottom of this article), it seems pretty obvious an offense would rather be closer to the goal they're trying to score in than further away from it.

If you're trying to maximize the probability you score, you should prefer doing easy things to doing hard things. You might end up needing to do hard things, if the defense forces you to, but you should always prefer the sure thing over the risky bet.

Probably the easiest thing you'll ever do on offense is playing offense when there are no defenders nearby.

The moments after the pull is caught—for many pulls, though admittedly certainly not for all pulls—are one of the few opportunities an offense has to do easy things.

This opportunity to play easy offense can disappear entirely if a team mis-handles pulls.

One of the implications of this philosophy is that you should catch every pull you possibly can. In my opinion, it's much easier to get good at catching pulls—and then attacking immediately for an easy 15+ yards—than it is to get good at doing all the other things it takes to gain those same 15 yards on a defense that's already set up. (In other words, Be good at frisbee, not just frisbee-like things—it's not going to show up in the stat sheet that you caught a pull most other people would've let hit the ground. But it will show up in your team winning marginally more games.)

Another way of thinking about those "15 yards": if "offense" is what you do to get the disc from one goal line to the other, "handling pulls" is arguably 15/70=21% of your offense. Obviously after accounting for turnovers, etc, it's less than that...but you get the idea. If your team averages 15 turnovers per game, it could legitimately be 10% of your offense.

Aggressive pull offense can often gain even more yards than you might expect, because the more aggressively you attack the defense, the less aggressively they can run down the pull. If they come on too fast, you can use their momentum against them and run right by them, as highlighted at the beginning of Jack Williams's famous video on dominator offense. The more speed you've built up before the defense arrives, the sooner they have to slow down to keep you from blowing right past them:

I think I also focus on pulls out of principle. Attention to detail on pulls sets the tone for attention to detail in the rest of your offense. I don't trust that a team actually understands how to play offense if they don't show me they understand "gaining yards with no defensive pressure is good".

On the topic of easy-vs-hard things: I think there's also a bit of a "hero-ism" effect here. In other words, we tend to over-value when people can do hard things successfully. There's a common perception that NBA players have a high opinion of Kyrie Irving, who excels at isolation scoring. But if your goal is to win basketball games, isolation offense is just about the worst offense there is—you'd much prefer to shoot wide-open fast break layups, over and over again. Great frisbee players maximize the amount of easy things they do.

In short: easy offense is good offense. Post-pull offense is often the easiest offense you'll ever have the opportunity to play. But you have to act with urgency. Maximize the easy things you do before you start doing hard things.

Some (more) examples

One team whose (lack of) attention to pulls has disappointed me in the past, and did again this weekend when I went looking for examples, is Raleigh Radiance. Here's a pull from their most recent game against Atlanta Soul.

I don't mind at all that they didn't catch the pull, as it was too short to realistically catch, but look what happens after that. The disc comes to a stop on the turf in front of the oncoming Radiance offense:

Your eyes are not deceiving you: there literally is not a single defender visible on screen. There's no defense within, roughly, 30 yards. Guess how far they got before the defense was set up—20 yards? all 30? Nope—they made it about 5 yards before the defense got set and the offense's flow stalled (before ever really starting):

Here's another pull from the women's final at Paganello where the offense miscommunicated and didn't have anyone ready to catch the pull. Again there were no defenders even visible on screen, but the offense didn't treat that like an advantage worth being urgent about:

In this case, they were able to complete a couple quick passes anyway, but a tiny bit more pressure from the defense could’ve meant a difference of 30 yards on this play.

While Paganello is a high level tournament, I got the impression WOOP was possibly a "pick-up" team of players that don't always play together? But I don't think that makes this any more excusable. To me, that just highlights the fact that even high level players haven't fully internalized the mental processes needed to not mess up pull handling. Don't start moving forward until you're one hundred percent sure a teammate is getting in position to catch the pull. This trick works even if you've literally never played with the other handler before.

To recap, both of these examples were from games that were streamed just this past weekend—and I didn't watch either of them in full, just noticed these plays while skimming through them. It's not at all hard to find examples of offenses wasting opportunities to gain 15-20 yards or more with zero defensive pressure.

In the men's division, the pulls are, on average, longer, and the defenders are, on average, faster, so the opportunities for the offense are somewhat smaller. But it's still not very hard to find examples (see my previous article) of players not catching pulls, or teams throwing "centering passes" right into defensive pressure when there were obvious opportunities to make easy progress by moving the disc down the sideline:

As time passes and competition grows more intense, I expect more and more teams to recognize that it's malpractice to squander these opportunities for gaining easy yards.

My quick recommendations:

Catch every pull you can. Get good at catching pulls.

For pulls that you can't catch, stop them quickly and pick them up, or (for short pulls) run up to them quickly.

Don't be afraid to pick up a pull on the ground even if you're a "cutter". Immediately getting the disc moving is better offense than waiting for a "handler" to pick the disc up off the ground and make the same pass anyone else could've made.

Once you've got the disc in hand, attack. Quickly. Players who aren't catching the pull should be reading the defense while the pull is in the air so they know where the opportunities are.

Don't be afraid to attack down the sideline after the pull. Keep extra players back to offer more options than just one "centering pass" in the middle of the field.

Be ready for pulls near the sideline—get to the sideline early so you can play them in towards the middle of the field. Don't rely on hoping that a pull will land out of bounds, be in position to confirm (and to catch the disc if it's not going out).

Pulls that land barely out of bounds can sometimes be played from the sideline without taking a brick, if the defense hasn't arrived to stop you.

Know in advance the abilities of the pullers you face. Don't start jogging forward against a puller that can throw it deep into the endzone. But be ready to sprint forward against a puller who throws 40-50 yards.

Talk. Verbally verify who's catching the pull while it's in the air. If you're catching the first post-pull pass, use your voice to let the pull catcher know where you are—"you've got me here".

[Update 2025-04-23]: Wanted to add one more thought that slipped my mind in the original version of this post. I’m not *against* “pull plays”, per se. What I do think is dumb, though, is giving up free yards in order to run a pull play that’s maybe going to get you those same yards at best. First maximize the free yards, then run your pull play (if you feel the need to have one). Here’s how I put it in a previous discussion I was part of:

I think this1 matches my mental model of what pull offense "should" look like. Start with a "kick return"/aggressive attack where you get as many free yards as quickly as possible. When that slows down, the downfield cutters should be expected to be aware enough to time their activation2 to keep things going smoothly.

[Update (2025-05-22)]:

Here are a few recent post-pull moments I *do* like:

Raleigh Radiance do a good job in this 2025 game of catching this pull and making three quick passes. I would’ve preferred to see them get upfield enough to catch the pull at chest-height rather than shin-height, but aside from that I really like their aggressiveness here:

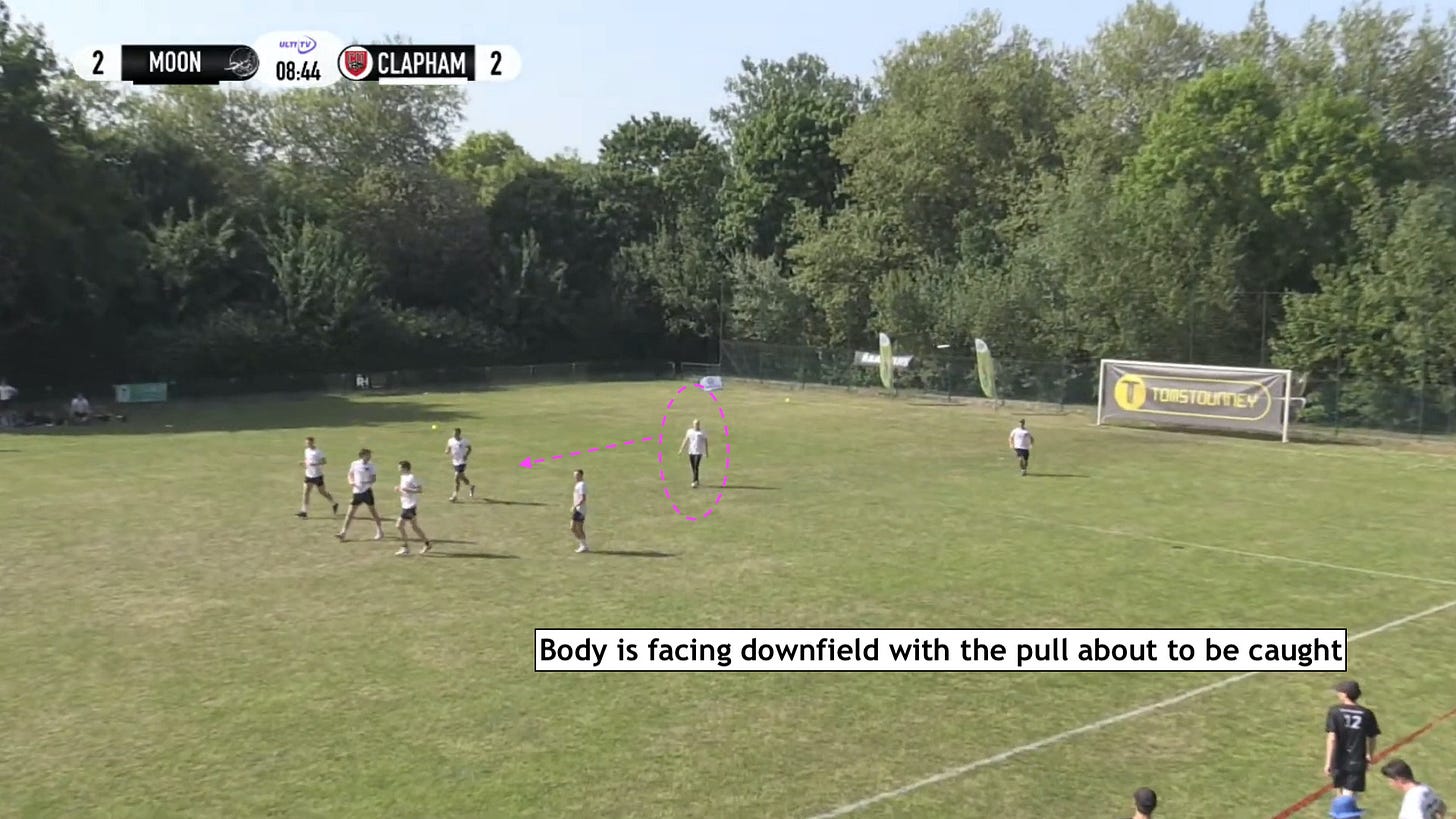

I also really like this motion from Clapham’s handler at Tom’s Tourney 2025. Instead of being satisfied to catch the disc where he is, he sees an opportunity to attack downfield and gain an extra 10 yards with no defensive pressure. I’d say this is an example of the “using the defense’s momentum against them”, as mentioned above: the one defender is sprinting right at the spot where he’s standing, and is unable to adjust in time when he breaks into a sudden sprint.

It’s also a good example, in a way, of “catching the centering pass facing forwards”—check out how he spends most of the time before the pull is caught with his body turned fully downfield, reading the defense:

Someone else’s previous comment

Both in time and in space—i.e., proactively getting further downfield as the handler dominator makes progress downfield, so they stay at the right distance to initiate their action.