Pull catching inversions

Alternate title: "Work the disc down the sideline, dang it"

(Thank you to a couple people who have discussed these ideas with me.)

High level ultimate teams are a bit too predictable in the way they handle pulls. The offense does the same thing more-or-less every time (catch the pull and throw a "centering pass" to a central handler). As a result, defenses—as we'll see below—are so keyed in on stopping that one sequence that they're vulnerable to offenses who try something different.

The biggest improvement for most teams is still to do the Valeria Cardenas-style pull catch & throw & go. Do that, whenever you can. Attack quickly before the defense arrives. But even beyond that—even when a defender runs down to stop the obvious give-and-go—there are some smaller ways for an offense to eke a little more advantage out of the first few passes after the pull.

I'll propose1 two "inversions" of the typical offense's pull handling structure that should be more popular as strategies to give offenses a slight advantage after fielding the pull. They are:

Having cutters, instead of handlers, catch the pull, and,

Working the disc down the sideline instead of centering it.

What defenses do—and why they're vulnerable

Pretty much any time you see a clip of "good pull play defense"—whether it's a crazy Callahan or just a defender who slows the offense down—you'll see a pretty standard pattern. There's 1 or 2 defenders running far ahead of their teammates—and running down the center of the field.

In Flik Ultimate's recent article on Portland Rhino Slam!'s 2024 Nationals defense, they highlight the following sequence, where a Rhino Slam! defender sprints down the field to stop PoNY's offensive progress.

Flik calls this "excellent pull coverage", but I have to disagree. This is bad offense more than good defense. Take a look at this screenshot. Is what PoNY did—centering the disc, then completing a short pass to the sideline five seconds later—really the best an offense can do in this situation?:

There's literally one defender within thirty yards, and the best strategy you can come up with is to throw the disc to exactly the one place where that defender can be most impactful?! C'mon, man.

This defense is pretty obviously exploitable, teams just need to play with flexibility instead of running the same old pull plays with their brains turned off.

This example isn't an outlier, either. Defense like this is quite common.

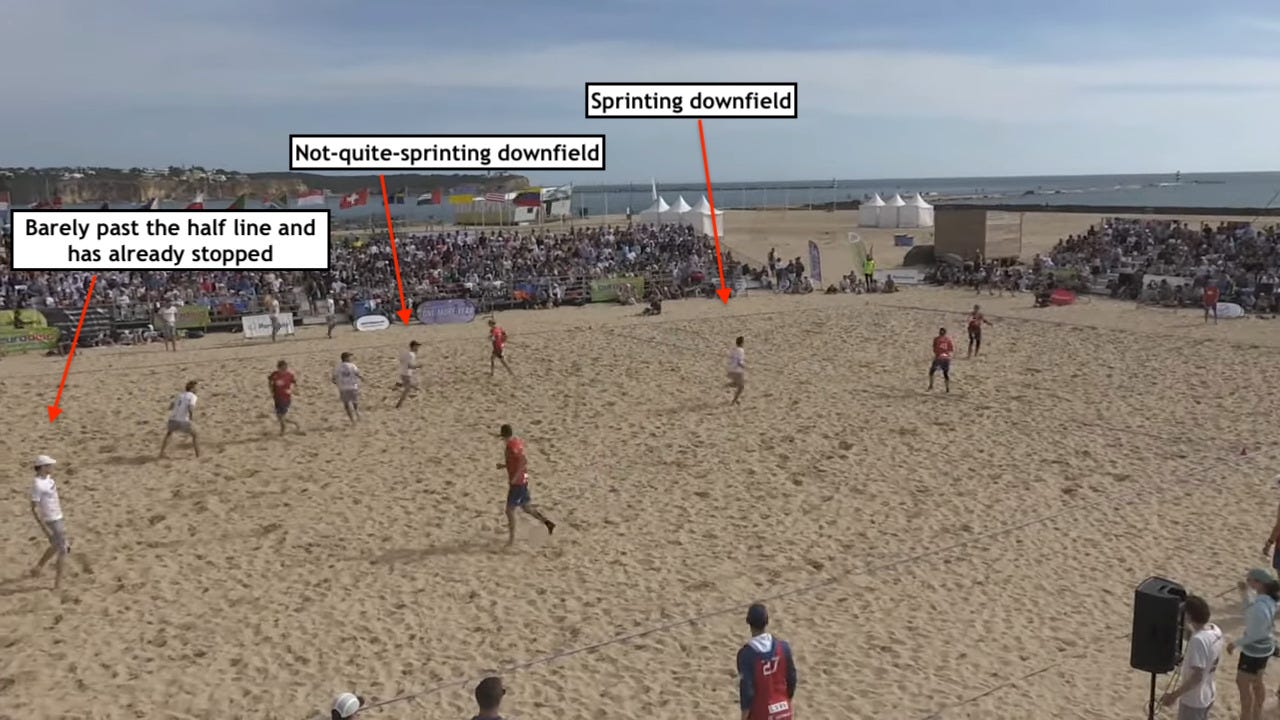

For example, here's a Callahan from a 2024 WBUCC highlights video:

Or here's a screenshot from Ultiworld's 2022 Block of the Year bracket (see Declan Kervick):

So, how to take advantage of this? I see two possible strategies. Remember the goal here isn't to switch to a new strategy that you use every single time. That would just give the defense a new predictable pattern to key in on. We want to be unpredictable and flexible—throw a curveball, so to speak—so the defense is forced to expend more mental & physical energy to slow you down.

Inversion #1: Have cutters catch pulls

Say the defense has their usual 1-2 handler defenders running to cover the pull, and we invert our pull catching team and have our cutters catch the pull. There are a few ways the defense can respond, and those responses all give our offense a slight advantage:

Option 1: handler defenders continue to sprint downfield & guard the cutters catching the pull. The defense will do a good job covering the pull, but now have suboptimal matchups, conceding a slight advantage to the offense. There’s also some marginal extra defensive confusion as the other 5 players need to determine on the fly who'll guard the handlers who've gone downfield.

(Yes, technically the offense has also maybe put themselves at a disadvantage because the disc isn't in their best thrower's hands. But if you can't trust your O-line cutters to complete a couple easy passes, you're probably not winning a championship anyway.)

Option 2: Handler defenders slow down to cover their original assignments (who aren't handling the pull). This is probably the best case for the offense: our cutter-based pull catching group should gain easy yards with a few give-and-gos until their assigned defenders speed up and reach them.

"Option" 3: Everyone sprints downfield. The first two options were strategies the defense might use if this strategy catches them by surprise. But what about once the defense knows it's a possibility? Well the obvious answer is to just have all defenders start sprinting downfield. But this is a win for the offense: the defense is forced to tire themselves out marginally more—before the actual defending even starts.

In summary, either the defense:

Gives up a matchup advantage

Gives up some easy give-and-go yards

Or wears themselves out slightly more

I've heard of teams experimenting with this inversion before, though I don't currently have any video examples.

Inversion #2: Screw the centering pass, work it down the sideline

If the defense is repeatedly running down the center of the field, maybe just...throw the disc where there's no defenders? Throwing a centering pass to the only of your 6 teammates who's being guarded is as silly as having a 2-on-1 in the endzone and attempting a pass to the person who's being covered.

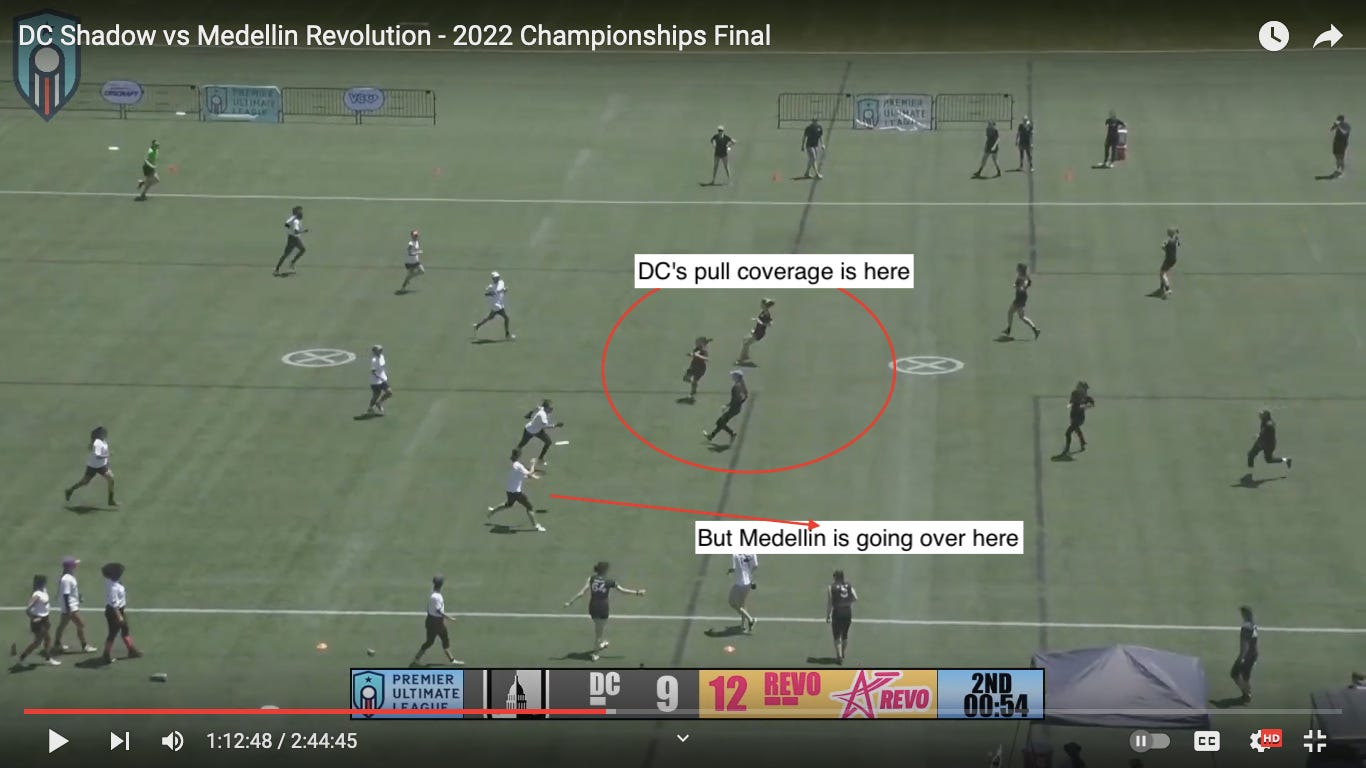

One team we've seen effectively employ this inversion is Medellin Revolution, as I highlighted in an old article:

With this strategy, I'd still have a handler standing ready to catch a "centering pass". But they’re a decoy as much as an actual option—they're there to sucker the defense into doing their usual thing, and then we'll take advantage with players spread out wide to catch a wide open non-centering-pass.

The obvious question here is whether the pros (gaining more yards & "being in flow") outweigh the cons (having the disc near the sideline). My intuition is that, on high level teams such as these, you can trust players to get the disc off the sideline consistently and so you should definitely take the free yards & flow. But I admit I don't have any conclusive data on that. Also, note that in the example from the start of the article, PoNY's next pass put them on the sideline anyways. They clearly don't mind being on the sideline, but for some reason felt the need to slow down and throw a centering pass first instead of just directly attacking down the open sidelines.

Perhaps the question of "free yards vs being near sideline" isn't really why I like the idea of working the disc down the sideline. The real reason I'm convinced this is a better strategy is that, the way PoNY did it, the offense isn't even trying to exploit the defense. Marques Brownlee is just standing there, wide open, without a defender within 20 yards of him, and neither he nor his teammates seem to think of him as an (immediate) option. He's wide open, but he has to go through the motions of running the team's "pull play" before they throw to him for a much smaller gain than they could've if they just prioritized speed, flexibility, and reacting to the defense.

So, while I don't know exactly what the data would say on yards vs sideline risk, I believe pretty strongly that actually trying your hardest to take advantage of the defense's vulnerabilities will result in better strategies than doing the same thing all the time while playing into the defense's hands and giving them time to set up.

(One little tip here: if you’re that “sideline cutter” it can be pretty effective to start jogging downfield to your “spot”, pretending you’re not thinking about getting the disc—lulling your defender into thinking they don’t have to sprint downfield. Then turn around and make yourself an option at the last moment before the pull is caught.)

Really, I think the screenshot we saw above says it all. Can you really look at this picture and not see the big opportunity the offense is missing out on?

Six seconds after after this screenshot was taken, they've still only completed one pass—which gained a measly five yards and put them all the way on the sideline. They had a four on one!!

Take what the defense is giving you, as the old saying goes. Lots of defenses—even at high levels—are giving you easy yards down the sideline after the pull2.

I had already written this article before seeing a recent Pod Practice episode featuring Hive Ultimate's Felix Shardlow. In the podcast, they discuss a few similar ideas, like:

52:20 — Felix mentions having the cutters field the pull as I suggested above (even making a little ‘inversion’ motion with his hand)

1:03:00 — Felix mentions seeing the Hong Kong open team catch the pull with 5 players back (the middle player in the Hex formation—the "hat"—would catch the pull), and only 2 players downfield

1:11:30 — Alex Atkins mentions the Summit tried having 3 or even 4 people back to catch the pull (so they could spread out evenly across the 53-yard UFA field)

Generally I like the idea of having more players back to catch the pull. As I mentioned above, it forces the defense to either run harder or give up easy give-and-gos. It also makes it easier to have more of the field covered to actually catch the pull in the first place, as Alex mentions.

Not surprising that Hive and I would have similar thoughts on this topic.

Another recent episode of Pod Practice provided a few more examples:

Later in the episode, at 42:05, Alex Atkins even points out that the guy who fields the pull “really should be looking straight down the sideline here”:

Not that I’m the first to suggest these ideas, see below

Less so in the UFA, since they aren’t pulling from the opposite goal line. But I think there’s still some small opportunities here.