I received an email from a reader shortly after I published More women throwing hammers, please!:

...I totally agree--at least the threat of a hammer absolutely would have helped Brute in that game...though my guess is Scandal would have taken their chances with that kind of game too.

My response to them was:

"I feel like there's this long-simmering discussion online between people who think the hammer (& scoober) is inherently a bad throw, and those who think if you practice it enough, it's just as viable as anything else (especially assuming not too much wind). See, for example a comment chain on this recent Hive video.

I'm definitely in the latter group. I think it's possible to be good enough at hammers that the DC Scandal coaching staff isn't dumb enough to think baiting wide open hammers is a good idea! If they're happy to concede the hammer to you, you're not good enough at hammers yet. Just my 2 cents."

In my experience, it's been drilled into people's minds that hammers are inherently bad offense. That "Scandal would have taken their chances with that kind of game"1.

The stall zero hammer specifically, in my experience, is often considered a "meme throw" that's used to represent unintelligent over-aggressiveness. And while I don't deny it's overused by bad frisbee players, good frisbee players shouldn't be deciding what is or isn't good based purely on reacting to bad frisbee players.

I think that, when thrown by good players, the stall zero hammer doesn't deserve its bad name, so here's my attempt to argue in favor of it:

The argument for stall zero hammers

1. Upside down throws are less inferior than commonly thought: To expand on the discussion mentioned above: in my opinion, upside down throws have a bad name they don't deserve. Say it with me: you are worse at your hammer than your flick because you practice your hammer 1/10th the amount you practice your flick. It's possible to throw hammers with no wobble. It's possible to throw hammers that are purposefully more floaty or more blade-y. It's possible to throw hammers into a surprising amount of upwind. But you have to actually practice. I will admit to at least one downside of the hammer—it'll always get "caught" by the wind more in a crosswind because it's being thrown more vertical. But a lot of frisbee is played in low-wind conditions. And hammers even have some benefits over rightside-up throws as well: e.g. they'll generally fall faster2 which is a positive when you need to guarantee you'll get the disc somewhere before the defense arrives.

2. The best opportunities are just after the disc moves: In line with the philosophy of point five frisbee, defenses will often be the most out of position in the moments just after the disc has moved. The more time the disc is in one spot, the more time the defense has to recover back to their optimal positioning. If the defense's suboptimal positioning leaves you with an open stall-zero backhand, you should throw the backhand, and if it leaves you with an open hammer, you should be ready to throw the hammer as well. Point-five frisbee applies to your upside-down throws, too.

3. Players are (wrongly) taught not to throw hammers. Because frisbee coaches tend to be incapable of nuance, new players are often simply told not to throw hammers. And I'm sure it's true that those players throwing hammers is a bad result for that team's offense, so the advice, on a short-term scale, isn't exactly bad.

But this is pretty bad advice for experienced players, who should be capable of understanding that they should throw hammers when throwing hammers is the best choice for their team's offensive efficiency, and not throw hammers when they aren't the best option for their team's efficiency. And because they've spent the intervening years not practicing hammers nearly enough, it's often a moot discussion anyway because they're not good enough at hammers for hammers to ever be their best option.

4. The offense-defense cat-and-mouse game: On a strategic level, a good defense will always use your tendencies against you—if they know you'll never throw an immediate hammer, they can use that knowledge to ignore cutters in the "hammer space" and make your offense 1% (or 5% or whatever the number is) harder for you. And a great offense should then counter the defense's tendencies and be willing to make the defense pay for ignoring the hammer threat. The more you can convince a defense that they have to guard you everywhere and at every moment, the easier offense will become. And because most players on most teams in today's environment aren't willing to throw immediate hammers—and defenses recognize that—they often are the most open a player can get in that space.

5. Gravity and skill development in the NBA: As late as 2010-2011, the NBA league leader in 3-pointers made less than 200 threes. In 2024-2025, 20 players made more than 200 threes. The same lessons the NBA learned apply neatly to frisbee:

Forcing the defense to guard more of the court (field) is good for the offense, and,

Players will learn new skills surprisingly quickly when they understand those skills are valuable.

3-point shooting provides "gravity" on the court, forcing defenders to guard players far from the basket. Likewise, the threat of a hammer is a source of gravity on the frisbee field, forcing defenders to respect offensive threats far from the disc, opening up space for the rest of the offense.

6. Two caveats:

To make sure it's clear: I'm not saying everyone should immediately start throwing lots of stall-zero hammers. I'm saying that you should get good enough at throwing hammers (and at hammer-related decision making) that throwing hammers is good offense for your team and then once that is true you should use that offensive weapon with confidence and with the same "point five" thought process you apply everywhere else on offense.

By "stall zero" I don't mean it should literally be your first look. A hammer across the field is probably not a better option than an open teammate right in front of you. But, like Tobias Brooks (see below), you should be able to get through that initial read fast enough that you're seeing and deciding on the hammer option by stall one or two.

For example

Two of my favorite stall zero hammers in the past few weeks are this one from the Toronto Rush's Tom Blasman...:

...and this one from U24 Team USA's Tobias Brooks (full game here, paywalled):

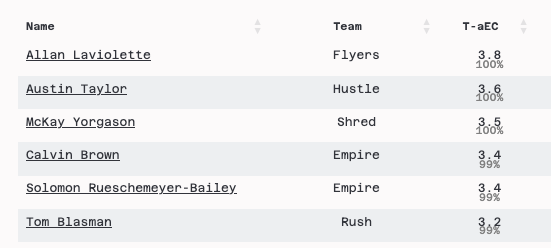

And, sure, Brooks was just named the College Offensive Player of the Year, while Blasman is one of the six-or-so most valuable throwers in the UFA, according to ShownSpace.com's model:

But, again...20 years ago people thought no one could shoot like Ray Allen, and now lots of NBA players can. And as much as we like to pretend frisbee is a sport where the "offense always scores", no UFA team this year has a red zone conversion percentage above 85%. So, roughly speaking, if you have the skills and decision making to connect on 90% of your red zone hammers, you'll be providing better red zone offense than any UFA team is currently capable of acheiving.3

Besides, if your goal is to best the best, you should copy what the best players are doing, not what the OK-est players are doing. And the best players—some of them at least—are unafraid of the stall zero hammer when it's the right choice.

I think the Tobias Brooks clip is a good example of the "cat-and-mouse" game mentioned above: the defender thinks surely I can poach in the open side here for a moment, that's how frisbee works, right?...and Brooks immediately replies no, you can't!4 In the future, a smart defense will better respect Brooks's gravity, but that's fine for the offense too, because it just makes all the open-side looks a bit easier.

The current era of the NBA is often referred to as the "pace and space" era. The stall-zero hammer is right there: space—use the whole field, including the breakside/hammer space— and, pace—do it quickly, before the defense is set.

Of course, this is all relative and my opinion is based on how open the Brute Squad players were in those specific situations. Hopefully that nuance comes off elsewhere in this article, too.

frisbees *fly*—i.e. they generate lift due to their forward motion—when thrown right side-up

Of course, this is a simplification. The hammer should be considered compared to your team's chance of scoring on that particular possession, which may be much higher than 90% depending on the current circumstances.

I also think it’s suboptimal defense: the defender of the back cutter in the stack should’ve seen the cutter clearing back towards them and orbited to the breakside to set up an impromptu bracket with their poaching teammate. But I digress.

I love this and agree 100%

Nice article - my team is beginning to realise the need for more of our better players to throws hammers, scoobers and blades as essential to our offensive development.

For a lot of lower level teams I think we get trapped because hammers are viewed in two ways:

1. The cool things that I'm going to throw just because it looks cool - My previous team had players who reversed your 1-10 practice ratio and couldn't throw a flick, barely a backhand at times, but had UFA ready hammers.

2. A scary thing only good people throw so there's no point even practicing.

Extra point, at lower levels I think something that hold hammers back is receiver ability because much like the throwing practice - people don't receive upsidedown or blady discs often enough.