Marcus tore his ACL at high school football practice in 1982. For months, Marcus mourned his college football dreams, but he emerged with a life plan that drives him still. To paraphrase the main character in Andy Weir's The Martian, Marcus resolved to science the shit out of sports injuries.

[This one's longer than a typical post, but at least it’s much shorter than you reading two full books...]

Built from Broken: A Science-Based Guide to Healing Painful Joints, Preventing Injuries, and Rebuilding Your Body, by Scott Hogan, published 2021.

Ballistic: The New Science of Injury-Free Athletic Performance, by Henry Abbott, published 2025.

Culture chronicles choose c-alliteration ... but body books bring b-alliteration.

Built from Broken is basically what you might call a "physical therapy book". Hogan explains the science behind his prescription, and then explains the exercises and exercise program. There are some anecdotes to highlight certain points, but the main focus is on the science and the exercises.

Ballistic is much more of a story. It focuses on one particular person and company—Marcus Elliott, the founder of Peak Performance Project (aka P3), a high tech physical therapy/performance training center that uses force plates, motion tracking, and machine learning models (etc) to learn how to avoid traumatic sports injuries. A few specific exercises are mentioned, and a fair bit of science is discussed, but compared to Built from Broken, there's much more story—both Marcus's background and the stories of athletes who've worked with P3.

Here's what I found interesting from each.

Built from...not that broken?

I was somewhat disappointed by Built from Broken. The Introduction made me feel like I was about to read a book written for someone like me:

The beat up aren’t quite so damaged. Yet they suffer the debilitating effects of muscle imbalances, chronic inflammation, and nagging aches and pains, all of which put a damper on exercise goals and active hobbies.

The bottlenecked are the healthiest of the bunch. Though joint dysfunction and pain don’t sideline them completely, they continually get stuck when attempting to stretch their bodies’ capabilities. Each time they progress in terms of strength, performance, or body composition, something breaks down and their bodies retrogress. Even elite athletes and professional fitness competitors suffer from this. Their limiting factor is rarely discipline or intensity or muscle-building capability or even time management. It’s almost always joint problems, injuries, and connective tissue degeneration.

No matter where you fall on this spectrum, the major impediment to realizing your physical potential and moving pain-free through life is the same: joint dysfunction. That’s the real obstacle.

But it ended up feeling more like a book meant for people who lift weights, and are "broken" from spending too much time maxing their bench press when they should be getting more variety:

...beware of favoring one body part over another. This is easy to do when you are hyperfocused on a painful problem joint. I’ve fallen prey to this more than once. After a wrist injury, I used wrist wraps while lifting weights to alleviate pain and prevent further damage. I became dependent on them. Over time, my inner elbows degenerated from picking up the slack. I was so worried about my wrists that I didn’t see the elbow injury coming. I developed tendinopathy in both elbows that would hound me on and off for over three years.

In other words, the author, as far as I can tell, was never that "broken". A torn labrum and some elbow tendinopathy. Which isn't much compared to my 3 ACLs.

Hogan's workout routine is four days a week of weight lifting complemented by biking, swimming, yoga, or tennis on the "off" days. He thinks golf is something I'll worry about causing wear and tear:

Although you will only be doing structured resistance training four days per week, this doesn’t mean you are sedentary on the other three days. Like we covered in the chapters on movement and mobility, even your “off” days from working out should be filled with varied movement.

Walking and bicycling are great ways to facilitate circulation and healing in the lower body between resistance training sessions. Swimming is a joint-friendly full-body workout and is especially beneficial for shoulder health. One or two yoga sessions per week between weight training will do wonders for recovery and mobility. Even activities like golf and tennis that you might think of as causing wear and tear can further support your fitness efforts. The opposite is also true—your efforts in the gym will enhance your performance in everyday life. They build on each other, creating a virtuous cycle that allows you to use your body to full potential.

As a result, the book didn't feel super helpful to me personally. I have no doubt that if all I wanted to do was lift weights and play pickleball, I would feel amazing about my physical health. But it's the explosive sports that have given me trouble. How do I avoid injury while trying to be an explosive athlete and also trying to get in better shape, and not "get stuck when attempting to stretch [my body's] capabilities". Though I do believe that better joint health through weight training can help me avoid injuries, I doubt it's the whole answer. Hogan never really attempts to convince the reader that his prescription works for avoiding injuries in explosive sports.

Ballistic does much better along these lines. It's undoubtedly a book about injuries that happen doing explosive movements, and how to avoid them. If I have some disappointment about Ballistic, it's that I might've hoped for more actionable advice.

But, when the thesis of the book is "we can teach you safe movements...if you come into our lab and we videotape you in slow motion and attach motion sensors all over your body while you do jumping drills on our force plates"...well, it's understandable why it's a bit light on actionable suggestions. The biggest actionable advice is go be a patient of P3—but that's not very realistic for most of us. (Which is not to say the book is completely lacking actionable advice; we'll discuss more below.)

Lift

If Built from Broken convinced me of one thing, it's that I should get back to lifting heavy weights—at least sometimes.

Load training has a unique benefit related to the regenerative processes in your muscles, joints, and virtually every cell in your body. It’s called mechanotransduction...essentially, it describes how your body turns load-bearing activity into structural changes and healing mechanisms. And its impact is proportional to the load used. The more load, the greater the response.

Studies show you must challenge your joints with weights around 80% of your one-repetition maximum to elicit the greatest adaptive response. Not only does load training build strength and muscle, it also thickens and strengthens connective tissue. For building and maintaining bone mass, studies show even heavier weights initiate the greatest bone-growth response. If you want muscles, joints, and bones that work well now and later, load training is a must.

Ballistic agrees, although its focus is always more on movements than on strength/weight lifting:

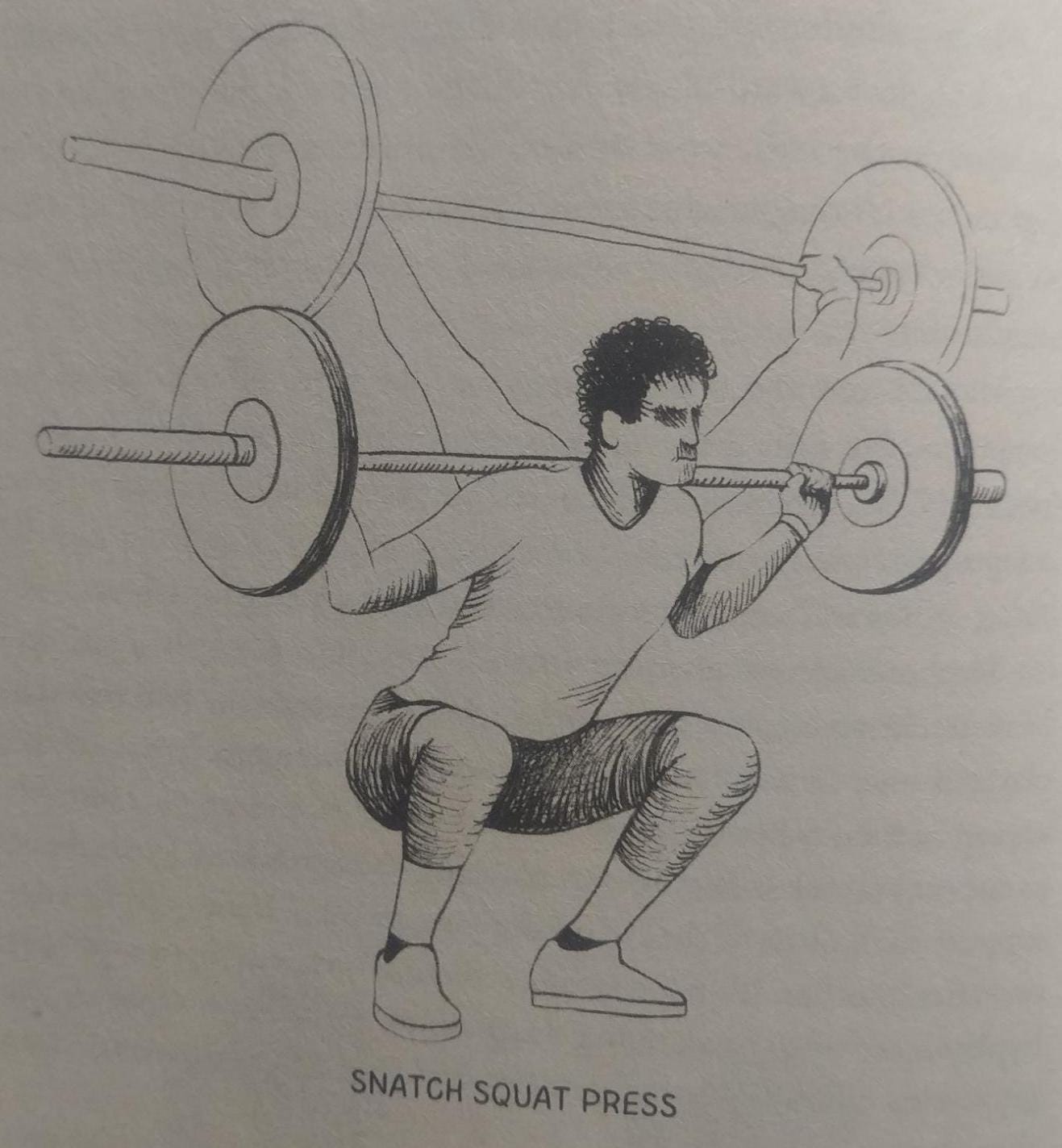

There are two main ways to lift heavy weight: with a squat or a hinge. P3 uses both, but emphasizes the hip-stabilizing hinging movements. Careless heavy lifts, the pinnacle of bro culture, can create alarming injury risk. But coached carefully, and built up over time, research shows big weights teach a body to recruit ever more surrounding tissue to support the hip's movements.

I'd gotten away from lifting heavier weights in the past few years. After reading these books, I'm starting to build back into it, although with a plan to keep it at more of a "maintenance level"—maybe once a week—instead of trying to build crazy strength.

The new standard body science

My other complaint about Built from Broken isn't really the book's fault: I didn't feel like I learned that much from it. But that’s just because there wasn't much in there that I hadn't already been exposed to, whether through other recent books like Exercised, Play On or Endure (which is also mentioned in Ballistic) or online, e.g. from Knees Over Toes Guy. (To be fair, Built from Broken was written before I'd heard of Knees Over Toes Guy! But I ended up hearing about him years before I heard about this book.)

A few examples of the modern PT/training consensus that I was already relatively aware of:

1. Injuries/decreased mobility lead to bigger injuries. Built from Broken says:

When the load is extremely far past your tendon’s load tolerance (especially if it is already weakened by degenerative changes), the tendon ruptures. This is the traumatic injury type that requires surgery or immobilization in a cast. It seems to come out of nowhere, but it usually doesn’t. It is almost always preceded by degenerative changes from inadequate adaptations to daily stressors, bad movement habits, and age. Experts estimate that up to 97% of spontaneous tendon ruptures have some amount of pre-existing tendinopathy...

...A 2016 study published in BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine found no relationship between mobility [i.e. pure flexibility] and injury risk, and that “strength asymmetry was statistically significant in predicting injury.”

Ballistic basically agrees, noting:

Over the months of this process grinding along, an NBA player tore his ACL. As is P3's custom they dove into their data to see if that player had known risk factors. He did not—but he was fresh off an ankle injury. P3 learned that, as he returned, the payer had severely reduced ankle mobility. This presented a plausible mechanism of injury: the ankle stopped absorbing much force; the knee bore the brunt.

And that's where P3 had insight the league won't get anytime soon: all-time there have been six ACL tears from NBA players who did not first demonstrate ACL risk factors in their P3 assessment. Do you know how many of those torn ACLs were in players fresh off an ankle injury? All six. Do ankle sprains elevate ACL injury risk?

2. Somewhat contrary to what we used to believe, the body does rebuild cartilage (and supplementing your diet with collagen probably helps):

In [a] study, researchers set out to measure the cell turnover rates of various connective tissues. They obtained samples from a small group of patients undergoing knee surgery and measured fractional protein synthesis rates over 24 hours. Surprisingly, they found that basal protein synthesis rates in tendons, ligaments, cartilage, and bone tissue were within the same range as skeletal muscle (1%–2% per day)...

Studies of Achilles and patellar tendinopathy show that both collagen accumulation and collagen degradation rates are increased after only four weeks of targeted load training. Collagen turnover is elevated at this point, which is a good thing because it means new cells are replacing damaged ones. However, only after 11 weeks of targeted load training does collagen degradation slow down, with collagen accumulation remaining elevated (indicating that most of the clean-up processes have finished and you are accumulating net collagen mass).

As a result, we shouldn't just build strong muscles, we can and should build strong joints, too:

We’re building bigger, stronger muscles. Faster, more powerful athletes. But we’re doing it on the scaffolding of stiff, injury-prone joint structures. We need a better way to prevent soft tissue injuries.

...Most people assume joint health is something that they gradually lose over time and there is nothing they can do about it. While age is a factor, your joints can be strengthened and fortified just like muscles...

...Also, novice athletes tend to have imbalances between the development of their muscles and tendons, with muscles being more developed and tendon health falling behind. This muscle-tendon imbalance is a major risk factor for tendinopathy.

And building strong tendons means doing slooow movements (isometrics):

Muscle responds well to a wide range of exercise modalities with an increase of strength. Tendon tissue on the other hand seems only to be responsive to high magnitude loading and repetitive loading cycles featuring long tendon strain durations…. High strain rate and frequency modes of loading as, for instance, plyometric exercise, do not seem to consistently stimulate tendon adaptation.

Ballistic basically agrees, although perhaps it's more accurate to say that Ballistic suggests training motions over training muscles:

To Marcus, merely strengthening this or that muscle makes you a great athlete about as reliably as piano scales make you Thelonius Monk. The key isn't hitting a note, it's linking together a thousand notes in thrilling ways...

Much is missing, Marcus explained, if we train just to build muscle. "When you get this thing strong," he said, pointing to his thigh, "okay, it's strong. But what's that say about how you're going to move? It doesn't. It really doesn't say much at all." Much better is to train your landings, to think about how you interact with the ground...

3. Built from Broken takes posture very seriously. There's basically a whole chapter dedicated to posture and how to improve it.

To be honest, I've basically always believed posture isn't that important. I spend a lot of time on the computer, and I don't think my posture is "good"—I slouch, and I'm pretty OK with it. The pro-slouching camp can use "trust your body" logic, too—if slouching wasn't OK, why would it be such a natural solution for my body?

If it was just Built from Broken, I'd probably happily ignore that chapter completely. But the fact that Ballistic also supports having good posture (although here it's a short section in a 250-page book) actually convinces me posture might be somewhat important:

Marcus uses the phrase computer back more often than he uses computers. He calls it the most pervasive biomechanical issue among "normies"...

Kyphosis causes practical issues...You can get away with kyphosis in straight-line sports like distance running...But it inhibits explosive lateral movement, which is key for volleyball players...

"There really is a fix," Marcus says..."My one go-to is the snatch squat press."

4. And Built from Broken advocates for one of Knees Over Toes Guy's favorite workouts:

Walking is the clearly the most underrated natural pain reliever. But in head-to-head studies, another natural pain management method was even more effective: retro walking.

Retro walking is exactly what you might have guessed—walking backward.

Backwards walking has definitely helped with the particular knee issues that I suffer from.

Toes up...

With that out of the way, let's take a look at what Ballistic has to offer for injury prevention advice.

To the extent that Ballistic has actionable advice, it's this:

...while ACLs themselves inhabit the knee's interior, the movements that doom that tissue almost al take place in adjacent joints: the hip above, and the foot and ankle below.

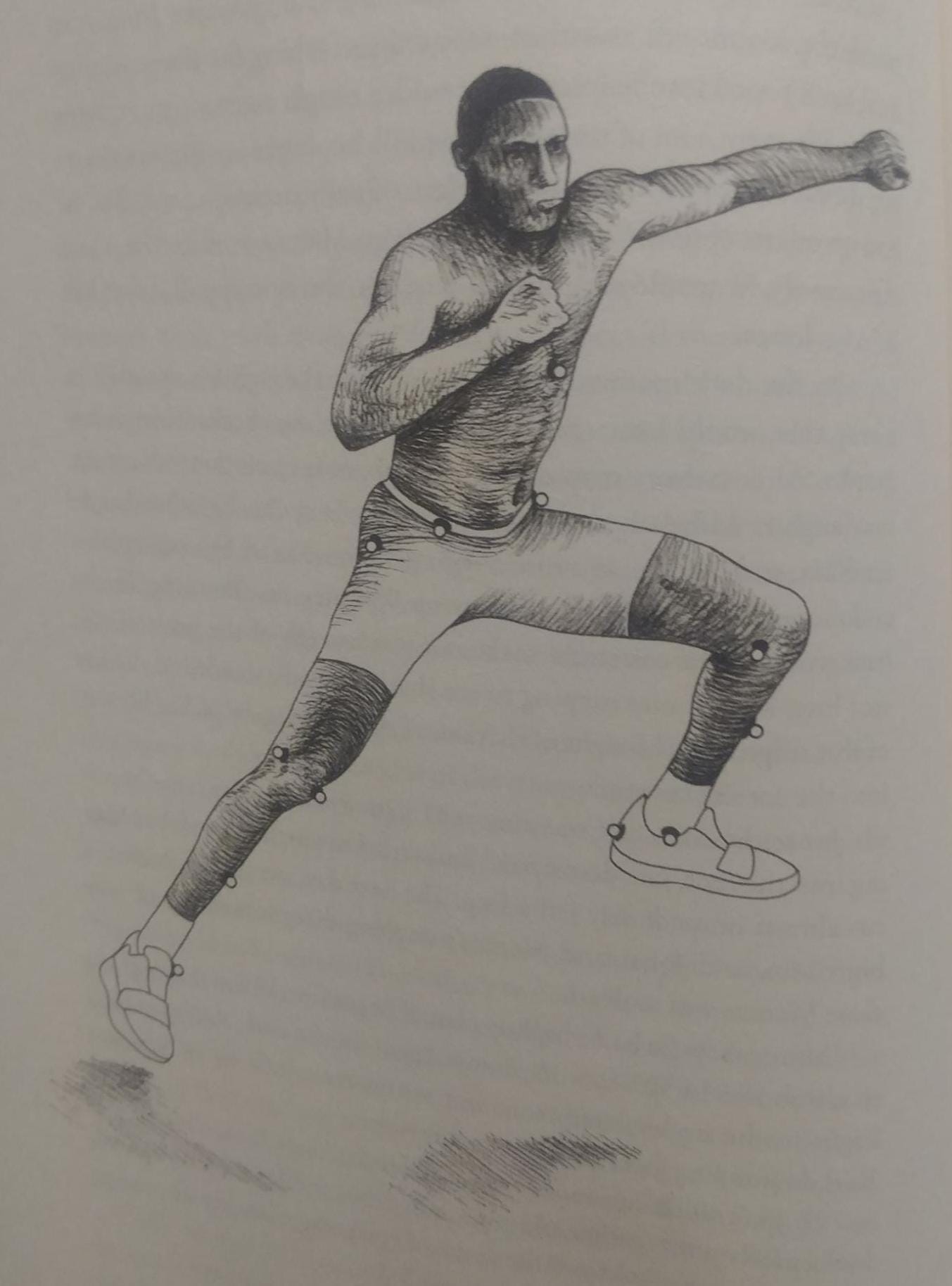

Unlucky in the middle, knees catch hell. P3 finds you can go a long way toward preventing noncontact ACL tears by strengthening the muscles of the lower leg, landing with toes up, getting hips strong and mobile, and practicing bouncy plyometric exercises...

In the game of preventing musculoskeletal injuries, the obvious early wins come from strengthening unstable hips, stretching immobile hips, and landing toes up. These are P3's biomechanical commandments. But another one is: get after it.

P3 says landing with your "toes up"1—on the balls of your feet with your ankle in dorsiflexion—is a safer way to transfer the landing forces safely into your body:

Katie had grown up playing on soft sand, and landed with her toes pointed downward. That's an absolute red flag to P3. The problem is that after the toes absorb the first little whiff of force, the middle of the foot, which is wired to some of the strongest soft tissues in the body, barely participates. Then the remainder comes crashing down on the only part of the foot that's bony, hard, and noisy: the heel. P3's biggest impact numbers always come from heels...

[Marcus] has seen people with peak landing forces of twice their body weight—and he has seen people with peak landing forces eight times their body weight. Eric says he has seen nine times body weight. With forces this large, a little technique can make a huge difference.

The trick is to get those forces passed succinctly to the Achilles tendon. We say the best jumpers have "springs". It's literally true: the Achilles is an incredible spring, which feeds up the chain through quads to hips....A lot of the exercise P3 prescribes is about positioning the foot and ankle so it's the Achilles that feels the force of the floor...

...Studies show that runners who underuse their Achilles have to do 40 percent more work.

So dorsiflexion is a main focus of P3 training:

Training dorsiflexion is both a physical and mental process...

P3 programming is inundated with toes-up moments. Marching with a plate overhead? Toes up. [etc etc]

Sometimes they quote legendary track coach Jim Deegan, who said, "Show 'em your sole," meaning lift your toes enough that people at the finish line see the bottom of your shoe.

In fact, they almost make it sound like knees are...nearly irrelevant to knee injuries:

The top fifteen factors in Eric's knee study all have to do with the hip or ankle.

As someone who's had a lot of knee injuries and has pretty much never had a hip or ankle injury, this is an appealing idea.

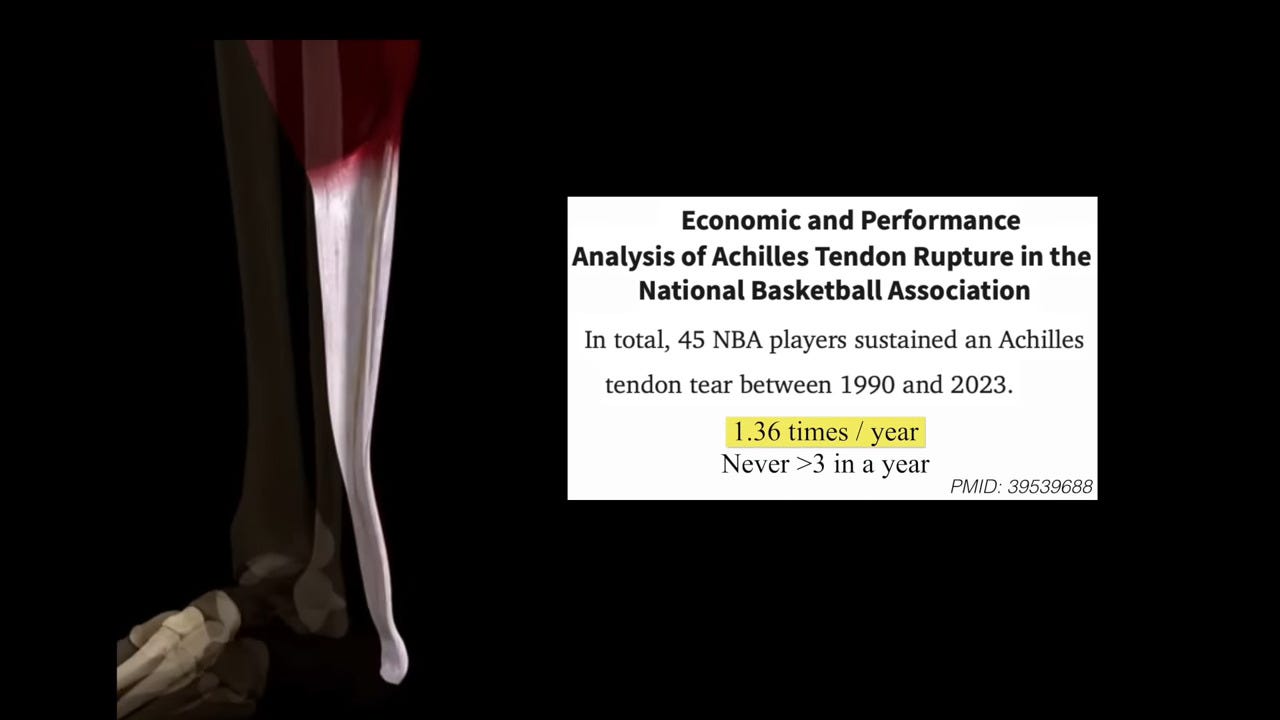

There's only one thing that has me worried. And that is—are we just going to turn ACL injuries into Achilles injuries? Even I noticed that two young NBA stars tore their Achilles in this year's playoffs. And now my YouTube algorithm is suggesting me videos with titles like Why Achilles Ruptures Are UP 400% in the NBA2 (Yes, that actually happened on a day I was writing this review.)

The linked video cites data that, between 1990 and 2023, there were never more than 3 Achilles injuries in a single year in the NBA. In the 2024-25 season, there were 8.

Yes, almost all of these injuries can be "explained"—long seasons (plus an Olympics in between), Haliburton hurting his Achilles only after a calf strain, etc—but it still should make you wonder. I am undeniably hopeful about the ideas I learned in Ballistic, but I'd definitely like to know more about what's going on with this trend of torn Achilles tendons. A quick search at the time of writing didn't return any evidence that P3 has made recent public comments about the trend of Achilles injuries.

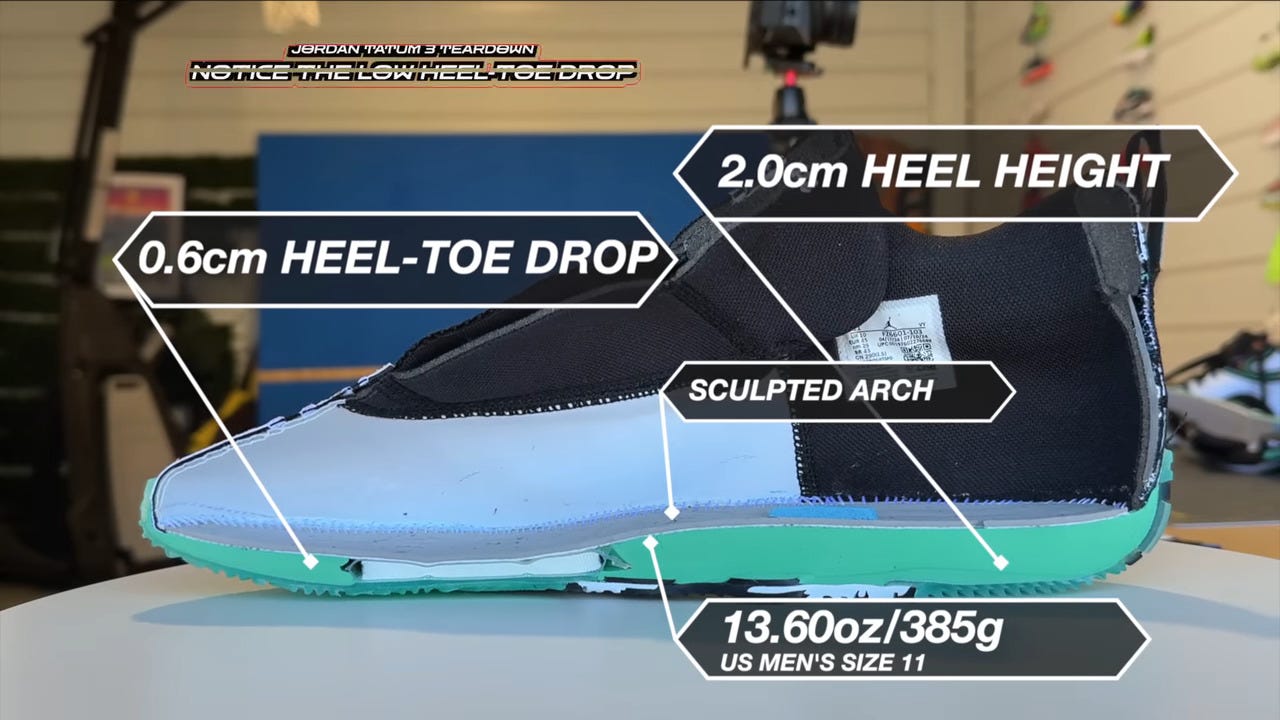

In concert with stressing the importance of loading the Achilles, Marcus Elliott believes in "zero drop" shoes—which are already somewhat popular in running, but less so for basketball.

Marcus often rants about footwear. His first concern: athletic shoes tend to have a ten-millimeter drop from heel to toe. "No one," says Marcus, annoyed, "can tell you why it's ten millimeters. There's no magic about it. Lifting somebody's heel, you affect lots of mechanics—more in crappy ways than good ways." Certain kinds of weight-lifting shoes have elevated heels to allow for deeper squats, but other than that, P3 sees no benefit to elevated heels.

In fact, they see danger. Elevated heels encourage people to land toes down. At slow speeds, that increases forces running through the knees. In big, explosive movements, that "puts their knees in a dangerous position."

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the videos on Achilles injuries linked above points out that shoes with less drop, like 6mm—which seem to have been growing more popular recently judging by these videos—put more stress on the Achilles.

The videos linked above both mention the new trend of lower drop shoes as a possible contributing factor to NBA Achilles tears.

But neither of the linked videos suggest "athletes are being taught to load their Achilles more" as a culprit in the recent trend of Achilles injuries. Almost feels like I'm doing a little investigative journalism here putting these pieces together...

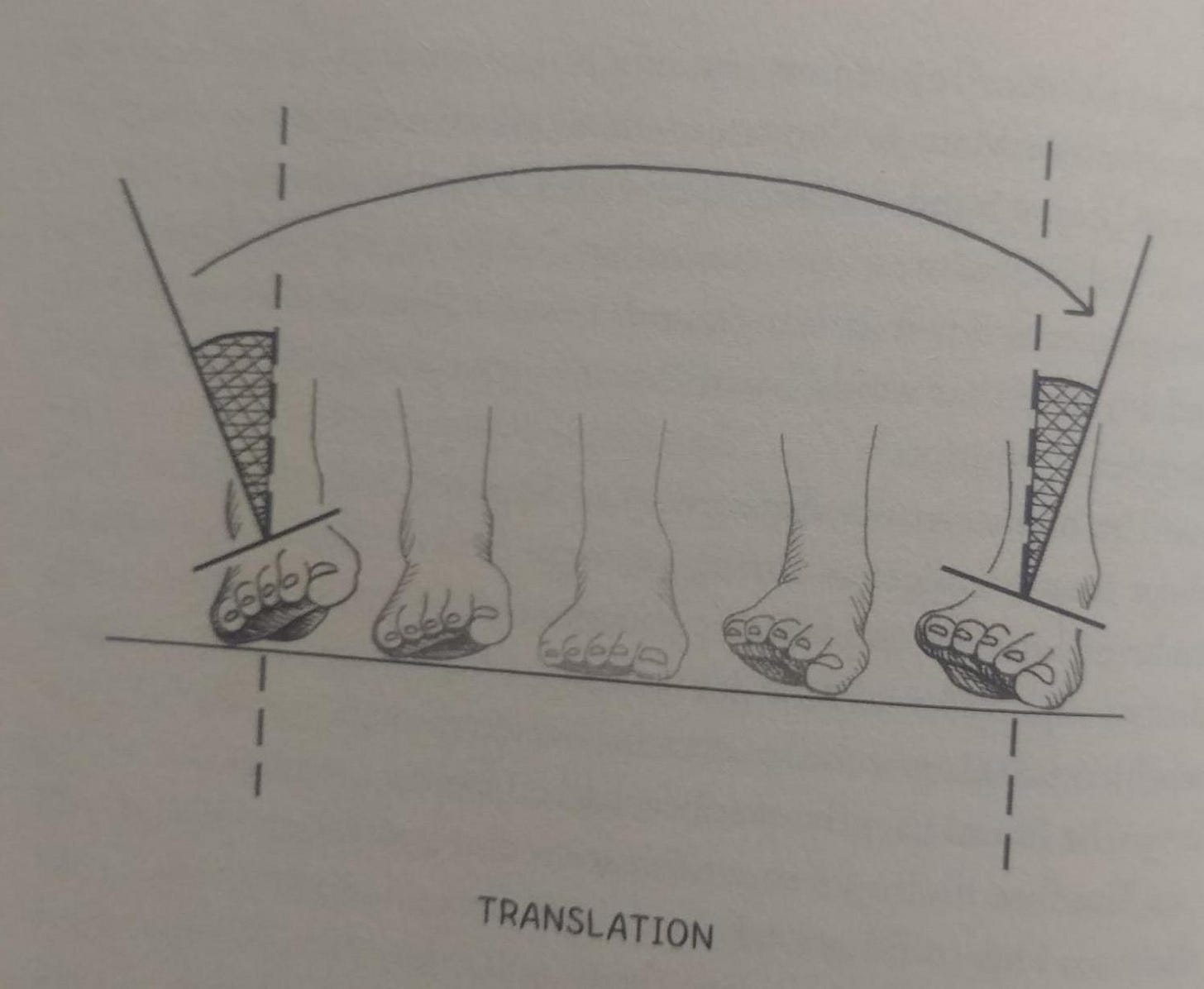

A final note on toes, feet, and knees: Ballistic reports that P3 believes something they call "translation" is an incredibly important predictor of knee injuries:

But one factor rose above all the others. Every single injury, a full 100 percent, involved something Eric named "Translation". "Nobody knows about that," says Marcus. It's a movement that hasn't been well studied, perhaps because it involves a body part seldom associated with knee injuries: the foot...

Eric plays a slow-motion animation of an NBA player's lower leg during a drop jump...The foot arrives at an odd angle, and touches down—at first, anyway—only along the outside edge. It appears innocent enough. The trouble is that by the time the foot's edge runs out of elasticity, there's much more landing yet to come. As the video rolls, so does the foot, from the outside edge, across the sole, to the inside edge, "translating" the weight. By the end, the arch is crushed, and the shin bone has swiped, like a windshield wiper, from one worrisome extreme to the other...You don't need [a biomechanics degree] to guess that, off camera, the knee is unhappy.

Some ankle roll is normal—about eighteen degrees' worth of windshield wiper-style translation is typical in NBA players....But...when translation reaches twenty-five degrees, the red light of injury risk blinks on...

The P3 staff send players off to the basketball court with all kinds of known issues, from knee pain to tight hips...But translation is different...When he's training new coaches, Jon tells them that if they see an athlete's foot striking the floor like that, even in warm-ups, "stop the workout".

...Hips strong

I have less to say about the other "easy win" in injury prevention that P3 has uncovered: strong, mobile hips. And, at least to me, it felt like less of a focus in the book, as well.

Inefficient hips are a factor in ACL injuries, but they also, according to P3, are a source of back pain:

...among NBA players, blenders [people who don't activate their hips sufficiently when landing, essentially] are 300 percent more likely than yielders [people with better landing form] to have back trouble.

...The most common advice to fix back pain is to stretch and strengthen the core...But in many of those cases, Marcus says, "that has nothing to do with it. Their cores are perfectly strong and flexible."

Instead, blenders land without the helpful control of the big muscles of the hips and posterior chain. When the hips don't sift the force of landing to the glutes, impact forces travel up into the lower back...

While Ballistic seems to suggest that there's one right way to land, P3's research found that different people have different ways of jumping:

It turned out that the prescription for a good jump was like so many prescriptions: different by patient. [Their] analysis identified three clusters, each with their own movement characteristics and recommendations.

Stiff flexors jumped without bending any joints much. They put huge forces into the ground by being quick, carrying momentum from the run-up into jumping higher...Additional movement didn't help this group of players jump higher. So for them, P3 recommended quick and snappy half squats, [to] develop more force without implementing deep knee bends that would make them slower on the ground.

Hyper flexors bent significantly through the ankles, knees, and hips...slower on the ground, and generated smaller forces—but jumped just as high as stiff flexors, thanks to the magic of the body's built-in rubber bands.

A third group, mostly among the league's tallest players, were stiff in the ankles and knees, but bent so much at the hip that their chests would often end up parallel to the floor—hip flexors. P3 recommended aggressive strength training in the posterior chain to give them increased force without having to change their mechanics.

Built from Broken, by the way, agrees with the role hips play in knee pain, pointing out:

A 2015 study published in the Journal of Athletic Training demonstrated that knee rehabilitation programs focused on hip function reduced knee pain levels faster than those focused on knee function alone.

Built from Broken also suggests a theory that your body's joints "alternate" in function between stability and mobility. It feels a little too cute to be true for me, but it's at least an interesting idea:

All joints have a stability component and a mobility component, but each joint tends to favor one or the other preferably. This is known as the joint by joint concept. Here’s how the kinetic chain of joints in your body is set up from your feet to your shoulders. Notice how the primary function alternates between stability and mobility as you move up the chain:

Feet: stability

Ankles: mobility

Knees: stability

Hips: mobility

Lumbar spine (low back): stability

Thoracic spine (upper back): mobility

Scapulothoracic (scapula): stability

Glenohumeral (shoulder): mobility

So while strong hips have their place next to "toes up" on P3's core commandments, I felt like I learned less about the hips than I did about the feet/achilles. What does it look like when the hips aren't activated? What are the cues—the equivalent of "toes up"—to better activate your hips? "Femoral rotation" is mentioned as an injury risk, but for me at least, it's not as intuitive to understand—and to understand how strong hips help prevent it—as the feet/Achilles are.

Ballistic sort of recognizes this, saying "the rest of us [non-experts] are generally hip-illiterate" and "We're trying to fix problems that are largely invisible"—but also quotes a P3 trainer saying "Athletics is hip extension". Going back through the book, perhaps this is their most concrete advice on hips:

Essentially, every person who has ever been assessed at P3 has a primary target to work either on hip mobility or stability—seldom is it neither, occasionally it's both. Marcus thinks it's within your powers to divine which club you are in...

P3, KOTG, and me

As mentioned above (and in previous posts), I've followed the Knees Over Toes Guy (KOTG) online and have used—and continue to use—some of his exercises.

There's an interesting tension between P3's thesis—that knee injuries are mostly about the hips and ankles— and KOTG's thesis—that you can bulletproof your knees by making your knees strong.

I think the KOTG exercises have absolutely helped my knees feel better than they've felt in a long while—I've improved both my strength and my mobility/flexibility. And while I like the idea of avoiding injury by making my knees stronger, there's also a lot of appeal to the possibility of reducing injury by learning to send less stressful forces through my knees.

But everyone, Ballistic included, agrees that injury/weakness leads to more injury. So maybe for me, KOTG exercises are an important part of rebuilding my knee strength and mobility after multiple surgeries when I was younger. But people who already have strong, functional knees may benefit more from learning the Ballistic movement patterns that don't overstress their knees.

As a young athlete, I think we all knew that landing on your heels was bad. But I don’t remember ever learning that there was a difference between “toes down” (landing a bit further forward, on your toes) and “toes up” (landing just a bit further back, on the balls of the feet). It wouldn’t surprise me if this was one factor in my ACL tears. It’s possible someone taught me to land on the balls of my feet and I misinterpreted that as landing toes first. But I feel like I can say with 100% certainty that no one ever suggested to me that landing toes first could be bad.

I've never felt like I've had weak ankles, nor weak hips (though admittedly I have somewhat tight hips). I've never really hurt—or even had pain in—anything but my knees. Nor have I ever had back pain, supposedly an indicator of hips being used wrongly. So is it possible my knee issues are just...knee issues? If I were to re-evaluate my health issues in light of these books, I'd probably say something like:

My first ACL tear was probably a result of my body being more explosive than my ligaments could handle. With under-strengthened hips/ankles possibly being a contributing factor along with having learned a “toes down” landing style.

My second and third ACLs were a combination of the same factors, plus imbalances stemming from not being fully rehabilitated to a true 100%

My knee issues as an adult (~10+ years after the last ACL surgery) are more just due to my knees being weakened by the combination of injury and surgery. And me not learning earlier that there was still much I could do for them meant that I let those post-surgery imperfections hang around for many years. Another factor in the past few years has possibly been overtraining/ramping up too quickly at points3.

(And of course, bad luck / genetics played a background role in all of this)

Although I wrote above that I worry ACL injuries could just be being traded in for Achilles injuries, for me in particular, it actually seems like a reasonable trade-off. I've never had any Achilles weakness or tendinopathy. Why not trade a little more Achilles stress for a little less knee stress? Sure seems like my knees could use it.

Random bits and pieces

Here are a couple more sections that caught my eye for one reason or another.

This segment discussing baseball should also be of interest to ultimate frisbee players:

Baseball pitchers who can throw the ball ninety-five miles an hour fell into two groups. There were enormous, strong men...[but the] second group tended to be much smaller than average players, and unremarkable in strength tests. But, fascinatingly, they scored exceptionally well on the lateral skater test...And, interestingly, those players had almost all grown up pitching.

Which dovetailed with another baseball mystery: Why was it that every elite player in this sport began playing before the age of twelve?...Many NBA MVPs—Tim Duncan, [Steve Nash, etc]—pivoted to basketball only after puberty. But professional baseball players all grow up playing baseball...

Marcus realized that both mysteries emanate from the same bedrock: baseball is a rotational sport. Rotating is a kind of athleticism barely considered by traditional strength training.

And what's a good sports science book without some crazy story about a study someone did on animals?

Some of the key research into neuroplasticity has been conducted on owls, whose survival hinges on vision. (In some owl heads, eyes comprise a full third of the mass.) Researchers affixed prisms over the eyes of juvenile owls, which meant they would only see clearly by learning to unscramble visual stimuli in real time.

And they did. The owls rapidly sprouted new axons...They built a workaround.

Marcus worked for the New England Patriots at one point before founding P3. I enjoyed this quote:

Marcus remembers Zarins telling him about NFL players coming to camp with known back injuries, and having the strength coach welcome them with maximum-weight squat testing. Marcus remembers Zarins sayin, 'We had two guys blow up in testing." A lot of people assume everything that happens in elite sports is elite. But Marcus says Zarins "knows how dumb it is, because he lives there."

Another sports book I just finished—The MVP Machine—is full of examples of how MLB baseball is the same—an elite level doesn't mean elite thought processes.

As part of his work with the Patriots, he found that "more than half of hamstring strains occurred during the 7-week preseason". Sure seems like correctly ramping up activity levels is an extremely important part of the process of building athleticism—it's also a subject that comes up in The MVP Machine. I may write more on this someday.

Final thoughts

I recommend Built from Broken to anyone who needs to improve their random aches and pains, and hasn't already figured out their "prehab" routine. It's a bit dryer, but is full of useful information.

Ballistic is more of a "good book"—it's well-written; it tells a story with, like, characters; it discusses lots of cool science. Recommended for anyone who might enjoy some "sports science brain candy”. I do feel like I’ve learned a lot about how a body in motion works—but if you're looking for a workout plan, it'll leave you somewhat wanting.

this is perhaps more of a cue than a literal suggestion

Not to mention getting older

Have you looked into having an assessment done by something like P3? A quick google search turned up several places near Boston. One in Foxboro did the whole Movement Assessment Package with force place analysis and 3D movement analysis but they stopped short of making risk assessments.

RE: the tension between P3 and KOTG - in practice is there really much tension at all? He's a big fan of tib raises for ankle/below the knee strength, and of course deep split squats which necessarily involve the hip and ankle