“Of all the machines which civilization has invented for the torture of mankind…there are few which perform their work more pertinaciously, widely, or cruelly than the chair.”

Exercised is by Daniel Lieberman. The subtitle is "Why Something We Never Evolved to Do Is Healthy and Rewarding". The answer, in short, is that humans were shaped by evolution to conserve energy. But we needed to expend energy to obtain the food needed to survive. In other words, it's natural to conserve energy (also known as "being lazy"). But today, food is so easy to obtain that our bodies, which are fine-tuned to expend energy to obtain food, react badly to the low levels of activity that modern Westerners are getting. In fact, we're not any less "lazy" than apes, but apes are evolved for that activity level, while the natural history of humans is a bit more active; as Lieberman notes: "apes and sedentary industrialized people are unusually inactive compared with most mammals, and hunter-gatherers are in-between."

Each chapter starts with a "myth" that will be dispelled: "We Evolved To Exercise", "It is unnatural to be indolent" (see above), "Sitting Is Intrinsically Unhealthy" (hunter-gatherers sit, too, just differently), "Running Is Bad for Your Knees" (elite athletes and new runners do get injured often, but moderate runners are healthier than similar people who don't run), "It's Normal To Be Less Active As We Age" (elder hunter-gatherers are almost as active as younger ones), and more.

Be Moderately Active

The "energy balance" of calories coming in (food) and calories expended by different bodily processes is the focus of the first part of the book. As seen in the figure below, our body can use energy in a few different ways: to grow, to maintain our body, to be stored in our body, or expended through physical activity or reproduction.

One surprising fact from this analysis is that less active women will have higher levels of estrogen, putting them at higher risk for breast cancer:

...the bodies of sedentary women naturally shunt more energy toward reproduction, leading to 25 percent higher levels of estrogen. Because reproductive hormones like estrogen induce cell division in breast tissue, inactivity increases the risk of breast cancer...

So how much activity are modern people getting? It probably goes almost without saying that modern Westerners have very different activity profiles from hunter-gatherers:

...a typical [Western] adult engages in about five and a half hours of light activity, just twenty minutes of moderate activity, and less than one minute of vigorous activity. In contrast, a typical Hadza adult spends nearly four hours doing light activities, two hours doing moderate-intensity activities, and twenty minutes doing vigorous activities.

Average hunter-gatherer men and women (Hadza included) walk about nine and six miles a day, respectively...

Note Lieberman's focus not on vigorous activities but on moderate activities. This is one of the biggest themes of the book: improved health can come through spending more time being moderately active:

...light activities like folding laundry can expend as much as a hundred calories per hour more than sitting. These calories add up. By merely engaging in low-intensity, “non-exercise” physical activities for five hours a day, I could spend as much energy as if I ran for an hour.

Although Lieberman writes favorably about running, lifting weights, and HIIT workouts, to him the "moderate activities" are one of the keys that have been traditionally overlooked, and are important even for people who do engage in vigorous activity. According to one study:

Even those who engaged in more than seven hours per week of moderate or vigorous exercise had a 50 percent higher risk of dying from cardiovascular disease if they otherwise sat a lot.

In addition to hunter-gatherer people walking more than us industrialized folk, he says that another major difference is that hunter-gatherer people are often carrying things when they walk: "All in all, we not only walk less today than we used to but also carry less stuff when we walk. " (Think: children, food, water, etc.)

One thing didn't make sense to me, though: did prehistoric people carry water around the way hunter-gatherers do today? This site suggests that people started using pottery to carry water around 5000 BC, and perhaps before that used wicker baskets sealed with clay or mud, and before that even, used animal skins. (Could people really seal a water skin well enough to keep water in it, 50,000 years ago? That's pretty impressive!) So "carrying things" was part of the ancestral environment, but "carrying big containers of water on one's head" is something done by hunter-gatherer people, but not prehistoric people.

The Inflammation Theory

Aside from the simple fact that time spent being sedentary is not spent being active, he points to two processes through which being inactive harms us:

[One] concern is that long periods of uninterrupted inactivity harmfully elevate levels of sugar and fat in the bloodstream. [Another is that] hours of sitting may trigger our immune systems to attack our bodies through a process known as inflammation.

I'll try to relate his argument about inflammation here, in a version that's as condensed as possible:

[Scientists discovered that] some of the same cytokines that ignite short-lived, intense, and local inflammatory responses following an infection also stimulate lasting, barely detectable levels of inflammation throughout the body...

In the last decade, chronic inflammation has been strongly implicated as a major cause of dozens of noninfectious diseases associated with aging, including heart disease, type 2 diabetes, and Alzheimer’s...

The most widely accepted explanation for how a surfeit of sitting ignites chronic inflammation is that it’s fattening...The body has a finite number of fat cells that expand like balloons. If we store normal amounts of fat, both subcutaneous and organ fat cells stay reasonably sized and harmless. However, when fat cells grow too large, they distend and become dysfunctional like an overinflated garbage bag, attracting white blood cells that trigger inflammation. All bloated fat cells are unhealthy, but swollen organ fat cells are generally more harmful than subcutaneous fat cells because they are more metabolically active and more directly connected to the body’s blood supply. So when organ fat cells swell, they ooze into the bloodstream a great many proteins (cytokines) that incite inflammation.

A second way lengthy periods of sitting may incite widespread, low-grade inflammation is by slowing the rate we take up fats and sugars from the bloodstream...Light, intermittent activities such as taking short breaks from sitting and perhaps even the muscular effort it takes to squat or kneel reduce levels of fat and sugar in your blood more than if you sit inertly and passively for long...although fat and sugar are essential fuels, they trigger inflammation when their concentrations in blood are too high. Put simply, regular movement...helps prevent chronic inflammation by keeping down postprandial levels of fat and sugar.

In addition to moving our bodies, muscles function as glands, synthesizing and releasing dozens of messenger proteins (termed myokines) [that]...help control inflammation. [Researchers] discovered that muscles regulate inflammation during bouts of moderate to intense physical activity similarly to the way the immune system mounts an inflammatory response to an infection or a wound...the body first initiates a proactive inflammatory response to moderate- or high-intensity physical activity to prevent or repair damage caused by the physiological stress of exercise and subsequently activates a second, larger anti-inflammatory response to return us to a non-inflamed state. Because the anti-inflammatory effects of physical activity are almost always larger and longer than the pro-inflammatory effects, and muscles make up about a third of the body, active muscles have potent anti-inflammatory effects. Even modest levels of physical activity dampen levels of chronic inflammation, including in obese people.

In short, (1) swollen organ fat cells put more inflammatory proteins into the bloodstream, (2) Light activity results in less sugar/fat in the bloodstream, which trigger inflammation at higher levels, and (3), muscles that are moderately active release anti-inflammatory compounds. I am not an expert who can judge these claims — they seem reasonable, but given that it's new-ish science and given that the body and metabolism are such complicated topics, I'll remain open to criticisms of this analysis, too.

This seems to both support and refute different aspects of the concept of Health At Any Size. Point (1) seems to suggest that too much organ fat is unhealthy, whether a person is active or not, while points (2) and (3) suggest that different people who are the same size could be more or less healthy depending on if they get their moderate activity.

Sitting

So what's the deal with sitting? First off, another "myth" that Lieberman rebuts is that slouching is bad:

...nearly all high-quality studies on this topic fail to find consistent evidence linking habitual sitting in flexed or slouched postures with back pain...Instead, the best predictor of avoiding back pain is having a strong lower back with muscles that are more resistant to fatigue.

The other important factor is that we don't rest the way that our ancestors did. We can rest, almost completely still for hours at a time, on our couches and beds that are engineered for comfort. In preindustrial environments, it's just not that easy to get comfortable. People may sit on the ground for a while or do some squatting or kneeling, but without the comfortable chairs of modern life, those methods of resting just aren't as comfortable. So people will switch positions, stand up for a minute, or fidget around to relieve pressure points. As discussed above, this base level of activity, even though we wouldn't normally call it "being active", has some unexpected health benefits over being truly sedentary. So while it's natural for humans to be lazy and rest and sit, it's not "natural" (in our evolutionary history) to sit this comfortably.

Other stray thoughts

Above I've recapped some of the most interesting facets of the book; here are some quick thoughts on other topics in Exercised:

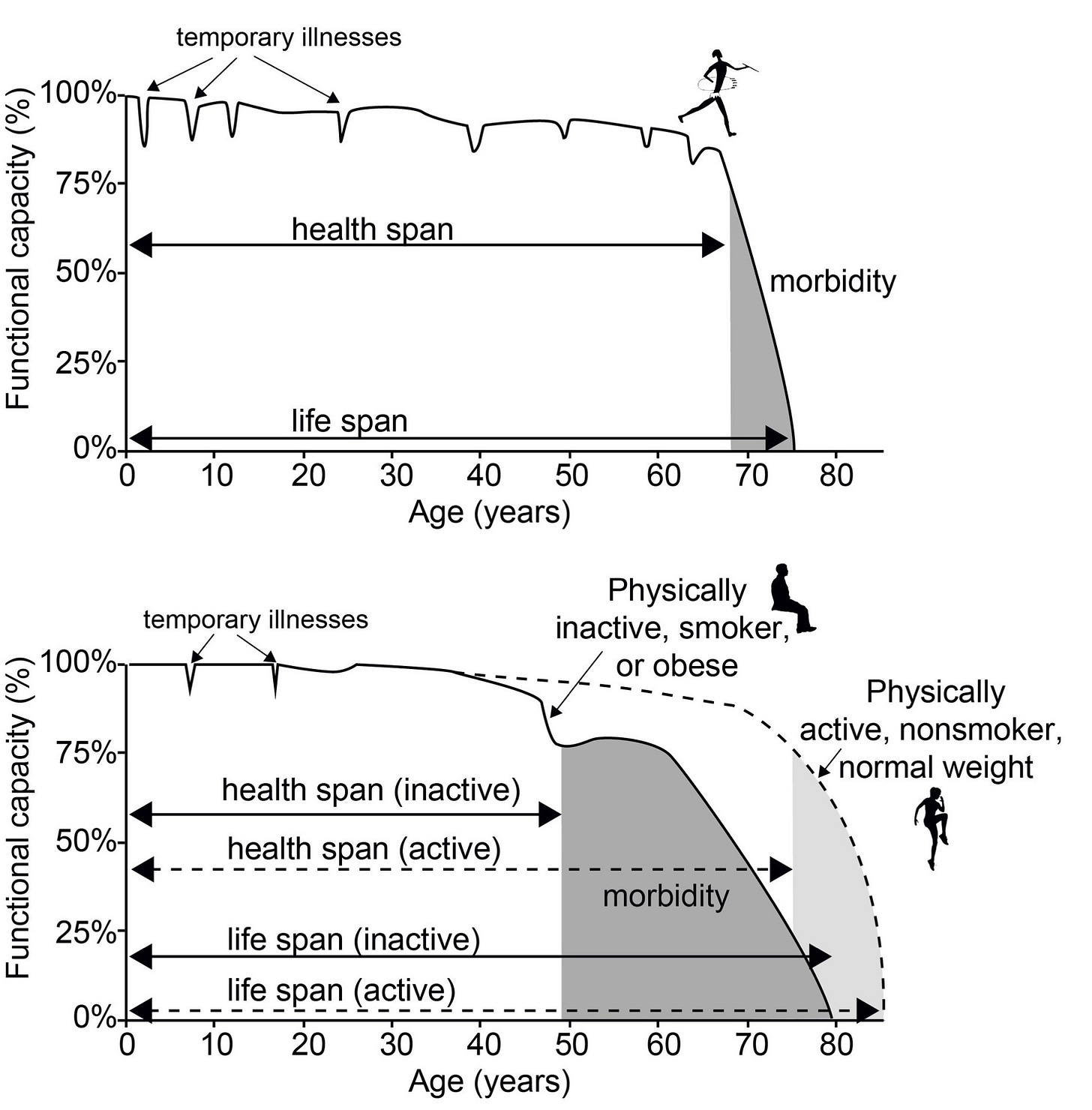

1. As mentioned above, one chapter touches on the question of activity levels in older people. I enjoyed the graphic below. It shows that although the average lifespan of an inactive person is not much shorter than an average active person, the active person will have a higher quality of life for longer. Our modern medical technologies can keep people alive but they won't have the same quality of life as their healthier peers.

2. Losing weight is incredibly hard for a number of reasons. One reason is the energy balance mentioned above — when the body doesn't get enough calories, it cuts back on energy expenditures in all sorts of ways:

...[the bodies of subjects in a starvation study] transformed to use less energy even while resting. After twenty-four weeks of starving, the volunteers’ resting and basal metabolic rates plummeted by 40 percent, far more than expected from the weight they lost. According to the measurements Keys and his colleagues took, the average volunteer’s basal metabolic rate decreased from 1,590 calories a day to 964 calories a day...

Their hearts also got smaller by an estimated 17 percent, and their livers and kidneys shrank similarly.

And another aspect of losing weight that I'd never imagined or read before: on a chemical level, inactive people don't get the same response from activity:

...dopamine receptors in the brain are less active in people who haven’t been exercising than in fit people who are regularly active. And to add insult to injury, people who are obese have fewer active dopamine receptors.

That said, Lieberman argues that it's critically important to get people moving:

From a purely utilitarian perspective, how is requiring exercise different from mandating seat belt use? According to the National Transportation Safety Board, seat belts prevent approximately 10,000 deaths a year in the United States. According to the Centers for Disease Control, inadequate physical activity causes about 300,000 deaths a year in the United States—thirty times more.

3. I thought this story was interesting: some studies have suggested that running can put people at risk of heart issues, but this relied on an incorrect understanding of plaques in the circulatory system:

These calcified plaques can cause a heart attack if they block an artery. Because plaques contain calcium, which shows up nicely in a CT scan, doctors routinely score plaques by their calcium content: a coronary artery calcium (CAC) score. CACs above 100 are generally considered cause for concern...

...[researchers] find that the dense coronary calcifications commonly found in athletes tend to differ from the softer, less stable plaques that are indeed a risk factor for heart attacks. Instead, they appear to be protective adaptations—kind of like Band-Aids—to repair the walls of arteries from high stresses caused by hard exercise. One massive analysis of almost twenty-two thousand middle-aged and elderly men found that the most physically active individuals had the highest CAC scores but the lowest risk of heart disease.

4. Lieberman is one of the originators of the "Born to Run" theory — though as he stresses in this book, we are also "born to" be no more active than necessary. But he does continue to maintain that humans are pretty good at running, especially for long distances:

If I may brag: I beat forty of the fifty-three horses [in a combined human/horse marathon event] despite an unremarkable time of 4:20...

...[Contrary to popular misconceptions] humans run as efficiently per pound as horses, antelopes, and other species well adapted for running.

Does life need to be hard?

It's really annoying, in a way, that humanity just can't "win". We invent foods that taste really good, but we can't eat them as much as we'd like without becoming unhealthy. We invent incredibly comfortable objects to sit on, but we shouldn't sit on them too long or else we'll become less healthy as well. To paraphrase (and take out of context) the Buddha, life is suffering. After millions of years of evolution, all of which required our ancestors to "suffer" to survive (or at least to walk a few miles to obtain food), in a nasty twist of fate our bodies are now adapted to an environment that includes suffering. In a modern environment that doesn't force us to suffer, our bodies won't work right without a "healthy" amount of suffering (or at least walking a few miles before dinner).

Although Lieberman doesn't really ever come at it from this angle, the mismatch between our evolutionary environment in terms of activity levels is compounded by the mismatch with our diets.

Luckily, it's not all that bad — many of us truly enjoy playing sports or taking a walk after dinner. We don't have to purely suffer to stay healthy, we can have some fun doing it. And as noted above, late-in-life morbidity (that comes after too many years of inactivity) is directly painful, so it's not just a matter of suffering more, but instead that we need to suffer a little more now to suffer a little less later. Similarly, eating healthy food can still be pretty tasty, too.

Exercised is interesting and informative. I will try to change my lifestyle based on the book's suggestions: doing a bit more walking, and taking few more breaks to keep my muscles a-little-bit-active when sitting for long periods of time.