Welcome to another round of mini book reviews (here was the first one). Nonfiction at the top, a few fiction titles down at the bottom. I recently finished my 500th(!) book since I created the spreadsheet I currently use to keep track of my reading (fittingly enough, almost exactly 10 years ago to the day).

My reading has slowed down recently. I can think of a couple reasons for that: one, I'm growing more interested in doing things and creating things instead of reading about things. And two, it's harder to find something that feels truly new after having read so much (though, to be sure, there are people who've read lots more than I have). Anyway, here we go:

Nonfiction:

The Disordered Cosmos by Chanda Prescod-Weinstein

I didn't really connect with The Disordered Cosmos (which is not the same as saying that I thought it was wrong about anything). I didn't take many notes on this one so at this point I've forgotten most of what I read and I can't back up that feeling with any specific examples.

The book is partly about physics and partly about the author's experiences as a "queer agender Black woman" in particle physics. There are sadly, you probably won't be surprised to hear, still very few Black women in physics. Perhaps the reason I didn't connect well with the book is that in recent years I've read lots of similar (nonfictional) stories, whether in books or online. It's still a powerful story, but I've read enough of them that what I need to do at this point is help change things, not just read more stories.

Arbitrary Lines by M. Nolan Gray

A good book about zoning and zoning reform. I've started working on a longer review that I still hope to post at some point. This quote about the legal history of zoning was a bit shocking. (though in the past few years we've come back around to being comfortable with the idea the Supreme Court is biased):

In 1926, the Supreme Court gave zoning its blessing in Euclid v. Ambler...In a six–three majority decision, Justice George Sutherland characterized apartments in low-density neighborhoods as “mere parasites.”

Besides being classist, it'll surprise no one that zoning was invented for racist reasons as well:

While laundries historically could pose fire risks, the risk offered by Charles Henry Cheney, a key framer of Berkeley’s 1916 zoning ordinance, is that they bring in “negroes and Orientals.” Indeed, the Berkeley city attorney separately characterized Berkeley’s zoning proposal as part of a broader California tradition of segregating away “heathen Chinese.”

I'm really interested in zoning reform (keep reading for some other books about land use). It has the potential to appeal to people on the right politically (get rid of regulations so we can be freer!) as well as the left (help poor people!).

Why Fish Don't Exist by Lulu Miller

Why Fish Don't Exist is perhaps my favorite book in this post. The book had a lot of narrative twists and turns: first it was a history book about a great scientist, then it became a book about the author's personal story. We dove into the science of classifying organisms:

Like, for example, as much as a bat might look like a winged rodent, it’s actually more closely related to camels. Or that whales are actually ungulates (the family to which deer belong)!

And then all of a sudden it was a murder mystery. Finally it somehow all came together to discuss inequity in our modern world.

Cesar's Rules by Cesar Millan and Melissa Jo Peltier

I read this book while dogsitting a dog that didn't like me, and by the end of the week we were good friends. OK, it wasn't all because of the book, but I did learn a few useful things. I've seen that Cesar gets some hate online for an "I'm the alpha dog"-type training philosophy and/or using negative reinforcement. I haven't followed the debate all that closely, so take this with a grain of salt, but I liked the way Cesar brought up these issues in the book.

First, he didn't shy away from pointing out that these differences exist. Second, he was overall still very pro-dog — believing that dogs should be able to feel happy, safe, and fulfilled. The way he phrased things was less "you need to be the alpha!" and more "your dog will look to you as the leader of the family; you can help it feel happy and comfortable by providing that leadership". And I thought his explanation for how his philosophy developed was quite reasonable: he grew up watching packs of dogs and learned how they behaved, and so interacted with them in ways he saw they were capable of understanding (for example, dogs might give another dog a quick bump to correct their behavior, so he learned to do the same).

There were a couple training tips that have stuck with me after reading the book:

Don't look dogs in the eye when they are new to you. Dogs don't use eye contact the same way we humans do, and it's better to semi-ignore a new dog as you get to know it.

"Capturing" behaviors: for example, instead of teaching a dog to sit by forcing it to sit on your command and then giving it a treat, you can watch the dog until it decides for itself to sit and then quickly say "sit" and give it a treat.

I wasn't really able to connect with his insistence (it came up a number of times) that things other than food treats can be used for motivation—like letting the dog sniff or play with a favorite toy. I still haven't been able to figure out how to do this in my own dog-relationships, but hopefully I'll get there someday.

Several Short Sentences About Writing by Verlyn Klinkenborg

This book fits in near the top of my mental list of the best books about writing. But perhaps that's just a reflection of the writing style I'm attracted to. It really is a book about (and written in) short sentences:

They’ll sound strange for a while until you can hear what they’re capable of.

But they carry you back to a prose you can control,

To a stage in your education when your diction—your vocabulary—was under control too...

You’ll make long sentences again, but they’ll be short sentences at heart.

I liked the following bit, about the challenges of recognizing what your own writing says and how other people might interpret it.

This brings us back to the difficulty of knowing what your sentences actually say.

The problem most writers face isn’t writing.

It’s consciousness.

Attention.

Noticing.

That includes noticing language.

It's probably not a surprise to you that I highlighted this section. I'm a big believer in the importance of noticing things.

There's a tender balance between being overly wordy and making your sentences so short that a reader can't figure out what you were thinking. He argues against using phrases that handhold your reader through the argument:

On the one hand.

On the other hand.

Therefore.

Moreover...

These are logical indicators. Emphasizers. Intensifiers.

They insist upon logic whether it exists or not.

They often come first in the sentence,

Trying to steer the reader’s understanding from the front,

As if the reader were incapable of following a logical shift in the middle of the sentence...

These words take the reader’s head between their hands and force her to look where they want her to.

Imagine how obnoxious that is...

But at the same time, he's aware of how hard successful communication can be:

It’s surprising how often ideas that seem obvious to you

Are in no way apparent to the reader.

I tend to use some of these phrases because communication is hard, and I know people are going to have more trouble understanding me than I have understanding myself. Since many of my posts are written to share useful information, I want that information to be successfully transferred. I'd prefer a few extra people saying "that's obvious" to a few extra people saying "huh?". But we all have to find the right balance between confusing our reader and insulting their intelligence.

Why Can't You Afford a Home? by Josh Ryan-Collins

I've started writing a longer review of this book which I still hope to post someday. I didn't love the book but he had some interesting points.

Here's the way-too-short answer to the title's question: We have a limited supply of land—we can't make more land when lots of people want it (compared to, for example, how Apple can make more iPhones when lots of people want to buy iPhones). But we DO have a near-infinite supply of mortgages (not to mention a rising population...and a class of voters who don't want the value of their homes to go down).

Add those factors together and we get more and more money trying to buy the same homes. On top of that, banks prefer making mortgages to lending money to business because mortgages are always backed up by a real asset—the bank can claim the property if the mortgage isn't repaid. The same might not be true when a bank makes a loan to a small business.

What's the solution? Well one option is more regulation around mortgages. The other option is to learn that Land is a Big Deal—and tax it. He wrote a whole book about the complexities of our mortgage and finance systems, just to point out in the last chapter that one tax law could fix it all:

Economists, famously, agree on very little. But one exception is that a regular tax on the increasing value of land – a land value tax (LVT) – would be a very good idea... Whilst there are a couple of different variants, the basic conception of an LVT would be an annual tax on the incremental increase on the unimproved market value of land that would fall upon the owner of that land.

Land is a Big Deal by Lars Doucet

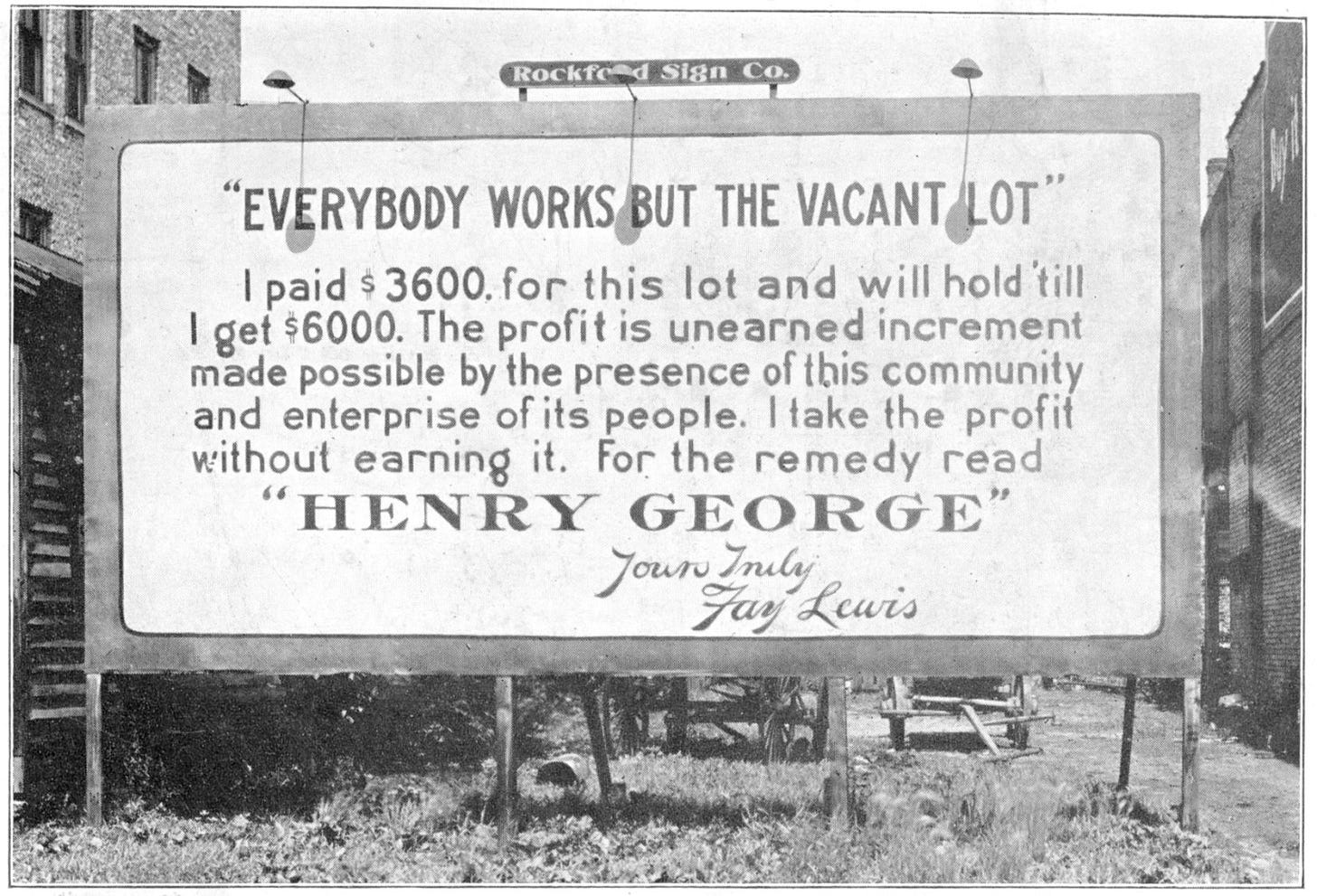

I've been quite interested in Georgism and land use for a couple years now. I haven't gotten into the details on any of these books because I feel like I can't do these ideas justice in the amount of words I'm trying to keep this to. If I ever get around to it, I'll write my own introductory explanation of Georgism some day. As a super-quick introduction, check out this graphic that was posted on Reddit recently.

But if you're the type of person who reads books about politics and the economy, give this one a try. If you've ever wondered why we've invented so many new things but instead of utopia there's still so many poor people, this book has an explanation:

Every labor-saving invention, whether it be a steam plow, a telegraph, an improved process of smelting ores, a perfecting printing press, or a sewing machine, has a tendency to increase rent.

I don't think it's the best-possible introduction to Georgism, but until someone writes that book, this one is a pretty readable option.

Rethinking the Economics of Land and Housing by Josh Ryan-Collins et. al.

Perhaps my least favorite of the land-use books here. There's too much talk of data points and regulatory changes, etc. The biggest new thing I took from this book was a few of the quotes from a few famous economists/philosophers back in the day. Adam Smith is famous as "the father of capitalism", which might give him something of a bad name among people today who are frustrated with capitalism. But he was not ignorant of these issues, in fact he pointed them out:

As Adam Smith noted in The Wealth of Nations (1776, p. 162):

The rent of land, therefore, considered as the price paid for the use of the land, is naturally a monopoly price. It is not at all proportioned to what the landlord may have laid out upon the improvement of the land, or to what he can afford to take; but to what the farmer can afford to give.

And:

[Smith] held property to be an acquired right that was dependent on the state and its form. Smith believed that civil government could not exist without property and that its main function was to safeguard property rights. Like Locke, however, he had concerns about the inequalities that could arise from the relationship between the state and property, arguing that: ‘civil government, so far as it is instituted for the security of property, is, in reality, instituted for the defense of the rich against the poor, or of those who have property against those who have none at all’ (Smith, 1776, p. 167).

John Locke is known for arguing in favor of private property rights, which again would seem to make him a bad guy in a book about "rethinking economics". But it turns out the problem isn't the ideas Locke came up with, but how far away from them we have drifted since then:

Often overlooked in Locke’s work, however, was the ‘Lockean proviso’ that property was only natural so long as there was sufficient common land for others to enjoy. Locke believed that there was plenty of unclaimed land in America, so that the rules for a time when land was not scarce applied to the time when he was writing, and he did not need to deal with the eventual scarcity of unclaimed land. Since in most advanced economies all land is owned, it is not clear the Lockean justification for private property in land still has legitimacy.

Land: A New Paradigm for a Thriving World by Martin Adams

Hopefully you're convinced by now that I'm quite interested in land use! I've considered starting a second blog to focus on land use issues. We'll see if I can actually find the time to do that. Here's a random interesting quote from Land (you can read the book for free on the internet):

The payroll tax, for example, punishes businesses and entrepreneurs for creating jobs for the economy, while consumption taxes such as sales taxes discourage access to perhaps much-needed goods; capital gains taxes deter investments, while property taxes on buildings discourage the creation of affordable housing and inhibit the beautification of neighborhoods. In short, our current tax system is in most respects a lose-lose proposition.

These four books all have things that I think they do well and other things I think they don't do quite as well in terms of being "the book" people should read to understand the subject. Land does the best job at introducing the moral aspects of land use issues:

almost everything in our daily lives connects us to actions performed by other people—past actions that leave anonymous footprints on our lives today.

Of Boys and Men by Richard Reeves

A book about the struggles boys and men face in today's society (which is, obviously, not to say that girls and women don't face struggles as well):

So we have an education system favoring girls and a labor market favoring men...One gap is narrowing, the other is widening.

One of his biggest ideas is that we need to have boys start school later (so, for example, first grade would have six-year-old girls and seven-year-old boys). He points out that boys and their brains develop more slowly:

The cerebellum, for example, reaches full size at the age of 11 for girls, but not until age 15 for boys.

And shares some studies showing that many kids, boys especially, benefit from starting school later:

A raft of studies of redshirted boys have shown dramatic reductions in hyperactivity and inattention through the elementary school years, higher levels of life satisfaction, lower chances of being held back a grade later, and higher test scores.

Given that some boys are going to repeat a grade anyway, he argues we'd do better setting them up for success by starting them a year later instead of setting them up for failure by sending them to school too young until they one day need to repeat a grade:

one in four Black boys (26%) have repeated at least one grade before they leave high school. By redshirting boys from the outset, we can reduce their risk of being held back a year later on.

He shoots down a few counterarguments to boys starting school later, but he didn't discuss the one aspect that I immediately thought would make it the hardest to implement this policy: there's already such a cultural meme of needing to protect our teenage girls, would people really be willing to send them to school with boys who are older than them?

So what other issues are boys and men facing? Girls and women straight up do better in school by a number of statistics—only about 41% of college students are men. On top of that, many studies seem to show that our efforts to help people (in education and otherwise) work better on women than men:

Thanks to an anonymous benefactor, students educated in [Kalamazoo, MI]'s K–12 school system get all their tuition paid at almost any college in the state.

But the average [benefit of the program] disguises a stark gender divide. The program put rocket boosters on female college completion rates, increasing the number of women getting a bachelor’s degree by 45%. But men’s rates didn’t budge. A cost–benefit analysis shows an overall gain of $69,000 per female participant—a return on investment of at least 12%—compared to an overall loss of $21,000 for each man (in other words, it was expensive and didn’t work).

He then goes on to discuss a number of other studies like this.

In the work world, while men out-earn women, only the men who are at the top of the income distribution have seen their wages grow over the last few decades:

The median real hourly wage for men peaked sometime in the 1970s and has been falling since. While women’s wages have risen across the board over the last four decades, wages for men on most rungs of the earnings ladder have stagnated.

He hypothesizes that a main reason men have lost their way is that they have a less "obvious" role in society. A woman's role as a mother is "inscribed in [her] body"—because they get pregnant and give birth, they have a clearer connection to motherhood. Men's traditional role as protector and breadwinner has dissipated as society has changed enabling women to earn their own living (which is obviously a good thing overall). That has left them with a somewhat unclear role in society. Going back to the past isn't the answer, and I'm sure we'll develop a "new role" for men in society, but at present we're in this weird in-between period where a lot of men are lost and disconnected.

I was a bit disappointed in the book, overall. I had heard of a few of these issues before, including reading the transcript of a podcast the author was on (this one maybe?). I didn't feel like I learned all that much beyond what I already had read. If you've read this review and read through that podcast you probably don't need to read the whole book.

2030 by Mauro F. Guillén

The subtitle is How Today's Biggest Trends Will Collide and Reshape the Future of Everything. Perhaps it's because I read a lot of tech news, or perhaps it's because we've already reached the 1/3 mark between when this book was published and 2030, but I wasn't super impressed. It seemed like a mixture of things I already knew about (the population will continue changing—getting older in developed economies, getting larger in southeast Asia and Africa) and things that don't seem like great predictions at this point (based on what we know right now, I felt like he overestimated blockchain and underestimated AI).

The one thing that I'd never thought about before ties in nicely with the previous review: by 2030, there will be more global wealth owned by women than by men. That seems incredible given how high-level roles like CEOs & etc. are still male-dominated. Part of this transfer is because women, on average, live a few years longer. Some of those old ex-CEOs will pass away and their widows will control the family fortune. (Though, to be sure, the bigger reason for this shift is that women worldwide are becoming freer and more successful.)

Fiction:

Piranesi by Susanna Clarke

I'm a huge fan of Clarke's Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell. Piranesi is much shorter, but still has that beautiful magical feel.

The Rise and Fall of D.O.D.O. by Neal Stephenson and Nicole Galland

I read this book when it first came out in 2017 or so. I caught a cold a few months back and for some reason decided re-reading The Rise and Fall of D.O.D.O. was how I wanted to pass my time. I very rarely re-read books so I'm not exactly sure how I decided on this one. Neal Stephenson is one of my favorite authors but I hadn't thought of DODO as one of my favorite books by him. But I enjoyed my re-read, perhaps more than I enjoyed it the first time.

DODO is a long, fun book with time travel, witches, Vikings, and lots more. (A review quoted on Wikipedia says the "story gets weirder and more madcap" as it goes, but [is] "a pleasing combination of much appeal to fans of speculative fiction.")

The Dead Romantics by Ashley Poston

I feel like every love story needs some excuse for the characters to be in contact but not be together for most of the book. The Dead Romantics comes up with an interesting conceit. Not my typical reading material but it was a nice change of pace.

Babel by R.F. Kuang

I really liked the world of this book (very reminiscent of Jonathan Strange, mentioned above) and I really liked the first 2/3rds of it. I wasn't a huge fan of where the plot went towards the end. I've also read Kuang's The Poppy War and the two books both had a similar issue (to my personal taste): in the second half of book, the plot and characters became darker and more violent than I was expecting. Some sources call this book Babel, or the Necessity of Violence, (although that title wasn't in the copy I read), so I'm not sure what I was expecting.

But personally, for whatever reason, I found the last third of the book unsatisfying. I think there could have been a somehow different plot that imparted the same worldview. But plot can be very much a question of personal taste. If you love books about language or you love beautiful magical worlds that are just a little different from ours, give this book a try. (After writing this, I happened to discuss the book with a friend who had the very same complaints. But we're both privileged white people who may be coming at it from our own privileged biases—which may be relevant given the themes of the book.)