LeBron James's "high IQ moments" highlight video has millions of views. Yes, his body is a finely tuned machine—but his brain is, too. In-game smarts can be a difference-maker on the frisbee field, too. But I've never found good articles that explain, in clear terms, the mental processes going on in these situations. I've written this essay to start to explain how to play "high IQ" ultimate.

Playing sports well is hard and takes many years of practice. The skills I discuss here have to be developed over time until they become innate. Reading this essay won't immediately make you better at ultimate. But this essay will explain part of what being a "smart" player entails. My goal is that knowing what to shoot for will help you become a smart player much faster than you would just by playing lots of frisbee and hoping.

OODAs

This profile on Cooper Kupp was the first time that I heard the term OODA:

Cooper Kupp loves talking ball and never hesitates to share the nuances of his craft. Back in July, Kupp explained his approach to football, asking reporters whether they were familiar with “OODA loop,” an acronym for a strategic military concept that incorporates a four-step decision-making process.

“That’s football,” Kupp said while motioning his finger in a circle. “Observe, orient, decide and act, over, and over, and over again. The quicker you can do these things, the better you’re going to be. The slower the game is going to be [mentally], the better you’re going to be.”

Perhaps Kupp’s greatest attribute is his ability to diagnose situations in real time.

In other words, you notice things, and then you figure out what you can do to help your team based on those things that you've noticed. Observing is, in a way, the easy part—mostly you just need to look around (listening can also be important, at times). We'll talk about that first.

Noticing

Meditating on the Field

My first exposure to the idea of noticing things came a few years before learning the term OODA. I've long been interested in meditation (although I'm still not any good at it). Reading meditation books I'd learned that one of the most well-known meditation techniques is noting. The idea is that...you notice things. Lots and lots of things. Whether it's a thought you're having, a noise you're hearing, or the feel of some air blowing past your skin, you aim to continuously notice the sensations and experiences that are making up your present moment.

Here's a discussion of noting from the book Mastering the Core Teachings of the Buddha:

Our minds have the power to perceive things extremely quickly, and we actually use this power all the time to do such things as read this book. You can probably read many words per second. If you can do this, you can certainly do insight practices.

If you can perceive one sensation per second, try for two. If you can perceive two unique sensations per second, try to perceive four. Keep increasing your perceptual threshold in this way until the illusion of continuity that binds you on the wheel of suffering shatters. In short, when doing insight practices, constantly work to perceive sensations arise and pass as quickly and accurately as you possibly can [sic?]. With the spirit of a racecar driver who is constantly aware of how fast the car can go and still stay on the track, you are strongly advised to stay on the cutting edge of your ability to see the impermanence of sensations quickly and accurately...

The technical meditator may easily sit for hours dissecting their reality into extremely fine and fast sensations and vibrations, perhaps even up to 40 per second or even more, with an extremely high level of precision and consistency.

Frisbee isn't meditation, and no one is noticing 40 things per second while playing ultimate. We can find our own appropriate level. You don't need to keep increasing your perceptual threshold until the illusion of continuity that binds you on the wheel of suffering shatters. But if you get a little closer to there than you are now, it'll almost certainly help your ultimate game grow.

In my experience, a good unit of time for noting in ultimate is not one second but one player's possession of the disc. If you can notice an extra two things between the time one player catches the disc and when they throw it, you'll have significantly stepped up your game.

What things should you notice?

Now you know to notice things. The next step is to figure out what things to notice. Let me give a quick example. As a cutter, here are some things I'm constantly checking in on:

Where is my defender positioned relative to me?

What is my defender seeing? (I've written about this)

Are any other defenders watching me?

Where is the person holding the disc looking?

What's the stall count?

What is the positioning of the person marking the thrower?

Where are the open spaces on the field?

Are any other cutters already open? Has the thrower noticed them?

This is a basic list that I wrote in a couple minutes—it's enough to get you started. Many of my other articles build off this idea, and I'm sure you can come up with lots of ideas yourself for things that you could benefit from noticing in a given situation on the field.

Some examples of noticing

Here are two video clips that exemplify what it looks like when athletes notice things.

First, from the NBA. Watch the clip below (trimmed from this Thinking Basketball video) of Draymond Green playing defense. He's the one who's circled a few seconds into the video—wearing #23.

What I want you to watch is the way he uses his head and his eyes. The ball is on one side of the floor, while the person he's assigned to is on the other side. He looks back and forth between them repeatedly, checking in on both so he can respond to both. By my count his eyes make maybe 6 round trips (from the ball, back to his person, back to the ball) in 12 seconds of game time.

In ultimate, I was very impressed watching Levke Walczak play defense in the 2022 national semifinal between Brute Squad and Fury. Watch the clip below, and again, pay attention to how much she turns her head. We see the same thing we saw Draymond doing — going back and forth between the disc and the person she's guarding (not to mention looking for opportunities to play help defense on other cutters).

For anyone who might not know, she's #42—you'll see her playing defense downfield after the first pass is caught ~5 seconds into the video:

By my count, her eyes make about 7 round trips (disc, to her person, back to disc) in 14 seconds — about the same rate as Draymond in the previous video. Watch below:

As I've written before, physical skills are needed to make use of your mental skills. You need to be comfortable with different ways of moving (shuffling, backpedaling, etc) and with looking in different directions while moving. Being comfortable with moving backwards, moving sideways, and having the clean footwork to switch between many different modes of movement is a must to get the most out of your mental skills. This is what it looks like to keep your head on a swivel.

Not everyone can be LeBron James, of course. But on a whole, frisbee players could be a lot better at playing like Levke and constantly scanning the field instead of being hyper-focused on one thing at a time. For example, take a look at this video Hive Ultimate recently posted to Reddit where a player runs the full length of the field and gets wide open in the endzone because no one played help defense.

If there's one thing I hope most people take from this article, it's this. Play like Levke—look around the field more! Everything else grows from doing that.

Analyzing

What are you tracking?

"What Are You Tracking In Your Head?" is another essay that came across my radar recently. The article discusses the importance of the things we're keeping track of in our heads while performing some skill:

The common pattern among all these [examples] is that, while performing a task, the expert tracks some extra information/estimate in their head. Usually the extra information is an estimate of some not-directly-observed aspect of the system of interest. From outside, watching the expert work, that extra tracking is largely invisible; the expert may not even be aware of it themselves. Rarely are these mental tracking skills explicitly taught...

For purposes of learning/teaching, the key question to ask of a mentor is “what are you tracking in your head?”; the key question for a mentor to ask of themselves is “what am I tracking in my head?”. These extra-information-tracking skills are illegible mainly because people don’t usually know to pay attention to them. They’re not externally-visible. But they’re not actually that hard to figure out, once you look for them. People do have quite a bit of introspective access into what extra information they’re tracking. We just have to ask.

Though the essay isn't about sports, it has a lot in common with what I've written here. One commonality is the way these skills are implicit ("the expert may not even be aware of it themselves") and that leads to them not being "explicitly taught" enough. Another is that we're tracking things that are "not-directly-observed" (for more on that, keep reading). Then there's the idea that we can teach these skills, if we try ("people don’t usually know to pay attention to them... But they’re not actually that hard to figure out, once you look for them.").

This essay helps clarify the least obvious part of the OODA Loop (Observe, Orient, Decide, and Act). To me, it's obvious what Observe is: you look around and notice things. It's also pretty obvious what Decide and Act are: you figure out what to do to help your team win, and you do it.

Orient is the one term whose meaning is not immediately clear. And that's where tracking things in your head fits in: You're not just noticing things and making decisions, you're taking those things you've noticed, and mentally adding them on top of all the other things you know and have been paying attention to and tracking. Just like we work on our skill at noticing things, we need to develop our ability to keep track of things that we're not currently looking at.

Keep track of things

So noticing things isn't very useful if you can't keep track of them. We have to be able to remember what we saw and make a guess at how they're changing while we're not looking at them. Think about what Levke Walczak was mentally doing in the video above.

At the moments she's looking at the thrower, she can see from their body positioning and their eyes which parts of the field they're paying attention to. Once she's gotten that information, she shifts her focus back to both her assigned person (and to checking in on other matchups around the field to see if there are any help opportunities).

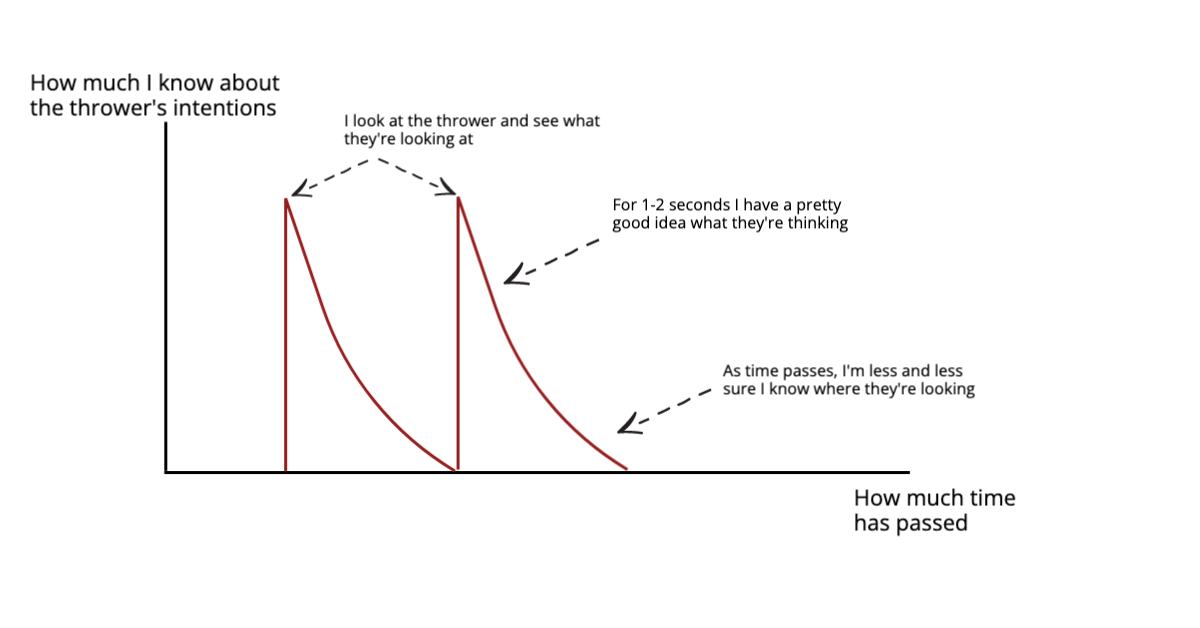

In the back of her mind, she's remembered where she saw the thrower focusing their attention. She knows that for the next 1-2 seconds, she can be confident they are looking there, but as time passes she's less and less sure of what the thrower is looking at anymore. She can't assume anymore that only that part of the field is of critical importance. She's mentally keeping track of where the thrower was looking, and the time that's passed since she made that observation. After a couple seconds, she looks at the thrower again to regain that knowledge. I made a diagram for you visual learners:

On the offensive side of the disc, consider the example of holding the disc looking for someone to throw to. I look downfield for a couple beats, and then look towards the dump handler. When I'm looking at the dump option, I can't see downfield. But, I still remember what I saw the last time I was looking downfield, so if the immediate option doesn't get open, I already have an idea what to expect as I turn my eyes back downfield.

In fact, I'll sometimes use this as a purposeful technique—when I have the disc & I see someone start to get open, I'll actually look away from them. If a downfield under cut starts to come open, I might look momentarily towards the dump. This will usually shift my mark towards the dump space. But in my mind I'm keeping track of the under cut. When the moment arrives that I think I want to throw it, in one quick motion, I'll look back downfield, confirm that they're as open as I expected, and release my throw before my mark has a chance to get back into a position that could disrupt my downfield throw.

An easy throw was made possible by noticing things and then keeping track of them in my mind while looking at something else.

Noticing things, remembering what you've noticed, and making an educated guess as to how it will develop over the next 1-2 seconds. This skill is at the core of playing sports at a high level.

Perspective-taking and simulating

In the examples above, "keeping track" doesn't just mean "remembering"—it also involved some amount of understanding/estimating/predicting how things would change while you weren't looking at them. Another way to look at it: like Dr. Strange finding a path for the Avengers to defeat Thanos, the mental process is all about simulating:

We're constantly simulating the future, a couple seconds at a time. We notice one part of the field, then, while we look at a different part of the field to try to notice more, we're simulating what's going on in the places we're not currently looking.

When we're trying to predict what other people will do, we need to know what they know. A big part of my noticing process is not just noticing where people are but noticing what they're looking at. Knowing what someone is paying attention to allows me to predict their immediate future more accurately.

Perspective-taking is usually thought of as something we do when we're thinking about communication and empathy. Sports has its own variant of perspective-taking—thinking about what other people are thinking is a skill we can use to play sports better.

As I've said before, simulating other people's brains while playing is more of an instinctual skill than an explicit skill. If we have to consciously think about doing it, we'll do it too slowly for it to matter. But if we build up our skill at perspective-taking/simulating over time, we can make it an instinct. Just like with physical skills, like throwing a flick, we'll go through a period where we do it badly and we have to think about it each time. But with enough practice it'll become instinctual.

Other considerations

Build up your mental endurance

A previous article of mine included this GIF of Mad-Eye Moody teaching his students about constant vigilance:

We have to treat building up our mental (noticing and simulating) endurance the same way we treat building up our physical endurance. Over time, we improve our ability/stamina at noticing things without getting too drawn in to any one thing. This is especially true on defense, since it's reactive by definition—we can't fully take the initiative, we have to see what the offense does and respond to it.

Making highlight-reel layouts isn't the only way to be great at defense. There's a whole other skill that doesn't make it onto highlight reels—noticing things and repositioning, noticing and repositioning, over and over again. When it's done perfectly, all it looks like is the offense not having good options. (For the same reason, in pro football, the best defenders don't get the most interceptions—the person they're guarding isn't open so the ball doesn't get thrown near them in the first place.)

Great defenders are highly skilled at constantly noticing things without getting distracted. One momentary distraction is all a skilled offensive player needs to get open for a score. It takes years to slowly build up that ability to be always on, always noticing things, constantly vigilant.

The same is true on offense, though perhaps to a lesser extent. Our goal should be to be always on, always noticing things, always looking around and taking in the field. Too many people still turn their brains off for a moment after throwing a pass. Too many people think standing in the middle of the stack is a good time to let other people do the thinking for a while. Frisbee should be an intellectual challenge.

We want to notice things while not getting drawn in so much we completely forget about the things we're not currently looking at. This is another way playing sports is like meditation—both involve building up the mental skill of focusing and avoiding distraction. In meditation, we typically want to focus on something like our breath while avoiding the distraction of any thought that might arise. In sports, we need to stay focused on keeping the big picture in our mind without getting distracted by the thing we're currently looking at.

Don't forget the other skills

Noticing things is the idea that I expect most people will take away from this article. But noticing things is just one part of the OODA loop. Being better at noticing things won't, by itself, make you a high-IQ frisbee player.

You also need to have ideas already in your brain of what you might do next. That's what many of the other articles I've written are about — all the different little tricks that you should have in your bag of tricks. That's the "Orient" section of the OODA loop—combining the things you notice in the present moment and the knowledge that's already in your brain to come up with the optimal Decision. Or as the originator of the OODA loop says, "The second O, orientation—as the repository of our genetic heritage, cultural tradition, and previous experiences—is the most important part of the O-O-D-A loop since it shapes the way we observe, the way we decide, the way we act."

In other words, we can't just get better at doing OODA loops, we have to also fill our brain up with the frisbee knowledge that allow those loops to come up with the best Decisions. Some of that knowledge already in your brain is explicit—tricks you've learned from reading this blog or watching Rowan's YouTube videos. Other knowledge is implicit—instincts developed from actually playing lots of frisbee.

The point is, learning to notice things is just one skill among many on the path to being a great frisbee player. You won't become a great player without it, but it alone won't make you a great player, either. It has to be combined with your previous experience and the tricks you've learned before you can both see opportunities and take advantage of them.

In summary

Look around the field and notice things. Even elite players don't do this enough, yet. Done right, it's a meditative/flow state experience. Use those things you've noticed and: keep track in your head / simulate the future / figure out what others are thinking. It needs to be an innate skill, but thinking about it explicitly will help it become innate more quickly.