Read my book reviews instead of reading whole books! Learn a little bit about something you otherwise never would've read about. Or maybe find your next book if you like reading.

See here or here for similar articles I've posted previously.

Feel free to skim. Non-fiction first, with a small fiction section at the bottom.

Nonfiction:

Code by Charles Petzold

A lot of people say this is THE book about how computers and code work, that it's both beautifully written and technically accurate. (For example, the first Amazon review says "I think that this is the best book that I have read all year. In some sense this is the book that I have been looking for for twenty-five years—the book that will enable me to understand how a computer does what it does.")

I really enjoyed the first half or so of the book, but around chapter 14 or 15, he started to introduce new concepts a little too quickly, and my eyes started to glaze over a little. In the end, I certainly do understand computers better than I ever did. But the first half or so about the book, about electricity, binary code, and basic electronics, were what really met the expectations from those reviews I'd read.

On electronics:

The relay is a remarkable device. It's a switch, surely, but a switch that's turned on and off not by human hands but by a current. You could do amazing things with such devices.

And electricity:

Electricity is like nothing else in this universe, and we must confront it on its own terms...

We normally like to think of a battery as providing electricity to a circuit. But we've seen that we can also think of a circuit as providing a way for a battery's chemical reactions to take place...

The earth is to electrons as an ocean is to drops of water. The earth is a virtually limitless source of electrons and also a giant sink for electrons.

I was struck when he pointed out how easy multiplication and addition are for binary numbers. In our base-10 system, we have to memorize 2*3 and 6*8 and 9*5 and all those different combinations to be adept at multiplication. In binary, the entire multiplication table consists of: 0*0=0, 0*1=0, and 1*1=1. That's it. You just need to know those three rules to multiply huge numbers together.

Wild Problems by Russ Roberts

I didn't really get into this book but I could see it working for other people who'd like to read a short book that gets them to think about what they find important in life. The subtitle is A Guide to the Decisions That Define Us, but around halfway through the book (which is only about 110 pages long!) he transitions from giving decision making advice to giving life advice.

His argues that we often overlook the deeper implications of important decisions. We can make a 'pros and cons' list of things we like about San Francisco vs. Boston, but it's much harder to rationally answer a question like how will I feel about the person I will become if I take this new job? As he puts it, "Human beings care about more than the day-to-day pleasures and pains of daily existence. We want purpose. We want meaning. We want to belong to something larger than ourselves...who you are and how you live are more important than what you experience."

Roberts thinks that it's impossible to rationally account for these types of factors: "It’s almost silly. How do you think about what you’d give up to have a more meaningful life?" But I'm not sure I agree. Everyone does eventually make those choices, and I think that at least trying to put those ineffable factors on your pros and cons list will lead to slightly better choices.

He makes a good point about the problem of predicting what our future selves will want. (He calls it the "vampire problem"—the you of right now might be disgusted by sleeping in a casket and drinking blood, but were you to actually become a vampire, that future vampire you would be happy with their life.) When making the decision to, for example, get married, you have to try to predict what kind of person married-you would be, and what they would value in life. We tend to have trouble doing this!

The "life advice" wasn't bad, per se, it just wasn't especially new to me; I would've preferred to read another 50 pages about decision making. Here's some advice I highlighted:

Inevitably, if you see yourself as the main character of your own reality show and people around you as part of the supporting cast, you miss a big part of life and who you can be as you experience it...Part of what the ensemble mindset does is help you get over yourself. It makes you smaller, in a good way. Your ego shrinks to scale. You’re not the center of the universe.

The Truth by Neil Strauss

A fun book overall. I got more "into" reading it than I have for most books lately—it was easy to choose to read over wasting time on the computer, which isn't always the case. Maybe that's just because books about sex & relationships just tap into some very human feelings, and I don't read many of them. His story is a real "hero's journey"-type adventure, even if it's "non-fiction". I felt the tension of watching our main character to see if he would make it through the dark days and find success by the end of the book. And he's just pretty good at writing a readable, funny story, like the time he went to this, uh, spiritual orgy:

“I’d like you to now touch the source of your sacred energy and make a connection with it,” Kamala intones. I place my palm over my heart, but everyone else lays a hand over their junk. Clearly they know something I don’t.

Although my personal experience is infinitely more boring than his, I felt some parallels between his growth and mine. My relationships (to the extent they existed) at the end of my teenage years are a bit tough to look back on now. Themes included: hurting people because I didn't have the skill to communicate when I felt hurt; being selfish but only realizing how selfish I was years later; jealousy and insecurity because I lacked confidence in who I was; etc. Only in the past few years have I become able to confidently discuss my needs and (more-or-less) selflessly help my partner feel that their needs are fulfilled.

Similarly, I connected with his realization that, though we may all have our own unique "trauma" from growing up, as adults we have the opportunity to understand the way those experiences shaped us and then choose to be different. Perhaps it's not an easy path, but it's possible. We can connect as passionate and understanding adults, not just looking for the person that will fill the hole in our soul.

An Immense World by Ed Yong

I read this book because it was on many best-of-the-year lists at the end of 2022, and in my opinion those accolades were well-earned. Some books I write short reviews because they weren't that interesting; for An Immense World I'm writing a short review because it was too interesting. It is a book about animal senses, and there are so many interesting facts about animal senses. Here are a few quotes I highlighted from throughout the book:

There are animals with eyes on their genitals, ears on their knees, noses on their limbs, and tongues all over their skin.

Treehoppers communicate by sending vibrations through the plants on which they stand.

[Why do snakes flick their tongues?] It turns out that the tongue’s tips splay out at the ends of each flick and get closer at the midpoint. This motion creates two donut-shaped rings of continuously moving air that draw in odorants from the left and right sides of the snake.

The fly can tell if one antenna is just 0.1°C hotter than the other

As a fish swims, it leaves behind a hydrodynamic wake—a trail of swirling water that continues to whirl long after the animal has passed. Seals, with their sensitive whiskers, can detect and interpret these trails.

[Ever see a spider floating through the air? They fly using...electricity!] Spider silk picks up a negative charge as it leaves a spider’s body, and is repelled by the negatively charged plants on which they sit. That force, though tiny, is enough to launch the spider into the air.

If you think this stuff is as cool as I do, definitely read this book.

Playful Parenting by Lawrence Cohen

I heard of this book and picked it up because the title spoke to me (as a coach). I really liked the idea of this book—engaging with younger people through being goofy, playful, and fun. The title spoke to me when I saw it because I'd recently noticed that some of my best moments as a coach, when my players seemed to be immersed and concentrated but having lots of fun, were when we were just goofing around, playfully finding ways to challenge each other ("let's try to do this...ok, now let's try to do THIS").

The title spoke to me—but unfortunately the book itself bored me. I made it 1/4 of the way through before giving up. It was too repetitive—lots of anecdotes, all of which seemed to be variants of: there was this kid who was having trouble. I played with them to help them work through their experiences. And it didn't feel like there was any deep, unintuitive advice that needed to be shared beyond "be more playful with your kids". The anecdotes could be useful as a reference if you're having trouble figuring out how to be playful in a certain situation, but I didn't feel the need to read the rest of the book front-to-back.

A Mind for Numbers by Barbara Oakley

I've read a number of books about the science of learning. It feels important for my own growth and as a coach I want to help my players learn effectively. A Mind for Numbers might be the best of those books to recommend to a student for its straightforward advice.

Reading the book, I thought back to my own time as a college student. Would I have used the techniques she suggests if I had read this book back then? I might have...but I also might not have. Can procrastination be fixed by reading the right advice in a book? I think to some extent there weren't any shortcuts to becoming the person I am now; wisdom and patience just came as time passed and I experienced life. To give a specific example: I was too shy and uncomfortable to go to office hours to ask professors questions. Just reading in a book that doing so is the best way to learn probably wouldn't have been enough to get me there.

(Speaking of being shy and uncomfortable, I aspire to be the type of person she talks about in this quote: "One thing has surprised over the years. Some of the greatest teachers I’ve ever met told me that when they were young, they were too shy, too tongue-tied in front of audiences, and too intellectually incapable to ever dream of becoming a teacher. They were ultimately surprised to discover that the qualities they saw as disadvantages helped propel them into being the thoughtful, attentive, creative instructors and professors they became. It seemed their introversion made them more thoughtful and sensitive to others, and their humble awareness of their past failings gave them patience and kept them from becoming aloof know-it-alls.")

I won't review the book in detail since I've already written a lot about the science of learning. Here are a few quick notes:

She is a big fan of the power of writing things out by hand (although weirdly, after bringing it up a few times, she offhandedly mentions that "there is little research in this area").

I've written about the balance between persistence and taking breaks in the process of developing skills (here for example). I liked the way she put it in this quote: "persistence can sometimes be misplaced—that relentless focus on a problem blocks our ability to solve that problem. At the same time, big-picture, long-term persistence is key to success in virtually any domain. "

"Some instructors do not like to give students extra worked-out problems or old tests, as they think it makes matters too easy. But there is bountiful evidence that having these kinds of resources available helps students learn much more deeply."

I've been in and out of the habit of making to-do lists. I'd mostly thought of them as ways to (1) not forget to do things and (2) have direction so I know what to work on. She points out another benefit: "...once you make a task list, it frees working memory for problem solving."

If you want to learn how to learn effectively and get good at STEM, read the book.

Philosophy: A Complete Introduction by Sharon Kaye

A book that introduces the ideas of our most famous philosophers, using everyday language. Well, at least it tries to. There were a few points that I still found a bit confusing. I really enjoyed this book, especially the chapters on philosophers who discuss how we should live our lives. I'm less interested in reading about Plato and his Forms or what Anselm and Aquinas had to say about God.

The chapter on Jean-Paul Sartre especially impressed me. I'd his name before...but to be honest, I mostly knew his name from getting name-dropped in a Shakira song. Sartre and his work is an example of a recurring theme I noticed reading this book, which was that many of the concepts these philosophers wrote about are still relevant in our lives today, though they may go by different names. Sartre, for example, wrote about what we might call privilege, and what we decide to do in the face of the privilege we are (or aren't) born with:

Gender is not the only ‘given’ in your life. You never had the opportunity to choose many things about your identity – the language you speak, your family, the environment around you. And yet, as in the case of gender, you often have much more choice than you think. You can learn a new language, adopt a new family, or move to the other side of the world…

There is a small, unstable space right between the choice and the given. This is where authentic human existence begins, according to the French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre (1905–80)...Self-definition is the task we must all undertake in order to realize our potential, according to Sartre...As [he] puts it, freedom is what you do with what’s been done to you.

His views on romantic relationships sound like exactly what a philosopher would say (though he was also a creepy dude, apparently):

Falling in love may not exactly be a choice, but it is your choice whether or not to pursue the relationship. In a relationship, you want to become something new by uniting with the other in mind and body. The other has to be just as radically free as you are in order for you to create a partnership of mutual desire.

The problem is that radical freedom makes the unity inherently unstable. The effort to stabilize it turns desire into possessiveness and control, which in turn undermines freedom.

Nietzsche (the subject of another chapter) seems a bit dark to me, but his views on choosing your own meaning in life roughly match the way I think about things a a non-religious person:

All of our apparent achievements (one thinks, for instance, of the latest mobile phone) are really just superficial distractions from a hollow lack of substance at the centre [i.e., life is meaningless].

While it may be upsetting to come to this realization, it is also liberating. It forces one to realize that one is free to make one’s own meaning. Rather than giving up in the face of nothingness, Nietzsche transforms his nihilism into perspectivalism, arguing that, while there is no absolute truth, everyone can develop their own interpretation of the world...

If you like thinking about these kinds of things but have never really read a "philosophy book" before, this book is a solid place to start.

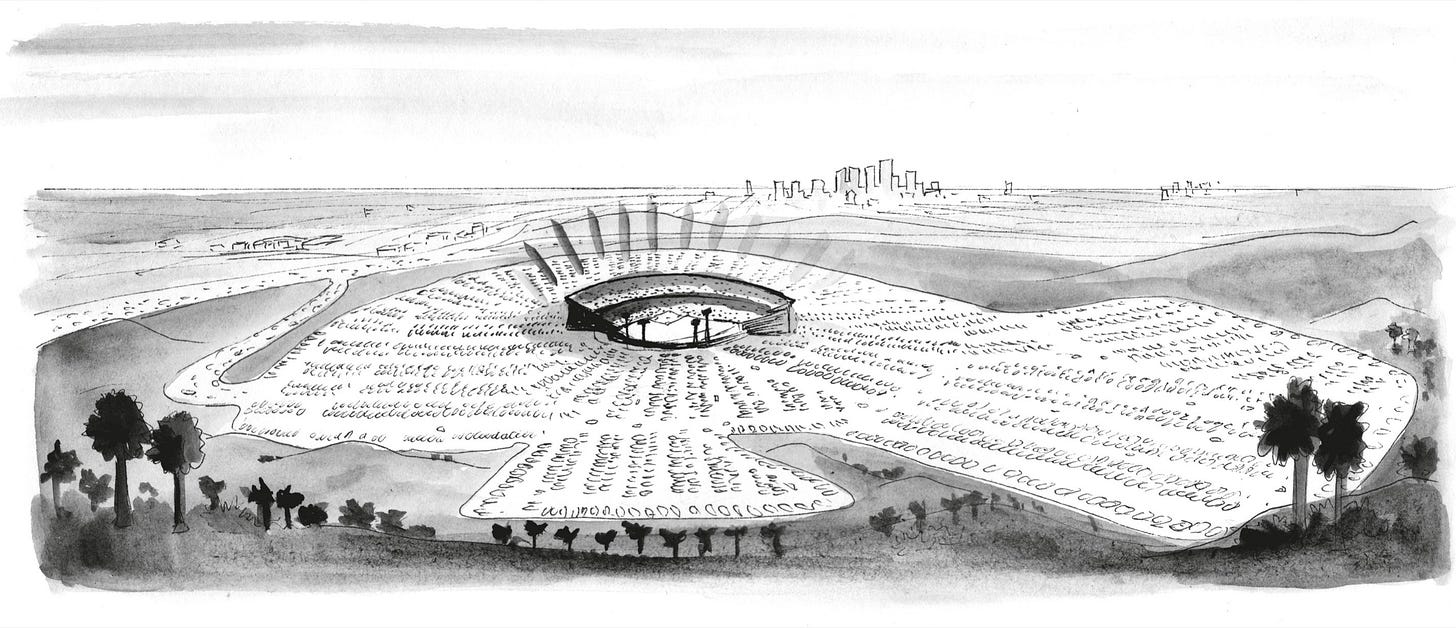

Paved Paradise by Henry Grabar

Shoup’s calculations aligned with earlier estimates that the annual American subsidy to parking was in the hundreds of billions of dollars.

New York City has perhaps the most expensive real estate in the world...and right next to that, in many places, is land that can be used for free by anyone who wants to park their car. Kind of crazy when you think about it. And by "you", I mean "me", who also had never thought about it for most of my life. Or in Boston:

The most expensive meter in Boston was $1.25 an hour; the median off-street garage downtown was $12 an hour.

In most cities, there are laws that dictate how much parking must be built with any new development (thankfully, many of these laws are being removed in recent years). But the requirements often don't even make sense:

If the Empire State Building had been built to the minimum parking requirements of a contemporary American city, for example, its surface parking lot would cover twelve whole blocks.

When LA enacted a new ordinance, "every single project that had been built under the ARO rules [the new ordinance] had constructed fewer parking spaces than would have been required by law." When Buffalo did a similar thing, "half of new major developments came with fewer spaces than had been required." One developer profiled in the book said that an apartment complex down the block from his had "to try to get about $400 a month more in rent than we have to get over here" due to all the extra space and cost involved in having more parking spots. Another developer said that:

“we determined that we owned a portfolio of twenty thousand parking spaces. On any given day, approximately half sat vacant. To put it in even greater perspective, when we calculated how much it cost us to build that, it cost us one hundred million dollars just to build the vacant ones..."

The chapter on how the city of Chicago sold their public parking to private equity was absolutely rage-inducing. Want to remove parking spaces to put in a bus lane? Or a bike lane? Have to pay the management company to make up for lost revenue. "Block party? Festival? Parade? Expect an invoice from CPM." (CPM is the company managing the parking meters)

...Motorists parking in the Loop just used disabled placards, passed through families like Cubs season tickets, which exempted them from meter payments under state law. The City of Chicago had long tolerated this practice; Chicago Parking Meters LLC did not.

...Over the first four years of the deal, CPM charged the city $73 million to make up the difference. To put it in perspective, the city was now paying CPM almost as much for apparent disabled parking fraud in one neighborhood, every year, as it had generated just a few years earlier from all thirty-six thousand parking meters.

Here's another crazy fact:

By square footage, there is more housing for each car in the United States than there is housing for each person.

Lots more like this if you want to read a book about the economics of parking.

The Case Against the Sexual Revolution by Louise Perry

[Trigger warning: mentions of rape and other sexual violence] A sort of "I'm a liberal but arguing against the liberals on this one" take on modern (American/British) sex culture. She says that, although the sexual revolution is generally seen as feminist, ironically the way things have changed ("hook-up culture") are now much closer to the average man's desires than the average woman's desires. On average, a variety of studies show that women are less interested in sexual variety than men are.

She argues that modern culture has been overly focused on consent. She's not saying that consent is bad, but that consent is not enough. Everything is permissible as long as all parties consented at the time does not work well enough. If our culture is set up in a way that people (women) essentially feel peer-pressured to consent to things they might not have been interested in doing in a different cultural setting, then we're arguably failing those people.

A similar thread exists in her discussion of sex work (where she argues against the modern liberal "sex work is work" idea). She points to a number of situations where people consented at the time but now regret taking part in sex work and felt that they were abused. (I suppose there are lots of people who regret lots of jobs they worked at, sex work or not...but it definitely feels worse when it's sex work.) Many modern left-wingers are often a bit anti-capitalist, and don't want to see everything get 'eaten by capitalism'—but then why are we letting sex get eaten by capitalism?

I agree with a lot of what she writes, but the one topic that most clashed with my experience of the world was her insistence that liberals are lenient towards pedophilia:

When you set out to break down sexual taboos, you shouldn’t be surprised when all taboos are considered fair game for breaking, including the ones you’d rather retain...Foucault and his allies...claimed that sexual desire develops earlier in some children than in others and that it is therefore possible in some cases for children to have sexual relationships with adults that are not only not traumatic but mutually enjoyable. The claim, therefore, was not that consent is unimportant but, rather, that children are sometimes capable of consenting...Their project, therefore, was not a detour from the progressive path but in fact logically in keeping with it. The principles of sexual liberalism do, I’m sorry to say, trundle inexorably towards this endpoint, whether or not we want them to.

Sure, Foucault was a "liberal", and I don't doubt that a Washington Post critic gave a positive review of the film Cuties (as she mentions later in the chapter), but my personal experience has been that everyone is very against pedophilia. And if you've followed the news in the past few years you may know that the Republican party has also been working to keep child marriage legal (for example, see here or here). To the extent that it is a phenomenon, it certainly isn't a left-wing-only phenomenon. I think she's grasping at straws on this one.

The book is (emotionally) hard-to-read at times in a way I haven't reproduced in this review. She writes about rape, porn, BDSM as a cover for male violence, and other fraught topics. Tyler Cowen said "I strongly suspect [this book] still will be read and referenced in ten or twenty years." I'm not sure I'm as impressed as he was but it gave me some things to think about.

Fiction:

Children of Time by Adrian Tchaikovsky

One of the better sci-fi books I've read in a while, though I definitely recognize that it's "my kind" of sci-fi (relatively science-based; detailed examination of how an alien society would be different from ours due to their mental and physical differences from humans).

(I don't especially like writing (or reading for that matter) reviews of fiction books. I don't want to be spoiled and also prefer not to spoil fiction I like for other people, either. But if you like hard-ish sci-fi and haven't heard of this one yet, give it a try.)

The Ministry for the Future by Kim Stanley Robinson

Famously was on Obama's reading list, but I couldn't get into it. I powered through until the end but it never gripped me. The book is a story of how humanity fights climate change over the next ~30 years. Definitely a bit bleak ("maybe peaceful times are what we’ve got now, very fucked-up peaceful times, low-intensity asymmetric insurgency terroristical climate-refugee peaceful times...") but hopeful at points as well. I had never really noticed the term "wet bulb temperature" before I read it in this book; a few weeks later I was hearing it the news due to this summer's heat wave (so, bonus points for being mildly prophetic).