[I’ve mentioned this idea before in previous articles but thought I might write a separate article to give it the focus it deserves.]

Playing defense in basketball, there’s a technique call stunting or stunt and recover. This video and this video are the first ones that come up when I search YouTube for ‘stunt and recover’. While I don’t think either of them are quite perfect for our purposes today, they roughly get the point across.

The basic idea is this: The offense would like to have open passing lanes to move the disc (let’s focus on frisbee for the moment) down the field. On defense, we’d like to deny the offense those passing lanes. Often we have a chance to do that if we sag a few steps away from our person. But this isn’t zone defense—we don’t want to leave our person too open.

So we try to get the best of both worlds—when the thrower is looking past us downfield, we attack into that passing lane to discourage the pass, i.e. we stunt towards the lane. But then once we’ve done that, we recover back towards the person we were originally guarding, so the thrower doesn’t have an easy pass there, either. Done well, one defender can help shut down multiple options near simultaneously.

I assume the word “stunt” comes from its definition of “something unusual done to attract attention”—you’re not totally committing to doing something new, you’re merely doing enough to attract the attention of the offense and use the threat of your presence to force them into a less good option (or get the steal, if the passer reads the play wrong). Then you recover back to where you were originally.

The context is slightly different in frisbee, of course. In basketball, the person with the ball can pass, but they can also attack the basket themselves via dribbling. Stunting is used both to threaten passing lanes and to help stop players who are dribbling the ball (as in the videos above). In frisbee, the thrower can’t move, so stunt-and-recover-ing only makes sense in the context of defending passing lanes.

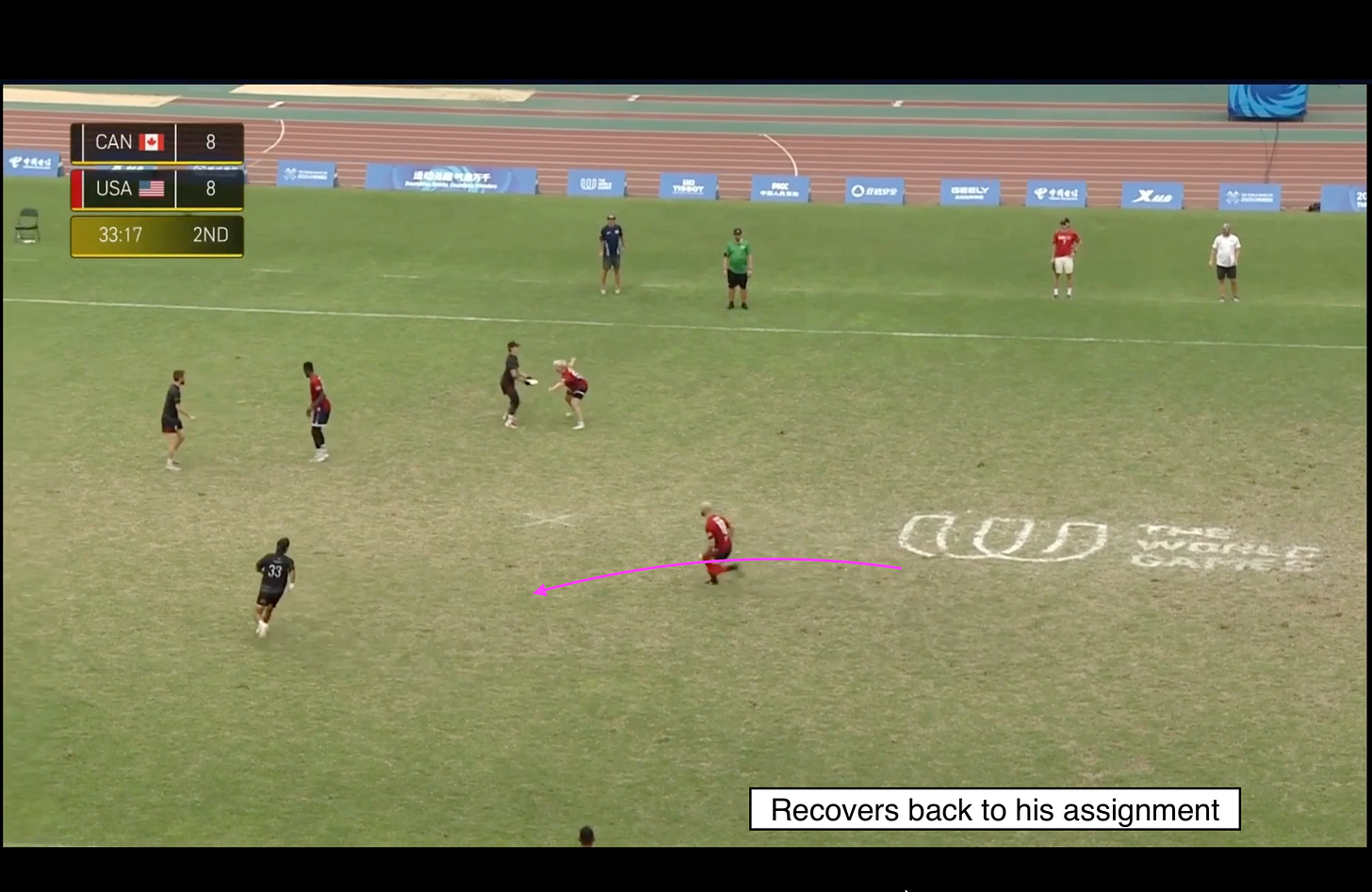

Let’s take a look at an example I highlighted very briefly in a previous article. Keep an eye on team USA’s Grant Lindsley, #10 at the bottom of the screen, who’s playing defense on Team Canada’s Marty Gallant:

With the disc on the top sideline and Gallant 10 yards downfield and across the field on the bottom sideline, Lindsley knows Gallant’s not much of an immediate threat to receive a pass. He sags off towards the center of the field.

By reading the field and the thrower’s eyes, he sees the potential for a pass through a throwing lane straight down the field. He stunts into this passing lane to discourage the throw, as Gallant jogs towards the backfield to make himself available for a swing pass:

But this is not an extended poach. Once he’s momentarily shut down that option, and he sees the thrower’s eyes start to look elsewhere, he recovers back to Gallant and is just close enough to convince the thrower not to throw that throw, either:

Team Canada takes a 5-yard loss on the next pass when they easily may have had a 15-yard gain if it weren’t for Lindsley’s play.

Basketball teams stunt and recover because they correctly understand that letting a player with the ball get into the lane a few feet from the basket is more dangerous than conceding a pass to a player 25 feet from the basket. The same logic applies in frisbee, although it often feels like many frisbee teams still don’t appreciate it—letting the offense get closer to the goal is bad. Lindsley is smart to stop a 15-yard gain and it would’ve been a smart decision even if Gallant ended up catching the next pass for a two-yard gain.

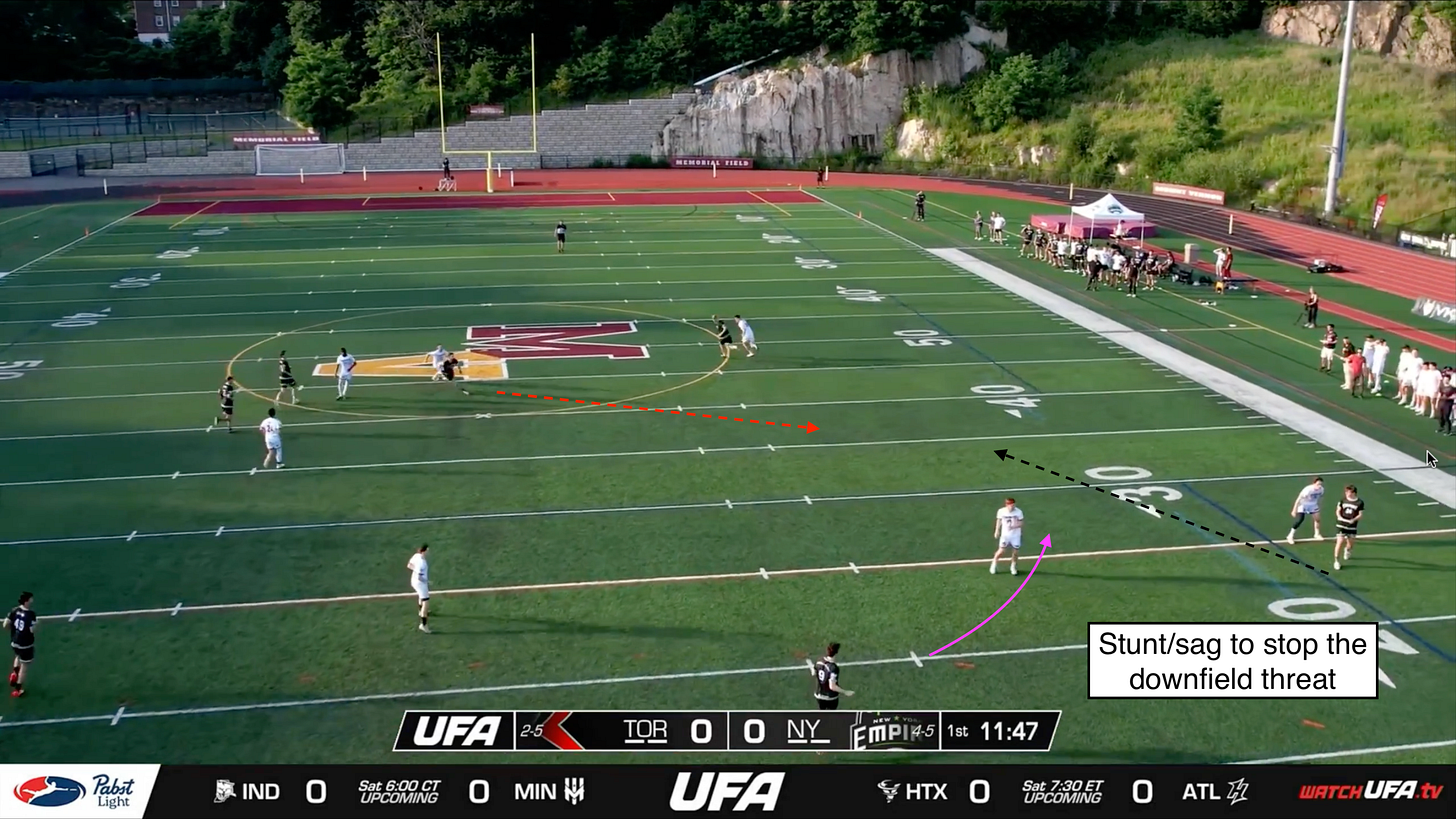

It’s also common to see stunt-and-recover tactics in zone defenses, where one defender wants to convince the thrower they’re close enough to threaten D’s on multiple receivers. Similarly, playing on the “wing” of an endzone defense in the UFA is another common spot to use stunts, as we saw in some examples from The art of beating the help defense back to the second option. Here’s another clip I found of endzone wing defender help and recover:

Note also that the assist thrown towards the top of the screen may have been averted if the defender there had stunted more heavily.

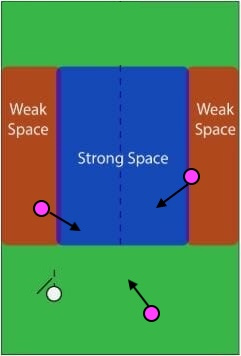

Generally speaking, it’s typical to stunt towards strong spaces when we’re guarding players in weak spaces (see Joe Marmerstein’s article here). Or to put it another way, stunt away from less threatening areas, and stunt towards bigger threats. (The variant we saw in the last clip was perhaps “stunt to stop easy throws, and force harder throws”.)

That’s why I really like to stunt and recover as a handler defender—who cares if I give up a yardage-losing reset pass to the handler I’m guarding, if I can successfully stop a downfield pass from going off? Gaining yards is (generally) a bigger threat to the defense’s success rate than losing yards. (Especially early in the stall count.)

This following example is perhaps more of a simple “sag the lane” than it is a fully dynamic “stunt and recover”—the idea is basically the same but it might be marginally more effective if the Toronto defender had left the lane slightly more open to tempt the thrower to keep looking downfield:

You might say there’s a spectrum of “stunt and recover” tactics—an early and obvious stunt can be used to discourage a throw, while a smaller, subtler stunt baits a throw.

Many of the arguments I laid out in Why you shouldn’t always play tight defense also apply to why the stunt and recover is effective. Lindsley’s stunt puts just a little more uncertainty in the thrower’s mind—it’s a little harder to tell whether they actually have enough room to get the throw off. Add that additional marginal amount of confusion across the scope of a game or an entire tournament, and throwers for the other team will have more decision-making errors. Instead of just letting the offense have their first option, force them into their second or third option, over and over again.

I truly believe defensive strategy in frisbee won’t have matured until every player knows how to stunt and recover and is doing it all the time. This shouldn’t be a skill exclusive to Grant Lindsley-level players. Look at the basketball video I linked above—the NBA makes videos showing early high schoolers learning to stunt and recover. If 14 year-olds can learn this skill in basketball, there’s no reason every player in college and club frisbee shouldn’t be able to master it, as well.

You might be shouting to the void, but you are correct haha. Stunting is just a defensive feint, like a cutter jab step. Weird how every cutter in the world would be crazy not to jab step, but defenses are like nah no jab step for me thats weird.

I just want to say thank you for sharing so much information in these little articles. I’m a dude in rural PA just trying to learn and you’ve shared a ton of helpful info that I don’t know how I’d have figured out otherwise.