[Warning: This is a long one! But hopefully full of lots of interesting information.]

The blog Slime Mold Time Mold ("SMTM") recently published a series of articles arguing that America's obesity crisis is due to human exposure to obesity-inducing chemicals. The first post can be found here. I'd like to offer a few thoughts, criticisms, and rebuttals. Parts of this post will be bringing together criticisms I've seen elsewhere into one post, and other sections will offer some criticisms that I haven't already seen elsewhere.

In praise of the series

In short, SMTM says that there are chemicals that reliably cause people to gain weight, and our exposure to those chemicals is much higher than it used to be. It's a really interesting hypothesis that I hadn't heard before and I think the core arguments are pretty compelling. For example, take livestock antibiotics:

In meat animals, antibiotics often lead to weight gain, sometimes as high as 40% weight gain compared to control...

Or lithium:

While [Lithium] occurs naturally in small concentrations in groundwater, human activity might have led to serious increases over the past few decades.

Unlike the other contaminants we’ve reviewed, we don’t need to spend any time convincing you that lithium makes people gain weight: it does. Almost everyone who takes lithium at therapeutic levels gains some weight. About half of them report serious weight gain, on average 22 lbs (10kg), and about 20% of patients gain more than that.

This series has convinced me that part of our obesity epidemic is due to exposure to chemicals that "cause" weight gain.

A second important part of this theory is the idea that weight (or specifically, fat stores) is regulated in large part by the brain. I wanted to introduce this concept as it'll come up a few more times in my thoughts below. This is the "lipostat":

The human body has a lipostat (from the Greek lipos, meaning fat). Evolution and environmental factors set body fatness to some range — perhaps a BMI of around 23. The lipostat detects how much fat is stored and takes action to drive body fatness to the set point of a BMI of 23....

According to this theory, people become obese because something has gone wrong with the lipostat...

The lipostat model is supported by more than a hundred years of evidence...

Modern neuroscience and medical review articles (those are three separate links) overwhelmingly support this homeostatic explanation. In animals and humans, brain damage to the implicated areas leads to overeating and eventual obesity. These systems are well-understood enough that by targeting certain neurons you can cure or cause obesity in mice...the few weight-loss drugs approved by the FDA largely act on the brain...

Those "actions" mentioned in the first quoted paragraph mean, as I understand it, things like "feeling more hungry" or "feeling less interested in activity" or "fidgeting a lot".

Now, let me point out some areas where I'm not convinced by these essays. Here's where we're going in this post:

A. Part of the epidemic or all of it?

B. Ignoring "common sense" leads to new mysteries

C. Does it matter that 50% of Americans meet activity guidelines?

D. Diet studies are for short time periods

E. Obesity and Trauma

F. Obesity and social communicability

G. Is food really not that much tastier?

H. Food is less nutritious than it used to be

I. Better at keeping obese people alive?

J. A decrease in people smoking

K. People are less obese in cities

L. Other weird environmental effects

M. Some Closing Thoughts

Conclusion: So what is causing the obesity epidemic?

A. Intro: Part of the epidemic or all of it?

Many of the later points I'll raise are relative to this first point. To say that chemical exposure is one of the reasons for our obesity epidemic is one thing, but SMTM goes beyond that. They say:

Only one theory can account for all of the available evidence: the obesity epidemic is caused by one or more environmental contaminants, compounds in our water, food, air, at our jobs and in our homes, that change how our bodies regulate weight.

These contaminants are the only cause of the obesity epidemic, and the worldwide increase in obesity rates since 1980 is entirely attributable to their effects. [emphasis theirs]

In my opinion, they present solid evidence that environmental contaminants are part of the picture of the obesity epidemic.

SMTM and I both read Scott Alexander's blog. And I think what I (and many other readers) like about Scott Alexander is his ability to say "X is an important factor, but there's also Y and Z, and these studies are not as good as they could be, and it's hard for me to say for certain, and I'd love to see people perform studies A, B, C, and D to help us sort this out." I agree with SMTM that "X" (environmental contaminants) is an important factor, but I'm not convinced, as they are, that "Y" and "Z" don't have roles to play, too. I want to bring a bit of that in this article.

SMTM does admit one other possible cause of obesity: genetics. In Part IV, they say:

A 2012 meta-analysis of 115 studies concluded that around 75% of individual difference in BMI is genetic...

So, SMTM argues that apart from the 75% of the variance in BMI that is genetic, the other 25% is entirely due to environmental contaminants.

The following sections will discuss further what I think those other causes are and where SMTM's analysis seems, to me, to be lacking. I'll essentially argue in favor of not completely throwing out the "conventional wisdom": that diet and exercise and general lifestyle factors can have an effect on an individual's weight.

B. Ignoring "common sense" leads to new mysteries

SMTM points out that there are some interesting "mysteries" about the obesity epidemic: people who live at high altitudes are less obese, there are hunter-gatherer tribes that are not obese but eat lots of sugar, etc. One thing, they say, that would solve many of these mysteries is the chemical contaminant argument.

However, it seems to me that saying "contaminants are the only cause of the obesity epidemic" generates new mysteries. Here are some new mysteries that we'd have to be able to explain under the environmental contaminant hypothesis:

Why is the obesity rate in my local ultimate frisbee league so much lower than in the United States as a whole?

Why is the obesity rate in the semi-pro ultimate frisbee league even lower than that?

Why is the obesity rate so low among the bike commuters I know?

Why do all the people on weight loss subreddits (e.g. progresspics) say they either used gastric bypass surgery or diet and exercise? Where are the people losing weights when they accidentally make a lifestyle change that results in less contaminants?

In short, is it really possible that environmental contaminants can be the "only cause" of the obesity epidemic when it seems so obvious that people who are more active are less obese? There could be "selection effects" (Only people who are already non-obese choose to commute by bike or play frisbee), but my intuition is that this isn't the only reason for the differences in obesity rates. There are a number of other "mysteries" that would be need to be solved by an environmental-contaminant-only theory that are discussed in further detail below.

C. Does it matter that 50% of Americans meet activity guidelines?

SMTM points out that more Americans than previously are meeting certain activity levels, but obesity is still high and rising. This is used as evidence that "exercise [doesn't] explain modern levels of obesity."

Commenter gleamingecho replied with a Department of Health and Human Services source from 2019 that says, in fact, it's not true that more than 50% of Americans are meeting activity guidelines:

Although the latest information shows some improvements in physical activity levels among American adults, only 26 percent of men, 19 percent of women, and 20 percent of adolescents report sufficient activity to meet the relevant aerobic and muscle-strengthening guidelines

But SMTM's post had a source, too, from the CDC, showing that in 2017 over 50% of Americans did meet the "2008 federal physical activity guidelines for aerobic activity through leisure-time aerobic activity".

So what's going on here? The 2008 federal physical activity guidelines say:

adults should do at least 150 minutes (2 hours and 30 minutes) a week of moderate-intensity or equivalent...

Adults should also do muscle-strengthening activities that are moderate or high intensity and involve all major muscle groups on 2 or more days a week...

As far as I can tell, the difference between this "over 50%" and "only 26 percent of men and 19 percent of women" is this: one source is the "Adults Who Met the Aerobic and Muscle-Strengthening Guidelines", while SMTM's source is for "aerobic activity" only. In other words, many Americans are not doing enough muscle-strengthening exercises!

Lack of muscle has been specifically pointed out by others as a reason for people having trouble staying healthy. Is our obesity crisis is a crisis of people not lifting weights enough? This fits well with the viral news story from a few years ago that American men have weaker grip strength than 30 years ago! I recently read in Richard Meadows's book, Optionality:

...staying in shape is much easier than the hustle-porn #inspo posts would lead you to believe...Personally, I eat some kind of junk food pretty much every day, rarely do more than three hours of exercise a week, and haven't counted calories in years. But I've never been fitter!...

If you can build up a little strength and muscle mass, you kickstart a positive feedback loop which makes life easier on every possible dimension...The more lean mass you have, the higher your metabolic rate. Muscles are expensive to maintain, and they’re burning calories all the time. Even when you’re sitting on your butt! My basal metabolic rate ranges as far as 400 calories from baseline, depending on how much lean weight I’m carrying...

The underappreciated strategy for getting enough micronutrients is to eat more food. If you’re taking in 3000 calories and aren’t a total slob, you’ll be over the recommended daily intake for most-everything without even trying. By contrast, someone on a measly 1300 calories has to be extra careful to cover all the nutritional bases, which makes an already miserable diet even more restrictive...

Muscle mass burns calories. And while ~50% Americans are meeting aerobic activity guidelines, many fewer are meeting muscle strengthening guidelines. And muscle mass has an important effect on our metabolism.

...

Before I got distracted researching that discrepancy, I actually started this section planning to say something totally different about Americans meeting activity guidelines. Here's a couple other reasons why 50% of Americans meeting activity guidelines doesn't convince me that activity isn't important for weight:

The obesity rate is ~42%, and there's ~52% of Americans meeting aerobic activity guidelines. It's totally possible that these two groups just don't overlap! If the obesity rate ever passes the rate of Americans meeting activity guidelines, I'll update my opinion.

Just because this is a guideline for health doesn't mean that it's a guideline for weight loss. It could be that these guidelines are sufficient to maintain weight but not to lose weight.

Finally, the data is based on surveys (" household interviews of a sample of the civilian noninstitutionalized population") and activity levels can be measured in relative terms. Since obese people have more weight to carry around, activities are relatively harder, and they may not be getting enough activity in an absolute (instead of relative) sense compared to lighter people.

Let me dig into that second point: are these guidelines reasonable, anyway? In Exercised, Daniel Lieberman shares data on hunter-gatherer activity levels:

Large samples of Americans asked to wear heart rate monitors indicate that a typical adult engages in about five and a half hours of light activity, just twenty minutes of moderate activity, and less than one minute of vigorous activity [per day]. In contrast, a typical Hadza adult spends nearly four hours doing light activities, two hours doing moderate-intensity activities, and twenty minutes doing vigorous activities.

Note that the 20 minutes per day is 140 minutes per week, exactly in line with the data above that the average American is just-about meeting the activity guidelines. But hunter-gatherer populations are meeting those moderate-intensity activity guidelines, 5 times over!

Overall, I'm not particularly convinced of anything from the fact that over 50% of Americans are meeting aerobic activity guidelines. If anything, it's increased my conviction that muscle-strengthening is important for healthy adults.

D. Diet studies are for short time periods

I'm not sure how convinced I'll ever be by an overfeeding study.

SMTM uses the results of overfeeding studies (the result is that people generally gain weight, but then almost always return back to their original weight without much effort) to make the point that eating more doesn't make people fat. However, look at how long these studies last (from Part II): "2 weeks", "21 days", "22 days", "10 weeks", and "a little over three months". But of course, to the extent that some of us think the obesity crisis is caused partly by people eating too much, that eating has been going on for a decade or more. My hypothesis is that the lipostat can be influenced by overeating, but that it takes longer than "three months" to do so. I'm not convinced by a three month overfeeding study that a decade of overfeeding won't have an effect on the lipostat.

In Part II, SMTM used this study below to argue that overfeeding doesn't lead to weight gain:

Researchers recruited inmates from the Vermont State Prison, all at a healthy weight, and assigned some of them to eat enormous amounts of food every day for a little over three months. How big were these meals? The original paper doesn’t say, but later reports state that some of the prisoners were eating 10,000 calories per day.

But in Part VI, SMTM says this about studies of PFAS:

Maybe PTFE really is that inert...Either way, the safety research on these substances is pretty ridiculous. Usually the exposure period is very short and the dose is extremely high. [emphasis mine]

Earlier in the article, they point out that PFAS stay in the body for a number of years:

A CDC report from 2015 found PFAS in the blood of 97% of Americans, and a 2019 NRDC report found that the half-life of PFAS in the human body is on the order of years. They estimate 2.3 – 3.8 years for PFOA, 5.4 years for PFOS, 8.5 years for PFHxS, and 2.5 – 4.3 years for PFNA.

I think it's reasonable to argue that we need to apply the same standards to overfeeding studies that we do to studies of PFAS! Many bodily changes happen on a timescale longer than three months. I imagine an overfeeding experiment lasting a decade-plus is never going to happen, for ethical reasons, and that does make it harder for us to answer this question.

The diet studies that SMTM mentions span a larger time period: 1.5-2 years. So I do think this provides some evidence that obesity won't be cured just by Americans switching to eating the "right" foods. My model of this is that some of the factors that affect lipostat are like a ratchet: going up isn't the same as going back down. I do think there are "right" diets that make it easier for a person to maintain their weight and "wrong" diets that often lead to weight gain, but that doesn't mean that switching an obese person to the "right" diet will cause them to lose lots of weight. Poor diet can still be a cause of obesity, even if proper diet isn't a consistent path to weight loss! More on diet coming below.

E. Obesity and Trauma

Many studies have been done on the relationship between adult obesity and childhood trauma. To quote from a blog post that showed up in the first few search results,

Researchers at the Karolinska Institutet in Sweden recently conducted a meta-analysis of previous studies, which included a total of 112,000 participants, and concluded that being subjected to abuse during childhood leads to a marked increase in the risk of developing obesity as an adult...

A 2013 analysis of 57,000 women found that those who experienced physical or sexual abuse as children were twice as likely to be addicted to food than those who did not.

This result is hard to square with the environmental contamination theory. If SMTM has a convincing explanation for how this is all caused by contaminants, I would be very impressed!

My girlfriend pointed out that, more generally, there's a well-known link between obesity and stress:

Many pathways connect stress and obesity...stress interferes with cognitive processes such as executive function and self-regulation. Second, stress can affect behavior by inducing overeating and consumption of foods that are high in calories, fat, or sugar; by decreasing physical activity; and by shortening sleep. Third, stress triggers physiological changes in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, reward processing in the brain, and possibly the gut microbiome. Finally, stress can stimulate production of biochemical hormones and peptides such as leptin, ghrelin, and neuropeptide Y.

And it has been shown that stress can predict obesity and is not just correlated with it: " Prolonged [financial stress] was a strong predictor of subsequent obesity..."

Finally, there's at least some evidence that people are more stressed than they used to be. The results of this research just happen to line up with one of the "mysteries" that SMTM pointed out: people getting fatter as they get older, when that wasn't the case a century ago. The researcher is quoted, "it was people about 50 to 64 who were the most stressed out. That stood out, shockingly so."

Finally, somewhere in the intersection between "stress causes obesity" and "tastier foods cause obesity" is this study which claims that "An increasing number of prospective studies have shown that emotional eating predicts subsequent weight gain in adults."

Although there's evidence trauma leads to obesity, I agree that trauma didn't cause the obesity epidemic, unless there was also a trauma epidemic. Stress and emotional eating, however, do show some signs of having increased in the past ~50 years, and so could be playing a role in the obesity epidemic. And all of these connections with obesity are a strong hint that the lipostat can be changed by things other than just environmental contaminants.

F. Obesity and Social Communicability

An analysis based on the famous Framingham Heart Study suggests that obesity is a communicable disease: if a friend or other close relation becomes obese, you'll be more likely to become obese yourself:

A person's chances of becoming obese increased by 57% (95% confidence interval [CI], 6 to 123) if he or she had a friend who became obese in a given interval. Among pairs of adult siblings, if one sibling became obese, the chance that the other would become obese increased by 40% (95% CI, 21 to 60)... These effects were not seen among neighbors in the immediate geographic location.

In other words, our bodies can be affected by the culture around us: when our friends look a certain way and have certain habits, we are going to be slightly drawn towards that culture ourselves.

This is an interesting result — it's not entirely clear how it complements or conflicts with the environmental contamination hypothesis. The authors say the effects were not seen among neighbors in the immediate location, and that it doesn't matter how far away the obese friend lives for this effect to occur: "geographic distance did not modify the intensity of the effect of the [friend's] obesity on the [individual being analyzed]."

To me, this seems like a strike against the environmental contaminant theory, especially the version of the theory that says these contaminants are coming to us through groundwater. I think it's safe to assume that neighbors are being exposed to the same contaminants in water.

But there could still be room for the environmental contaminant theory. Perhaps we're more likely to become friends with people we work with, and SMTM has suggested that one possible source of exposure to contaminants is through employment. I read through the paper quickly and didn't see any evidence that the authors controlled for whether the friends being studied work together or not.

While neighbors are probably drinking the same water (or maybe not! Maybe if your friend drills a well, you're more likely to do so, too), it's possible that there are other sources of contaminants that friends could be exposed to when spending time together.

More careful follow-up could help tease apart whether there are different effects at work here. (This study has been cited 6000+ times, so lots of follow-up has been done...but it's not so easy to figure out if they've done the analysis that would help us here!)

G. Is food really not that much tastier?

SMTM argues against the idea that food is tastier, more appealing, and more available than it used to be (again, comparing 2020 to ~1970):

This wasn’t a steady, gentle trend as food got better, or diets got worse. People had access to plenty of delicious, high-calorie foods back in 1965. Doritos were invented in 1966, Twinkies in 1930, Oreos in 1912, and Coca-Cola all the way back in 1886. So what changed in 1980 [when obesity rates suddenly starting rising sharply]?

There are a few reasons I don't think this is a convincing rebuttal to the idea that improved food taste/availability has no effect on obesity rates.

First, the claim that these specific foods haven't "changed" isn't correct. While these foods have existed for many years, the recipe has changed. The answer to this Quora question points out that the recipe for Oreos must have changed since 1912, since High-Fructose Corn Syrup, Thiamine Mononitrate, and Riboflavin didn't exist in 1912. This AP article confirms that the recipes for Coca-Cola and Pepsi have changed:

In the book "Secret Formula," which was published in 1994...reporter Frederick Allen noted that multiple changes were made to the formula over the years...the formula for Pepsi was changed to make it sweeter in 1931 by the company's new owner, who didn't like the taste...

In the 1980s, Coca-Cola and PepsiCo both switched from sugar to high-fructose corn syrup, a cheaper sweetener.

Likewise, the Twinkies recipe has changed as well:

A representative for Hostess, Hannah Arnold, said in an email that Twinkies today are "remarkably close to the original recipe," noting that the first three ingredients are still enriched flour, water and sugar.

Yet a box of Twinkies now lists more than 25 ingredients and has a shelf-life of 45 days, almost three weeks longer than the 26 days from just a year ago. That suggests the ingredients have been tinkered with, to say the least, since they were created in 1930.

"When Twinkies first came out they were largely made from fresh ingredients," notes Steve Ettlinger...

These are not the same foods they were when they were invented ~100 years ago.

Second, there are a few areas of improvement in food taste that don't even show up on a list of ingredients. One is in flavor science: an ingredients list may say "natural flavors", but we don't know what those flavors are or if they have changed compared to an older version of a food product. I've had trouble finding good information about the flavor industry, but it has certainly grown over the last 50 years. And they are spending billions of dollars a year trying to make our food tastier:

In a fascinating 2011 interview that aired on 60 Minutes, scientists from Givaudan, one of the aforementioned power players in the food flavoring world, admitted their number one goal when creating flavors was to make them addictive!

And these natural flavors are incredibly prevalent:

natural flavors...are currently the fourth most common food ingredient listed on food labels...

I can only assume that all of this research and investment is succeeding at making our food tastier.

Another area of improvement in taste is in the texture of food. This has been written about more and more in the past few years:

Calling texture “the backbone of many product formulations,” Nieto says that texture is playing more pronounced roles in product development as the trends around plant-based eating and clean, simple, and convenient foods continue to evolve. “Creating new and just-right textures can be a new territory for product formulators trying to ensure the best eating experience for consumers in changing segments,” she says.

Without necessarily changing the ingredients in ice cream, making it with liquid nitrogen creates a tastier product. Our crispy foods are now perfectly crispy; our creamy foods are now perfectly creamy.

SMTM says there were "plenty" of delicious foods in 1970, but, again, it isn't quite that simple. This MarketWatch article, interviewing the author of a book on grocery stores, says that:

We’ve never had more food or greater diversity...There used to be, as late as the 1990s, 7,000 items in a grocery store, and now it’s 40,000 to 50,000.

People get bored eating the same thing over and over again. More options means more novelty and (marginally) more desire to keep eating. More options also means that there's something for everyone's taste. Maybe you don't like Oreos that much. Fifty years ago, you'd be out of luck (so to speak), but today there's five other sweet things that perfectly fit your taste buds' unique preference.

A Reddit comment also pointed me to this study showing that people gained more weight on an "ultra-processed" diet, and the reason was that they chose to eat more. Here's the key quote:

On the ultra-processed diet, people ate about 500 calories more per day than they did on the unprocessed diet.

SMTM points out that calorie consumption has increased since 1970, but that this doesn't tell us much, since the body needs more daily energy when it weighs more:

This is something of a chicken and the egg problem. We could weigh more because we eat more calories, but we could also eat more calories because we weigh more, and we need to eat more calories to continue functioning at that weight.

This study, however, shows that there might be answers to this chicken and egg question: at least in this experiment, people chose to eat more food when tastier food was available.

One final way that food is more available than it used to be: we've gotten richer and so have more disposable income, than 40 or 50 years ago. So relatively speaking, food is cheaper as a percent of our disposable income.

All of these factors add up to a clear conclusion that it is a bit harder than it used to be to avoid eating tasty food.

SMTM also responds to the "food is tastier" hypothesis in this Reddit thread, focusing on how lab animals are also becoming more obese:

the case with lab animals is better documented, and for lab animals, researchers try their best to give the animals constant living conditions and diets. A good source in our opinion is a paper called Canaries in the Coal Mine. Authors include primate research specialists like Joseph Kemnitz and obesity specialists like David B. Allison. This is how they describe their findings:

...laboratory animals...are on highly controlled diets, which have varied minimally over the last several decades. These animals are typically fed ad libitum, so if weight increases are attributable to increases in food consumption (which is possible), it is difficult to understand why animals in controlled environments on diets of constant composition are consuming more food today than in past decades.

I agree that this is quite the mystery. Looking at the paper, overall it seems that non-human animal weight gain is happening in many cases just as fast or faster than in humans — very roughly 5% per decade. To be honest, I was hoping that lab animals would be getting fatter more slowly than humans, so I could say, "see, just like I said, contamination is one of many sources of obesity!" For me, this is one of the more convincing pieces of evidence in favor of the environmental contamination hypothesis.

H. Food is less nutritious than it used to be

There's evidence that a lot of food is less nutritious than it used to be. One aspect of this is new breeds of grain and vegetable that are optimized for both consumer preferences (we like sweet things) and for durability and stability on the supermarket shelves (food that doesn't spoil easily is preferred by the food industry). For example, here's some discussion of corn from the book Eating On The Wild Side:

The ancestor of our modern corn is a grass plant called teosinte that is native to central Mexico. Its kernels are about 30 percent protein and 2 percent sugar. Old-fashioned sweet corn is 4 percent protein and 10 percent sugar. Some of the newest varieties of supersweet corn are as high as 40 percent sugar.

This is not just due to comparing pre-historical times to now: the change happened in the middle of the 20th century:

In 1961, Laughnan began to market the first of his supersweet corn varieties—Illini Xtra-Sweet, along with an extra-sweet version of the popular Golden Cross Bantam.

At the same time that the sugar content was increasing, micronutrients were being lost. Here's further discussion, this time of potatoes, from the same book:

The Purple Peruvian potato is a small knobby potato that has been cultivated for several thousand years...Its abundance of anthocyanins makes it one of the most nutritious of all varieties. On an ounce-per-ounce basis, it has twenty-eight times more bionutrients than our most popular potato, the Russet Burbank, and 166 times more than the Kennebec white potato.

Here's some history of the Russet Burbank from Wikipedia:

Russet Burbank was not initially popular, accounting for only 4% of potatoes in the US in 1930. The introduction of irrigation in Idaho increased its popularity as growers found it produced large potatoes that were easily marketed as baking potatoes... By the 2010s, Russet Burbank accounted for 70% of the processed potato market in North America, and over 40% of the potato growing area in the US.

It's another change that happened in the middle of the 20th century! Yes, Americans were eating "corn" and "potatoes" in 1900, and not getting fat; and they were eating "corn" and "potatoes" in 2010 and getting fat at record numbers. SMTM says that this is proof that corn and potatoes (or, diet more generally) can't be the reason for the obesity epidemic, but the USDA data doesn't account for how corn and potatoes have changed in those 100+ years.

Let me bring back the discussion of Twinkies from the previous section. A quote I read there reminded me of a fact I'd read long ago. The Twinkie historian said that "when Twinkies first came out they were largely made from fresh ingredients". Why is this important? Well, supposedly flour quickly loses much of its vitamin content after being ground. Here's the relevant quote from the book The Third Plate:

The natural oils in the wheat germ are what imbue it with flavor, but they have a short shelf life. Seriously short—they begin to spoil as soon as they are released. Which means that in order to capture the grain’s aroma, the flour has to be fresh. That’s true for nutrients as well—flour has been shown to lose almost half its nutrients within just twenty-four hours of milling.

This changed happened just a little earlier than some of the changes discussed above, with "shelf-stable flour" becoming prevalent after the invention of the roller mill:

Gristmills dotted the countryside—one for every seven hundred Americans in 1840. Once ground, flour had a shelf life of only about one week...

The roller mill appeared in the late 1800s [Wikipedia says 1874]...Whereas stone mills had crushed the tiny germ, releasing oils that would turn the flour rancid within days, roller mills separated the germ and bran from the endosperm. This new ability to isolate the endosperm allowed for the production of shelf-stable white flour...

So, depending on how quickly they spread, I'd guess that many people around the year 1900 were still eating fresh, stone-ground flour, but when Twinkies were invented in 1930 they were probably made with flour from roller mills.

In researching "Canaries in the coal mine", the paper mentioned above about weight gain in animals, I found yet another source of reduced nutrients in our food: global warming! This paper reports that elevated concentrations of carbon dioxide directly reduce the amount of minerals in the plant life that we eat. From the abstract:

...elevated concentrations of atmospheric carbon dioxide reduce protein and nitrogen concentrations, and can increase the total non-structural carbohydrates (mainly starch, sugars) [in rice and wheat]...This study shows that [elevated atmospheric CO2] reduces the overall mineral concentrations... in [rice and wheat] plants.

So, it's possible that not only are plants becoming less nutritious as we develop new strains, but even plants of the same cultivar are becoming less nutritious than they used to be due to atmospheric CO2.

SMTM has convinced me that environmental chemicals like lithium or PFAS can affect the lipostat, but why wouldn't the lipostat also respond to the levels of various nutrients? If we need more calories to get the same amount of micronutrients from our food, it's reasonable that we feel the need to eat more. In fact, it seems more reasonable that the lipostat, as a part of our evolved bodies, would be affected by levels of the nutrients that have since ancient times been critical to sustaining life; evolutionarily there would be no reason for the lipostat to respond to man-made substances like PFAS.

I. Better at keeping obese people alive?

Marginal Revolution commenter dan1111 says:

...we are getting a lot better at keeping obese people alive. Treatment for diseases associated with obesity, such as heart disease and diabetes, has improved a lot since 1980. This would contribute to an upward trend in measured obesity rates, even if the incidence of obesity was not higher.

This seems like a reasonable explanation. However, as commenter Todd K points out, the obesity rate in children has also gone from 6% in 1980 to 20% in 2018 (Link). This can't be explained by doing a better job of keeping obese children alive (since children aren't dying from obesity). But 20% is still only half of the adult obesity rate.

The best way to solve this problem would be to find life expectancy data for obese people over time — what is the life expectancy of an obese 40 year old man in 1890 vs 1960 vs 2020? I did a quick search and wasn't able to find any data about changes in life expectancy for obese people.

This could also go towards explaining the "mystery" that SMTM points out in Part I: that in the past, people got slightly leaner as they got older, but nowadays, people get heavier as they age. They say:

Common wisdom today tells us that we get heavier as we get older. But historically, this wasn’t true. In the past, most people got slightly leaner as they got older. Those Civil War veterans we mentioned above had an average BMI of 23.2 in their 40s and 22.9 in their 60’s. In their 40’s, 3.7% were obese, compared to 2.9% in their 60s. We see the same pattern in data from 1976-1980: people in their 60s had slightly lower BMIs and were slightly less likely to be obese than people in their 40s (See the table below). It isn’t until the 1980s that we start to see this trend reverse...

In comparison, middle-aged white men in the year 2000 had an average BMI of around 28. About 24% were obese in early middle age, increasing to 41% by the time the men were in their 60s.

From what I can tell of this Civil War veteran study, it's consistent with the hypothesis that the obese ones were just dying earlier, not losing weight as they age — the data is a snapshot in time, so only people who were currently alive were examined.

Although I can't find great data to support it, I do think better medical care for obese people is one reason obesity rates are rising.

J. A decrease in people smoking

(An issue raised, for example, in this comment.)

It would be weird to say that "the obesity crisis is caused by people not smoking cigarettes". And, while usually I've phrased this post as discussing "causes of the obesity crisis", what's really under discussion is "the difference between obesity rates in 1970 and 2020."

It seems clear that one of those causes is the reduction in the percentage of Americans who smoke. The American Lung Association says that in 1970, 37.4% of adults smoked, while in 2018, 13.7% of adults smoked cigarettes. There are very roughly 80 million less Americans smoking than there would be if the smoking rates of 1970 were extant today.

Nicotine has the effect of suppressing appetite and causing people to weigh less (Wiki - Nicotine, Wiki - Cigarette smoking for weight loss). The Wikipedia article says simply, "Nicotine decreases hunger and food consumption." This paper estimates "that quitting smoking leads to an average long- run weight gain of 1.8-1.9 BMI units, or 11-12 pounds at the average height. These results imply that the drop in smoking in recent decades explains 14% of the concurrent rise in obesity."

Perhaps nicotine could itself be considered an "environmental contaminant", and it also works to reduce weight through interaction with our brain. In that sense, it's already part of SMTM's hypothesis that obesity is caused by environmental contaminants that mess with our "lipostat". But this is a contaminant that lowers our lipostat, and we just happen to be removing this contaminant from our environment in the past 50 years.

K. People are less obese in cities

A recent article on Works in Progress pointed out that the obesity rate in Manhattan, one of the few places in the US where it is dense enough that many people travel without private vehicles, is extremely low — about half of the rate for the US as a whole.

The more I thought about and researched this, the more interesting I found it. New York City's water comes from upstate — from Westchester County and the Catskill Mountains. But, Manhattan has the lowest obesity of any county in New York, by far:

So I think this is a strong challenge to any water contamination theory. Manhattan has noticeably lower obesity than areas upstate that it shares a source (I assume?) of drinking water with.

In the course of my research into New York City obesity rates, I also found this set of slides that says the obesity rate in 2007 among the ~200,000 residents of the Upper East Side was 8% — one quarter of the obesity rate in the whole United States at the time. Is it really possible that the Upper East Side is the least contaminated part of the country? Why does it only have 1/3 the obesity of other areas in New York City, when all of NYC has "clean" water from upstate? (The slide cites "Olson et al., 2007", which I was unable to find in a quick Google Scholar search, so I'm not super confident about this data point).

Another branch of my research led me to this NY Times article, which points to literature that shows:

"even when adjusting for poverty and race, at least three factors are associated with lowering obesity: proximity to supermarkets and groceries where fresh produce is sold; proximity to parks; and access to public transportation"

This is pretty much the "conventional wisdom": healthy foods and activity lower obesity rates. People walk more when they walk to get places instead of driving their car everywhere. (Side note, the same author has a study that "A higher homicide rate (at the 75th vs 25th percentile) was associated with a 22% higher prevalence of obesity...". That's an interesting one!)

Overall, there are a number of interesting quirks of New York City's obesity prevalence that cast doubt on the environmental-contaminant-only hypothesis.

...

After I'd written this, SMTM posted a new article suggesting that one reason for Colorado's low obesity rate is the extremely pure water that comes from snowmelt in the Rockies. They suggest that well water (which became more popular in the latter half of the 20th century) is a likely source of lithium contamination. And as I'd written above, New York City's water also come from a (probably) relatively pure source. In fact, the well water connection could possibly explain some of the low obesity in cities — no one in cities is using well water (I think! Right?).

So I took a look at where other cities get their water. San Francisco also gets their water mostly from a pure (I assume) source in the Sierra Nevada mountains, and has a very low obesity rate, around 15% in 2015.

Boston had an obesity rate of 22% in 2013-2015, according to this report. Suffolk County (home of Boston) had an obesity rate of 21% in 2017, according to this county-level map. Metro Boston gets its water from reservoirs in central/western MA. I don't see any obvious reason why these reservoirs would be especially pure. Massachusetts doesn't have large disparities in obesity — the most obese county is 31% obese, and the least obese is 21% obese. Compare that to New York, where according to the map above, Manhattan is 19.9% obese while there are multiple upstate counties over 40% obese.

San Diego County had a 2017 obesity rate of 20%, and gets its water from sources that don't seem especially pure, according to the snowmelt theory — it takes some of its water from the Colorado River, after it has traveled hundreds of miles. Multnomah County, home of Portland, Oregon, has an obesity rate of 24%, and gets its water from only 30 miles outside the city. The entire watershed is only "102 square miles", so it seems like the water doesn't have to travel very far to get from rainfall to being in the reservoir, so perhaps its relatively pure even though it doesn't come from snowmelt.

Overall, there's some interesting ideas to think about here, but I'm unable to convince myself that pure snowmelt water is a big deal — Denver's obesity rate is 17%, while Boston's is 21% and San Diego's is 20% with neither having water sources that appear at first glance to be especially pure. The trend does seem to be in the right direction — the cities that seem to have the cleanest water (Denver, NYC, San Fran) all have slightly lower obesity rates than the cities that have nothing-special water (Boston, San Diego, Portland). It seems more in line with contamination being one part of the obesity epidemic, not the only cause.

L. Other weird environmental effects

A few other "weird" (compared to the "conventional wisdom" that obesity relates mostly to diet and exercise) causes of obesity due to environmental effects have been suggested. The first one I found when I was reading the paper mentioned above on how elevated environmental CO2 levels leads to less nutritious plants. It's been suggested that elevated CO2 levels directly affect the human body in a way that causes obesity. The abstract of this paper is pretty impressive:

Coinciding with the increase in obesity, atmospheric CO2 concentration has increased more than 40%. Furthermore, in modern societies, we spend more time indoors, where CO2 often reaches even higher concentrations. Increased CO2 concentration in inhaled air decreases the pH of blood, which in turn spills over to cerebrospinal fluids. Nerve cells in the hypothalamus that regulate appetite and wakefulness have been shown to be extremely sensitive to pH, doubling their activity if pH decreases by 0.1 units. We hypothesize that an increased acidic load from atmospheric CO2 may potentially lead to increased appetite and energy intake, and decreased energy expenditure, and thereby contribute to the current obesity epidemic. [emphasis mine]

This is another example of a possible environmental contaminant, so it is not a rebuttal to SMTM's hypothesis as much as it is another possible contaminant separate from any that they've pointed to. The CO2 hypothesis would also help explain SMTM's "mystery" of lower obesity for people living at higher altitude. There's some evidence CO2 concentrations are a bit lower at higher altitudes. (The lack of oxygen at higher altitudes also does weird things to our blood, which needs to compensate in order to continue delivering the right amount of oxygen to the body, so this could disrupt the CO2— pH of blood — obesity process as well. See, for example, The Sports Gene by David Epstein.)

Another commenter links a paper that reports a link between being exposed to artificial light and obesity. The idea, roughly, is that a disrupted circadian rhythm messes with our metabolic system in a way that makes us more obese. One of their arguments is that there's a correlation between countries with high amounts of artificial light and high rates of obesity:

But it's hard to say if this correlation just happens because of all the other things that correlate with artificial light (modern lifestyles and diets, modern environmental contaminants). However, I think the next argument in the paper is a bit more convincing: there's solid evidence that a disrupted circadian rhythm is not only correlated with obesity, but actually induces obesity:

...human shift work was associated with weight gain, increased BMI and associated co-morbidities such as metabolic syndrome and type-2 diabetes, that were independent of life-style and work related factors. This finding has been reported consistently in shiftworkers from all over the world, and from various working environments...A recent study examined 7254 shiftworkers over 14 years and concluded that shiftwork was a significant risk factor for obesity that was independent of age, BMI, drinking, smoking or exercise...Furthermore, experimental circadian desynchrony disrupted glucose homeostasis in human volunteers, with several previously healthy individuals showing postprandial glucose and insulin levels that were in the range of the pre-diabetic state...

The authors of this paper also bring up the issue of animals getting fatter, suggesting that this could be explained by light pollution, since animals are subject to it just as much as we are. But I'm not sure how this hypothesis could explain the extremely low obesity rates in walkable cities — I would've expected cities to be the areas with the most circadian-disrupting light pollution.

Another commenter suggests the idea that getting UV exposure (being outdoors) could be linked to obesity, as well. There are some weird links between UV exposure and obesity in mice and a malaria drug that makes you sunburn more easily also helping glycemic control. These results are somewhat hard to separate from both the CO2—blood pH hypothesis (there's both more UV exposure and less CO2 at higher altitudes) and from the artificial light hypothesis.

Eventually, I clicked my way into a series of papers that do more or less what I'm doing here: summarize some of the "weirder" explanations for the obesity epidemic. Here are a few more that I've found through those sources:

1. Increased use of heating and AC. "Cold environments stimulate energy expenditure via activation of brown adipose tissue...It is a common observation that excessive heat and humidity inhibit appetite...". And we don't necessarily just eat more to offset the energy we spend warming up:

Studies of changes in food intake, which have the potential to compensate for reduced energy expenditure at temperatures of thermal comfort, suggest that while some intake adjustment to restore energy balance takes place, this is unlikely to compensate fully for reduced expenditure

Cold exposure increases the amount of that brown adipose tissue (BAT) in the body:

Unlike white adipose tissue which acts predominantly as an energy storage depot, BAT [dissipates] energy in the form of heat...until recently the functional role of BAT in adult humans was believed to be negligible. However, recent research has demonstrated that BAT has a more significant role in adult thermogenesis than was previously thought...

...the potential energy expenditure of the BAT seen in this study could, if fully activated, contribute substantially to energy balance, expending energy equivalent to 4 kg of adipose tissue over the course of a year...

[An] association between chronic cold exposure and BAT has been observed in humans: with larger BAT deposits and greater aerobic energy metabolism in the adipose tissue of Finnish outdoor workers compared with indoor workers.

2. Increasing age of mothers at birth:

Wilkinson et al. studied obese British children and found that a common risk factor was having an elderly mother. Patterson et al. studied girls aged 9–10 years and found that the odds of obesity increased 14.4% for every 5-year increment in maternal age...Symonds et al. observed a correlation between maternal age and fat deposition in sheep...

Mean age at first birth has increased by 2.6 years among US mothers since 1970...[this increase] in maternal age might produce a clinically meaningful 7% increase in the odds of obesity.

That Patterson is a pretty old study, so there's a good chance that it's a case of "correlation but no causation", but they do control for "household income, maximum parental education, employment status, number of parents/guardians in household...". This doesn't seem to have been followed up on very much — I couldn't really find any newer studies that explored and built off these results.

M. Some Closing Thoughts

Here are a few quick ideas, some mentioned above already, that I want to stress:

Science is hard. Lots of the studies cited by SMTM have imperfect methodology, and lots of the studies that I cite do, too. There's so much data we wish we had and experiments we wish had been run.

Gaining weight and losing weight are not necessarily symmetrical. Just because a good diet won't make it easy to lose 20 pounds doesn't mean that a bad diet didn't, in some sense, "cause" that weight gain. The amount of working out needed to lose 20 pounds isn't necessarily the same as the amount needed to not gain 20 pounds.

It's incredibly hard to lose weight. Even if I think I have a solid idea on what's caused our obesity epidemic doesn't mean that I think losing weight is easy. Pretty much every study ever done has shown that it's incredibly hard to lose weight (except maybe this one).

The lipostat is in the brain, and the brain is incredibly complicated. I think assuming we know exactly what can or can't affect the lipostat is a fool's errand — the lipostat is in the brain, and almost anything the brain does could influence other processes in the brain. That's why trauma and social networks can (probably) influence our weight. Here's another example, from the book Exercised, of how our habits can change our brain chemistry, no contaminants needed:

...dopamine receptors in the brain are less active in people who haven’t been exercising than in fit people who are regularly active. And to add insult to injury, people who are obese have fewer active dopamine receptors. Consequently, non-exercisers and obese individuals must struggle harder and for longer (sometimes months) to get their receptors normally active...

If one aspect of lipostat is "how your brain responds to exercise", then non-exercisers experience a negative feedback loop, while habitual exercisers are on a positive feedback loop. Brain patterns can be affected by things other than chemical contaminants!

Correlation is not Causation. There are so many things that correlate with obesity, but probably most of them don't cause obesity. SMTM has brought this up before (do people eat more because they've gained weight, or gain weight because they ate more?), so I've tried to reply by, where possible, citing studies that show things that predict obesity. But, even if something predicts obesity, it doesn't even necessarily mean that it caused obesity — perhaps environmental contamination caused someone's brain to change in a way that led to more emotional eating. Emotional eating predicted obesity, but it was still "caused" by the contamination (in this hypothetical).

Writing this essay, I'm consistently reminded of the famous "What if we create a better world for nothing?" cartoon:

Perhaps I'm wrong about 9 out of 10 of these suggested causes of obesity. Maybe we get CO2, lithium, light pollution, vegetable oils, livestock antibiotics, and ultra-processed foods out of our environment and create a world with more activity, more healthy eating, less trauma, and better sleep habits. Maybe we do all that and still don't solve the obesity crisis. But it would still be worth it! Yes, there are always trade-offs, but overall I'm just an optimist that we can do these things and create a better world.

Conclusion: So what is causing the obesity epidemic?

SMTM says the environmental contaminants are "the only cause of the obesity epidemic". I don't agree that contaminants are the only cause, but SMTM has convinced me that they are one cause. I'm going to throw out some made-up numbers as to what I think are the causes of the obesity epidemic. These are completely made up, but hopefully they still have some use:

Less Americans smoking: 10%

Americans are less active & less muscular: 20%

Food is tastier, more available, and less nutritious: 25%

Better at keeping obese people alive: 5%

Environmental contaminants: 20%

Circadian disruption: 5%

Increasing stress levels: 5%

Network effects/"social communicability": 5%

Things not mentioned above that we still don't know about: 5%

Finally, I want to note that there are different "levels" of talking about what "causes" obesity. I've chosen not to make this post about the system-level factors that lead to the causes I've offered for the obesity epidemic. For example, when I say "Americans are less active", I'm not trying to say "people are lazy and lack willpower". There might be a bit of that, but there are also systemic reasons (suburbs making walking places impossible, etc) why people haven't been active enough.

=================

2022-05-13. Edited to add:

There are a few things that have caught my eye in the months since I wrote this.

First:

A comment on Data Secrets Lox points out that lead is an appetite suppressant. Wikipedia agrees:

Early symptoms of lead poisoning in adults are commonly nonspecific and include depression, loss of appetite...

Gastrointestinal problems, such as constipation, diarrhea, poor appetite, or weight loss, are common in acute poisoning...

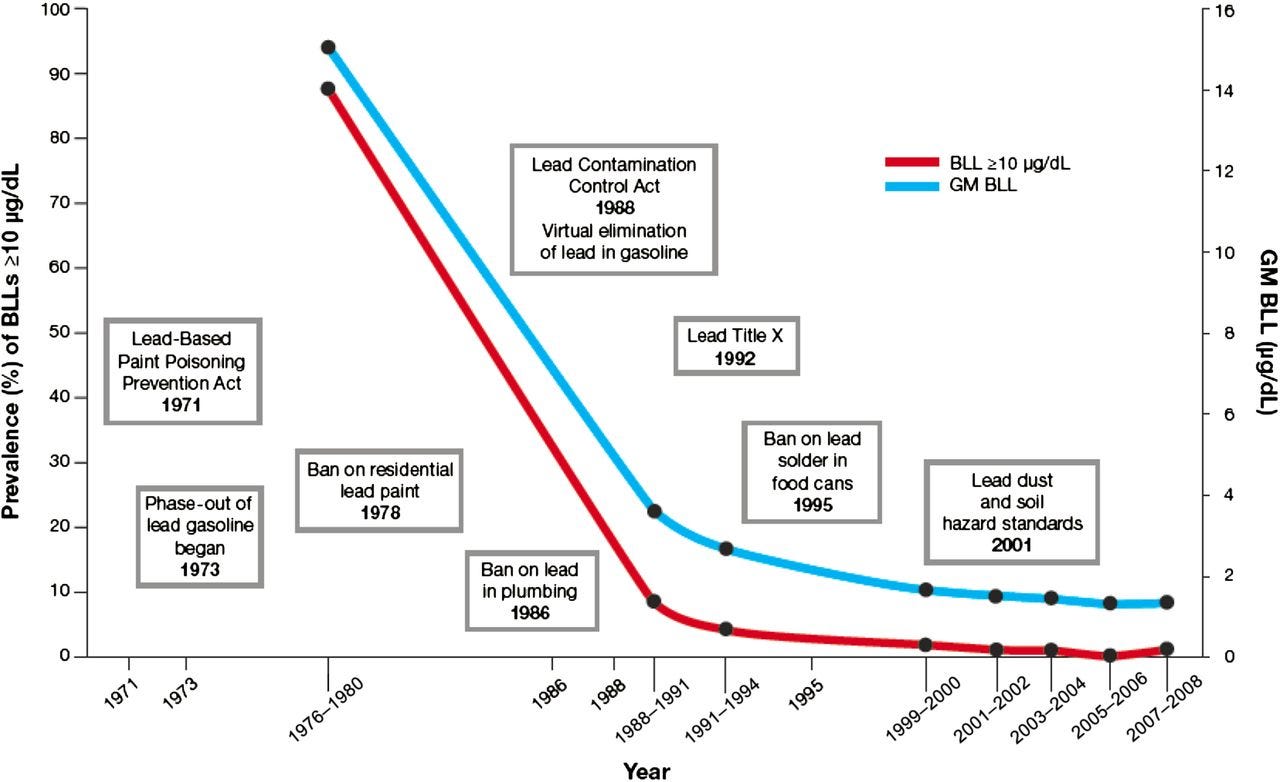

And as we know, lead levels have decreased drastically since we realized how bad lead poisoning is in the 1970s:

So, there's a clear & simple argument that lead, like nicotine, is an environmental contaminant that has caused increased obesity (compared to 50 years ago) due to our success in getting it out of our environment. From the few minutes I spent looking up this information, it seems like this aspect is understudied, especially compared to nicotine. But I could see this being an explanation for ~5% of our obesity epidemic. Now, I admit that I have no idea what "10 micrograms per deciliter" means in practice, and whether that's a high enough dose to cause loss of appetite/weight loss. But, we know these two things very clearly: 1. lead poisoning causes loss of appetite and weight loss and 2. There used to be way more lead in the environment than there is now.

Second:

I recently read Ingredients by George Zaidan, which covers a study I mentioned above:

A Reddit comment also pointed me to this study showing that people gained more weight on an "ultra-processed" diet, and the reason was that they chose to eat more.

Zaidan comes up with a number of reasons why this study might not be as impressive as it seems. However, his focus is on whether the act of "processing" itself is bad. So some of his criticisms (e.g, paraphrasing, 'the ultra-processed diet was tastier — people just like tastier food', or 'the ultra-processed diet was more energy dense, which people like more') counter the idea that "processed food is bad", but don't counter my point — that we eat more food than we used to because it's tastier than it used to be. Here's his conclusion:

So, does this trial change how I see the evidence against ultra-processed foods?

Yes, a little.

This trial shows that ultra-processed food caused a group of overweight young people to put on weight. But—stick with me here—we cannot conclude that processing was the reason that ultra-processed foods caused the weight gain.

At first glance, this makes zero sense. How can we know that ultra-processed foods did something, but not know whether they did it because they were processed? It comes down to the fact that ultra-processed foods are a whole bunch of variables tied together in one convenient package: energy density (high), volume (low), flavor (delicious), location of production (factory), salt level (high), and so on. Because some of these variables remained stubbornly unmatched in Hall’s study, it’s impossible to tell which of them was responsible for the weight gain. Was it the processing? Maybe. But maybe not. It could have been the energy density. Or the type of fiber. Or the taste. And so on.

You can think of it like the distinction between knowing that ultra-processed food causes weight gain vs. knowing why it does. We always want to know why, but sometimes you have to start with the that. Hall’s study is a necessary and important first step down the path. More experiments will follow.

Third:

The blog Resident Contrarian has a new post, similar to mine, criticizing Slime Mold Time Mold's environmental contamination theory. He says his post is the first of a few. He's started on a similar path that I took in my post above — focusing not on evidence that the contamination theory is false, but on areas where SMTM hasn't provided the strongest version of the evidence that other, traditional explanations of obesity are true. One thing that caught my eye is a comment left by commenter Joseph Montanaro, saying:

Scott Alexander did a review of "The Hungry Brain" a while back; I assume you've read it since I know you've read most of his stuff but it does reference what I think is one such study:

"In 1965, some scientists locked people in a room where they could only eat nutrient sludge dispensed from a machine. Even though the volunteers had no idea how many calories the nutrient sludge was, they ate exactly enough to maintain their normal weight, proving the existence of a “sixth sense” for food caloric content. Next, they locked morbidly obese people in the same room. They ended up eating only tiny amounts of the nutrient sludge, one or two hundred calories a day, without feeling any hunger. This proved that their bodies “wanted” to lose the excess weight and preferred to simply live off stored fat once removed from the overly-rewarding food environment. After six months on the sludge, a man who weighed 400 lbs at the start of the experiment was down to 200, without consciously trying to reduce his weight."

Resident Contrarian replies to the comment, pointing out:

So I agree on most of this, but I would point out that SMTM's theory mostly has to do with the post 1980's period of time...I'd love to see them re-run the same experiment now...

In a similar vein, SMTM's new "Potato Diet Community Trial" will help test this theory. It's not quite "nutrient sludge", but it is a pretty boring diet. They quote the "Potato Hack" website saying:

To get the full benefit of the potato hack, it is strongly advised to eat the potatoes plain. You are teaching your brain how to get full without flavor. This is the opposite approach taken in dieting where one continues to get flavorful food but in a restrictive manner.

One of the commenters puts it this way:

The Potato Hack works on 2 levels. First by “volumetrics”. Filling the stomach with a low-calorie food that shuts down hunger better than any other food. The second level is by resetting the brain’s connection between hunger, flavor, and calories. You teach your brain that high flavor foods are no longer required to fill full. It is the opposite of what the processed food industry does.

I'll be curious to see their results.

Fourth:

In The Upside of Stress, I read about this study called "Mind over Milkshakes". I'll quote the summary provided in the book:

The “Shake Tasting Study” invited hungry participants to come to the laboratory at eight in the morning after an overnight fast. On their first visit, participants were given a milkshake labeled “Indulgence: Decadence You Deserve,” with a nutritional label showing 620 calories and 30 grams of fat. On their second visit, one week later, they drank a milkshake labeled “Sensi-Shake: Guilt-Free Satisfaction,” with 140 calories and zero grams of fat.

As the participants drank the milkshakes, they were hooked up to an intravenous catheter that drew blood samples. Crum was measuring changes in blood levels of ghrelin, also known as the hunger hormone. When blood levels of ghrelin go down, you feel full; when blood levels go up, you start looking for a snack. When you eat something high in calories or fat, ghrelin levels drop dramatically. Less-filling foods have less impact.

One would expect a decadent milkshake and a healthful one to have a very different effect on ghrelin levels—and they did. Drinking the Sensi-Shake led to a small decline in ghrelin, while consuming the Indulgence shake produced a much bigger drop.

But here’s the thing: The milkshake labels were a sham. Both times, participants had been given the same 380-calorie milkshake. There should have been no difference in how the participants’ digestive tracts responded. And yet, when they believed that the shake was an indulgent treat, their ghrelin levels dropped three times as much as when they thought it was a diet drink. Once again, the effect people expected—fullness—was the outcome they got. Crum’s study showed that expectations could alter something as concrete as how much of a hormone the cells of your gastrointestinal tract secrete.

What does this study say about our understanding of obesity? I'm not exactly sure! I just thought it was really interesting. But here's a few stray thoughts:

It's yet one more piece of evidence showing the connection between hunger and the brain.

We feel more satiated after a meal that we believe was filling, regardless of how filling it actually was. So if this were to play into the obesity story, it would be because we think meals are not filling when they actually are, causing us to continue to feel hungry & eat more. I'm not sure this fits too strongly with any "standard explanation" of obesity — though perhaps it relates to what I mentioned above about energy-dense foods and the potato diet: our brain thinks that small things are not as filling, even if they're incredibly energy dense. Another aspect is that it may help explain why dieting "doesn't work": on a diet, we expect to eat meals that aren't filling, and then that expectation becomes reality.

I'm not sure this study has caused me to change any of my views about obesity, but it's definitely an interesting piece of science.

I suspect that low urban obesity is largely driven by class confounders: very high concentration of SWPLs/Brahmins rather than proles/Vaisyas. Same with Northern Virginia. SWPLs tend to actively care about their health and pride themselves on eating whole foods rather than processed foods, so it's not surprising that they're thinner (probably also somewhat lower genetic load).

Likewise, I don't think most diet/exercise based explanations can explain why obesity has shot up so much more quickly in the past ~20 years. I can maybe buy less hyperpalatable food and more exercise in 1970 then today, but I highly doubt there's been a major shift in the past couple of decades. More food also doesn't jibe with stuff like the China study data from Nanan, where sedentary office workers were consuming ~3600 kcals a day at a baseline weight of 120 pounds (far more kcals/pound then modern Americans), and not getting fat (https://fireinabottle.net/the-curious-case-of-nanan-and-huain/). The one exception is the linoleic acid/seed oil hypothesis, because vegetable consumption has risen monotonically basically everywhere over the past ~20 years. If had to put money on one major driver of obesity, it would be that (don't find Slime Mold's criticisms convincing for a number of reasons), but still low confidence that that's correct.

Protein/nutrient leverage may have something to do with it, but I think that "paleo" diets and related ones (high on meats, eggs, vegetables, and other very nutrient dense foods) would be more successful if that was a major factor. These diets do work pretty well, but not so well that they're a magic bullet, which they should be if protein/nutrient leverage is the major driver of obesity. And then you have things like the rice diet, potato diet, and croissant diet, all of which also work fairly well, when they should be utter garbage if protein/nutrient leverage is a major driver.

As for muscle strength: the obvious question then becomes, "why are we weaker"? Were Americans in 1990 really doing backbreaking labor compared to Americans in 2020? It probably has something to do with the massive generational decline in male testosterone... but nobody knows what's causing that. And as far as I know, T levels have been increasing outside the West, yet India and China are now getting full-force diabesity as well.

Increasing maternal age is an interesting point, one which I hadn't seen yet. Maybe feminism is what's causing the obesity crisis. Lower T in men (thus weaker and fatter), higher T in women (associated with more visceral fat in women), fat acceptance (for those social network effects), fewer homecooked meals, higher maternal age... (but I don't think this is actually true: the Middle East is the world's fattest major region, and certainly not the most feminist, especially not in 1970).