“I always advise my people to read outside your field, everyday something. And most people say, ‘Well, I don’t have time to read outside my field.’ I say, ‘No, you do have time, it’s far more important.’ Your world becomes a bigger world, and maybe there’s a moment in which you make connections.”

Range is written by David Epstein. The subtitle is "Why Generalists Triumph in a Specialized World". According to my book tracking spreadsheet, I finished reading Range in June 2021(!). I started a book review, got distracted by other writing projects that I was more excited about, and then never got back to it.

A friend recently told me they were reading Range, which sparked my interest in going back and finishing my review. Skimming through the book again, I'd forgotten how it touches on just about everything I'm interested in: skill development (How to practice throwing), effective learning techniques (An introduction to the science of learning, for frisbee throwers), knowledge transfer across domains (Get better at frisbee without leaving your room, see section on brain games), the way our brains use analogy (Book Review: The Language of Coaching)...The list goes on—literally, here are a few more examples:

Epstein says "An enthusiastic, even childish, playful streak is a recurring theme in research on creative thinkers"—something I talked a tiny bit about in my review of Playful Parenting. I think playfulness works for both creativity and for effective coaching (and perhaps social interaction in general). My blog is generally pretty serious but I'm goofy in real life. At practice earlier this week, I happened to ask one of my players: "are we seriously silly, or sillily serious?" (She chose the first option; I chose the second). We need to find the right balance between serious and silly—as we do between range and depth, but more on that later.

Another way Range fits my preconceived notions: Epstein writes in favor of seemingly "risky" career changes, saying:

Forty-five of the first fifty subjects [recruited for a study of successful professionals] detailed professional paths so sinuous that they expressed embarrassment over jumping from thing to thing over their careers. “They’d add a disclaimer, ‘Well, most people don’t do it this way,’” Ogas [the researcher conducting the study] said. “They had been told that getting off their initial path was so risky. But actually we should all understand, this is not weird, it’s the norm.”...

Obviously, there’s nothing wrong with getting a law or medical degree or PhD. But it’s actually riskier to make that commitment before you know how it fits you. And don’t consider the path fixed. People realize things about themselves halfway through medical school.

I quit my job to blog about frisbee and study Chinese, so it's definitely reaffirming to see someone write in favor of odd career changes. I've always read a lot of books, and the quote I included at the beginning of the review is something I've been wanting to tell friends for many years. He writes that "scientists who have worked abroad—whether or not they returned—are more likely to make a greater scientific impact than those who have not", and I worked abroad for a couple years.

All that is to say, Range fits a lot of my preconceived notions about the world. If you find yourself wanting to disagree with the themes of the book, I'm happy to admit that I'm probably a bit biased.

So, what is Range?

Don't consider my review to be a summary of the book. I focus on the parts I find interesting instead of recapping every chapter. But as a general summary, Epstein says that it's more beneficial to have a range of skills than to be hyper-specialized. Here's some of the research he uses to justify his thesis:

Forecasters who have "one big idea" of how the world works make worse predictions

People can become too attached to their ways of thinking. Firefighters have died because they were unwilling to drop their tools.

Athletes who specialize too early are less likely to become elite

Economists have shown that switching jobs allows people to find a better match for their skills. People worry about being "behind" but they're likely to have found a better fit than someone who decided on a career earlier.

Comic book writers who have experience in a higher number of genres are more likely to write a hit.

"Interleaving" practice produces better results than "blocked" practice (sort of a micro- version of range)

Innovators often draw on analogies from other fields or other life experiences to solve problems.

Researchers who write papers that cite sources from more varied fields are more likely to write "blockbuster" papers.

As you can see, the book itself it pretty wide-ranging: sports, career choice, creativity and innovation.

He argues that one benefit of range is allowing us to benefit from analogical thinking. Being able to say "this problem is like that problem" is a powerful problem-solving tool:

Analogical thinking takes the new and makes it familiar, or takes the familiar and puts it in a new light, and allows humans to reason through problems they have never seen in unfamiliar contexts...Our natural inclination to take the inside view can be defeated by following analogies to the “outside view.”

In other words, exploring more fields allows us to collect more mental models.

Range vs. depth

Epstein writes in favor of range, but there's a hidden assumption that you need depth, too. I've written about this before, in my review of How We Learn To Move:

At times [author Rob Gray] seems to be suggesting that we should never "practice", and only "play". But he also spends a lot of time telling us that some of the newer practice methods that he helped invent are very effective. So he clearly understands that to be great, you need to practice a whole lot. But I worry that message gets lost in his anti-repetition crusade…

He's not arguing that you don't have to practice a lot (assuming that "practice" is done the right way). He's arguing against a very specific definition of the terms "repetition" and "automatic". His own path still involves a lot of hard work, and it still involves experts having a high level of repeatability in their outcomes.

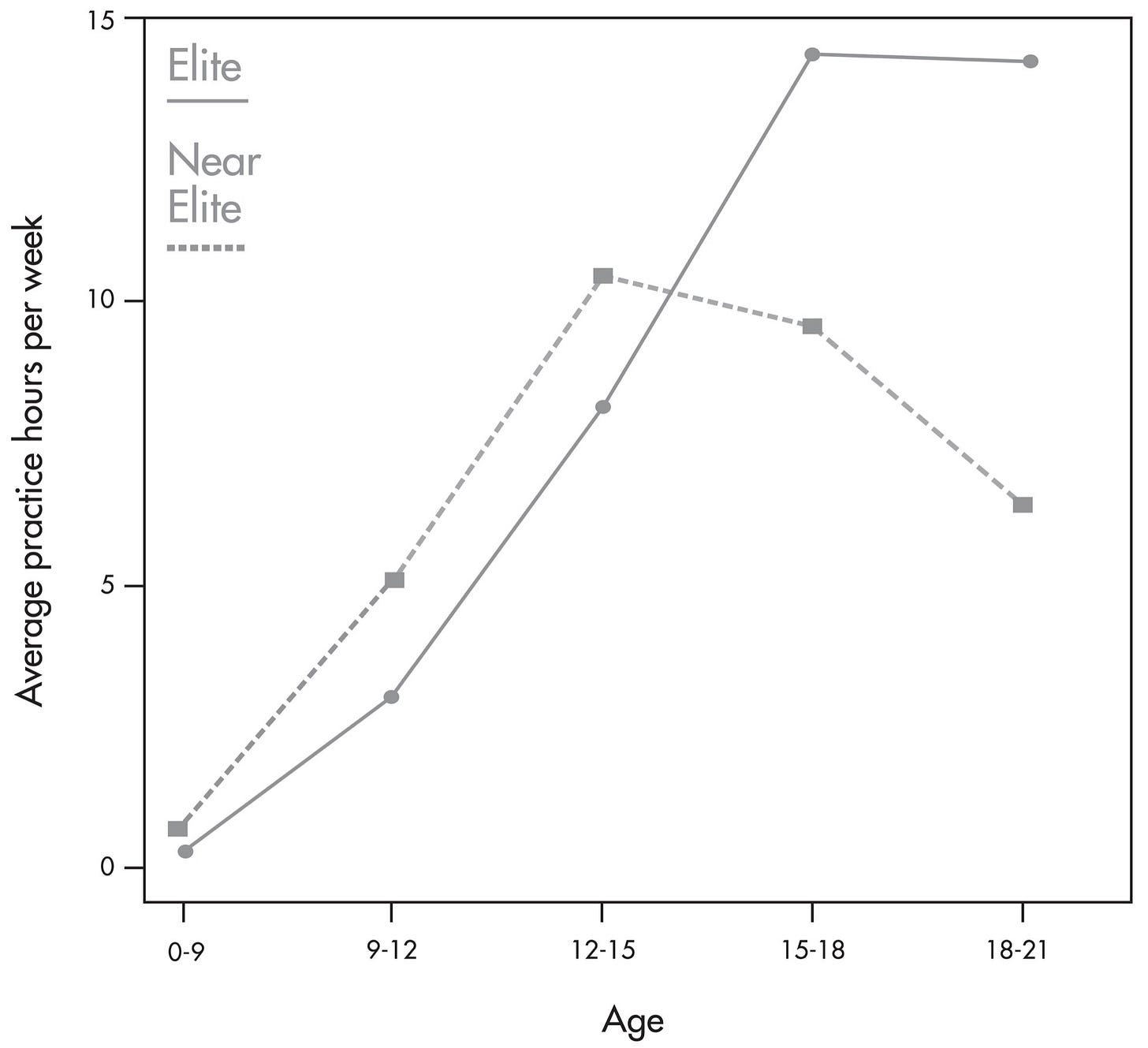

Epstein does the same thing in Range, to an extent. One innovative researcher he profiles is Oliver Smithies. Smithies is someone who exemplifies the ideals of range—but he's also someone who has two bachelor's degrees and a PhD. There's depth there, too. Early in the book, Epstein argues against early specialization in sports, pointing out that many elite athletes don't specialize until relatively late (as mentioned in the bulleted list above). He includes this graph from a study of elite and near-elite athletes:

Yes, the 12-year-olds who turn out to be elite athletes are practicing less than their peers at that age. But practicing two hours a day from age 15 to 18 is an important part of their success, as well.

My experience growing up playing sports has helped me as a frisbee player. But equally important is all the time I've spent playing frisbee after I found it. Range without depth is just jumping between hobbies.

Kind and wicked

Epstein divides fields into "kind" learning environments (clear patterns and clear feedback, like chess or golf) and "wicked" learning environments (complicated systems with less immediate feedback—common in our big, complex world). He thinks sports like soccer (or ultimate frisbee) are more wicked, writing:

The “free play” of intellects sounds horribly inefficient, just like the free play of developing soccer players who could always instead be drilling specific skills. It’s just that when someone actually takes the time to study how breakthroughs occur, or how the players who grew up to fill Germany’s 2014 World Cup winning team developed, “these players performed less organized practice...but greater proportions of playing activities.”

There are certainly some wicked aspects to sports like ultimate frisbee, but his explanation of how golf is a kind environment could apply to throwing frisbees by just changing a few words:

Drive a golf ball, and it either goes too far or not far enough; it slices, hooks, or flies straight. The player observes what happened, attempts to correct the error, tries again, and repeats for years. That is the very definition of deliberate practice, the type identified with both the ten-thousand-hours rule and the rush to early specialization in technical training. The learning environment is kind because a learner improves simply by engaging in the activity and trying to do better.

Soccer and frisbee have a mix of kind and wicked elements. You can get better at throwing using the practice-and-feedback loop, but you won't become an elite player—an elite decision-maker in a chaotic environment—without playing lots and lots of frisbee.

I tend to think that most situations are a mix of kind and wicked, and thus reward a mix of range and depth. You can't win a Nobel Prize without some spark of range-inspired creativity...but you also probably won't win a Nobel without lots of hard work to master the current knowledge in your field.

The science of learning and the limits of mixing

I've read about (and written about) 'mixed' practice being more effective than 'blocked' practice. Reading Range is where I learned that not only is "blocked" practice a worse way to go, but that learners think they're learning more when they're actually learning less effectively:

80 percent of students were sure they had learned better with blocked than mixed practice, whereas 80 percent performed in a manner that proved the opposite.

One thing I'd really like to understand better, though, is: what is the right amount of "interleaving" (mixing different types of practice together)? The books I've read focus on our tendency to not include enough variation. But some amount of repetition is necessary too. To bring out what I mean by that, let me use a couple examples from my interests:

1. I'm interested in learning languages. What's the right amount of interleaving when learning languages? Does mixing mean studying all of my Chinese flash cards at once, without over-specializing by focusing on one vocabulary "theme" at a time (household words, science-related words, etc)? Or should I mix even more than that, and mix my study of Chinese words with words from other languages?

2. There are many, many different ways to throw a frisbee (especially for me—I'm ambidextrous). There are forehands and backhands and throws with an arm motion like a football throw. "Backhands" can be broken down into throws that curve left-to-right, or right-to-left; long throws, short throws; throws where I release the frisbee near the ground or way up in the air above my head; etc etc. So what's the right amount of interleaving? Do I practice a bunch of different types of right-handed backhands in a session? Or do I also mix in all my other throws in every practice session? Or is even "right-handed backhands" too broad a category, with too much possible variation for the most efficient learning?

I can't help but feel a connection between balancing repetition and variation in practicing with the concept of entropy in information theory. The equation of entropy in information theory says (in a non-mathematical example): you can't communicate with someone if there's not enough uncertainty about what's going to happen (if your overly-polite dinner guest would tell you they enjoyed dinner whether they actually liked it or not, you don't learn anything when you ask them if they liked dinner and they say "yes"), but you also can't communicate with someone if there's too much uncertainty (you also won't find out if they liked dinner if you asked them what they thought and they reply, "g=190[ihgo;nb").

Learning through interleaving seems similar: you shouldn't literally practice the exact same thing over and over again, but you also shouldn't literally never practice the same thing twice. There's a sweet spot where you get enough repetition to learn but enough variation to keep the challenges fresh. I took the diagram from the "entropy" article on Wikipedia and updated it for learning:

This analogy of balance has come up a few times in this review:

Range works best (for life success) when we combine it with depth

Variation works best (for effective learning) when we get enough repetition to learn from feedback

Silliness works best (for creativity) when we combine it with a healthy dose of serious study

I like the way these ideas connect together. Perhaps it's just another way of saying "everything in moderation, including moderation". Or as I mentioned above, range and depth are like large-scale versions of variation and repetition.

Final thoughts

Recently I was having a chat with one of my players about the concept of "work smarter, not harder". To me, the benefits of chasing range are a way to work smarter. If you have the exact same skills as your colleagues (at work) or opponents (on the field), the only way to be above average is to work harder than they do. But with different types of knowledge, we can find new ways to solve problems.

The one thing I hope a few people take away from this review is the quote I included at the top: whether it's reading a book outside of your field of study or playing a sport other than the one you focus on, you shouldn't be thinking "I don't have time to"—in truth, you don't have time not to.