[Note: This essay is long and different from my usual posts about frisbee. Don't feel bad about skimming or skipping it. But maybe a little unexpected weirdness is exactly what you need today. Enjoy!]

When Vacchagotta the wanderer asked him point-blank whether or not there is a self, the Buddha remained silent, which means that the question has no helpful answer. As he later explained to Ananda, to respond either yes or no to this question would be to side with opposite extremes of wrong view. Some have argued that the Buddha didn’t answer with “no” because Vacchagotta wouldn’t have understood the answer. But there’s another passage where the Buddha advises all the monks to avoid getting involved in questions such as “What am I?” “Do I exist?” “Do I not exist?” because they lead to answers like “I have a self” and “I have no self,” both of which are a “thicket of views, a writhing of views, a contortion of views” that get in the way of awakening. (Source)

When I first heard there’s an idea in Buddhism that there is no self, it sounded like a woo-woo belief. Wikipedia says 'no self' is the idea “that there is no unchanging, permanent self, soul, or essence”. In his book Why Buddhism is True, Robert Wright adds more detail about what the Buddha argued:

The logical place to begin is with the primordial text, Discourse on the Not-Self, which is said to be the Buddha’s earliest utterance on the subject...

The Buddha’s strategy in this discourse is to shake the monks’ confidence in their traditional ideas about the self by asking them where exactly, in a human being, we would find anything that warrants the label self. He conducts this search systematically; he goes through what are known as the five “aggregates” that, according to Buddhist philosophy, constitute a human being and that human’s experience. Describing these aggregates precisely would take a chapter in itself, but for present purposes we can label them roughly as:

(1) the physical body (called “form” in this discourse), including such sense organs as eyes and ears;

(2) basic feelings;

(3) perceptions (of, say, identifiable sights or sounds);

(4) “mental formations” (a big category that includes complex emotions, thoughts, inclinations, habits, decisions); and

(5) “consciousness,” or awareness—notably, awareness of the contents of the other four aggregates.

The Buddha runs down this list and asks which, if any, of these five aggregates seem to qualify as self. In other words, which of the aggregates evince the qualities you’d expect self to possess?

It's not worth going into the details of the Buddha's argument here, but you won't be surprised to hear he convinces the monks that there is no self. (Side note: "not-self", used in the first paragraph of the above quote, is perhaps the more technically correct term. I use "no self" in this essay because it’s more familiar to me.)

As the quote at the beginning of this article suggests, there's a lot of nuance to the question of whether Buddhism truly argues there is no self. But at the very least, 'no self' is a core part of how the Western world understands Buddhism. If you've been on the internet long enough, you're sure to have come across this joke:

What did the Buddha say to the hot dog vendor?

"Make me one with everything!"

On the surface, no self sounds crazy, right? It sure seems like there's a such thing as the 'self'—I'm me and you're you. We're not all one entity. I originally thought so too, but the more I’ve read about science, the universe, the brain, and the body, the more examples I saw that no self is arguably our reality.

I’m not an enlightened Buddhist. I walk around every day feeling like I’m me—like I have a self—just like (most of) the rest of y’all. So when I say no self is true, I mean that it's something I believe logically, but not something I consistently feel.

Below is a list I've compiled of the many ways 'no self' is scientific truth. Think of it as the arguments the Buddha might make if he were a 21st century scientist. Some of these examples are a bit of a stretch, but I include them all in hopes that many little pieces of evidence grow more convincing when they're all considered together.

Biology

1. The Ship of Theseus — our cells are constantly dying

There’s a famous thought experiment called the Ship of Theseus paradox. Here's Wikipedia's explanation:

The ship wherein Theseus and the youth of Athens returned from Crete had thirty oars, and was preserved by the Athenians down even to the time of Demetrius Phalereus, for they took away the old planks as they decayed, putting in new and stronger timber in their places, insomuch that this ship became a standing example among the philosophers, for the logical question of things that grow; one side holding that the ship remained the same, and the other contending that it was not the same.

The human body is subject to the same paradox: our cells die, and are replaced throughout our lives. Some of the atoms from the pasta you ate last week and from the breath you took an hour ago are now part of you. So: is the "self" you were 10 years ago the same person as the "self" you are now, when that self is made up of different cells?

According to the link above, some brain cells seem to live as long as we live. But at least some brain cells do die, especially as we get older (source). Would that imply an older person is less of a "self" than a younger person?

(There are lots of other examples here too—do your hair and nails remain part of you until the exact moment you clip them? Is there some moment after eating a meal that the food you ate becomes part of you? Is there a specific moment the urine in your bladder is no longer part of your self? Your brain wiring is constantly changing as you learn and experience new things, so even that isn't a shared feature of both current you and past you.)

The human microbiome is the term for all of the microorganisms (for example, bacteria) that live in our body. And there are a lot of them. The Wikipedia article linked above says there are roughly as many microorganism cells in our body as there are cells that belong to “us”, if not more! Should I introduce myself by saying, “Hi I’m Luke and also 50 trillion microorganisms”? Is “me” Luke, or is “me” Luke and also 50 trillion microorganisms?

In the last few years, we’ve seen more evidence microorganisms are not just tiny things that happen to be inside us; they have real effects on our lives, our thoughts, and our moods. From a news item titled, “Gut Bacteria Can Influence Your Mood, Thoughts, and Brain”:

How can lowly gut bacteria down there affect higher functions up there in the brain? ... [One way is that] gut bacteria produce neurotransmitters that are important for behaviors, mood, thoughts and other cognitive abilities.

Also, some microbiota can change how these brain chemicals get metabolized in the body and thus determine how much is available for action in blood circulation. Other chemicals generated by gut bacteria are called neuroactive, such as butyrate, which has been shown to reduce anxiety and depression... The immune system is intimately connected to the gut microbiome and the nervous system, and thus can be a mediator of the gut’s effects on the brain and the brain’s effects on the gut.

Here's another paper showing a correlation between lower levels of loneliness and higher levels of diversity in a person's gut microbiome.

There's a lot we still don't know about the human microbiome. But there’s strong evidence that the way we think and feel depends on microorganisms that don’t share our DNA. So: how can there be one, independent 'self' when (a) we are filled with organisms that don't share our genetic code and (b) those organisms—which are clearly not-us—affect the way we think and feel?

3. Parasites change 'us', too

In the last section we saw our behavior is affected by the microorganisms naturally living inside us. The same is true of microorganisms that aren't supposed to be there—things we get infected with. It sounds like something out of The Last of Us—but it's real (although much more mundane).

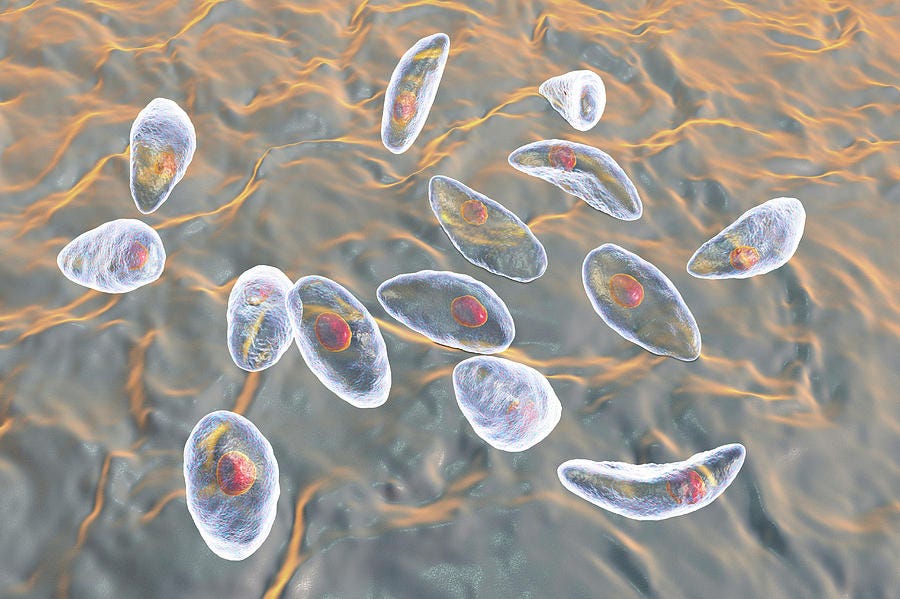

Research published in 2020 showed that infection with a parasite (Toxoplasma gondii) can cause people to be more likely to become an entrepreneur. From the abstract:

There is growing evidence that human biology and behavior are influenced by infectious microorganisms. One such microorganism is the protozoan Toxoplasma gondii (TG). Using longitudinal data covering the female population of Denmark, we extend research on the relationship between TG infection and entrepreneurial activity and outcomes. Results indicate that TG infection is associated with a subsequent increase in the probability of becoming an entrepreneur, and is linked to other outcomes including venture performance. [bolding added by me]

(PS — Here's another paper with similar findings.)

Parasites are able to "hijack selfhood" to an even greater degree in other animals. They can cause ants to climb to the top of a blade of grass so they'll be more likely to get eaten by cattle. The same Toxoplasma gondii mentioned above can cause mice to be attracted to the scent of cats. While we haven't seen the same level of hijacking in humans infected by parasites, these examples are a reminder that parasites have a real ability to affect much larger organisms.

One of the ways I think of my self is that I am the way I think and behave. But it turns out a parasite can cause me to behave differently—in subtle ways that have nothing to do with what I might expect a parasite to do, i.e. make me sick. And if that's the case, then how can my self be the way I behave? If that was true, getting infected with a parasite would make me a new person.

4. The Selfish Gene Hypothesis

The selfish gene hypothesis, also known as the “Gene-centered view of evolution”, says that the process of evolution that resulted in us humans is not survival of the fittest organisms, but survival of the fittest genes.

In this view, our bodies (including our brains) are nothing but “survival machines” for the immortal genes that 'want' to be reproduced into the next generation.

The genes that have survived to today are the ones that do the best job of convincing their machines to create new machines that also contain copies of said genes. (The theory does have critics.)

Why does this matter? One reason is that the evolutionary process that led to my brain telling me that I have a “self” was a biased process. When I ask whether no self is fact or fiction, I’m trying to find truth. But the process leading to the creation of my brain wasn’t a process that was aimed at finding truth, it was aimed only at creating a brain that would be good at creating copies of the genes in that brain.

As Robert Trivers wrote in the Foreword to The Selfish Gene,

Natural selection has built us, and it is natural selection we must understand if we are to comprehend our own identities…

For example, if (as Dawkins argues) deceit is fundamental in animal communication, then there must be strong selection to spot deception and this ought, in turn, to select for a degree of self-deception, rendering some facts and motives unconscious so as not to betray – by the subtle signs of self-knowledge – the deception being practiced. Thus, the conventional view that natural selection favors nervous systems which produce ever more accurate images of the world must be a very naive view of mental evolution.

When we know someone is biased, we trust them a little less about the thing they’re biased about. A salesman is going to tell me all the best things about their product—their product is probably a little worse than what they’re actually telling me.

In the same way, the brain telling me that I have a self is biased towards coming up with answers like that. It wants me to center myself, not necessarily because it's true, but because it's an effective strategy for an organism to survive and ensure the genes in that brain make it to the next generation. When our brains tell us we have a self, we can't trust it—it's not an unbiased observer.

The title of the book can be read two ways—genes are selfish: they 'care' about themselves (Apologies to the biologists as I know I'm doing too much anthropomorphizing of non-human entities in this section!). But genes, in this theory, are also self-ish—in a way, it's genes that have a self, not the organism as a whole. They are the ones that have 'goals', and our bodies and minds (and the goals/sensations contained inside that mind) are just the puppets they've built to achieve those goals.

Another way you could think of the Selfish Gene hypothesis as implying no self is that it shows there isn't a consistent unity of purpose at the genetic level. You may argue "sure, maybe I'm just an organism programmed by evolution to have certain desires, but I'm still a self because I'm one organism united towards obtaining those desires"—but it turns out you would be wrong. Even those desires aren't always consistent on a genetic level. B chromosomes, for example, sometimes have effects that are maladaptive from the perspective of the organism, like having a negative effect on female fertility, according to Robert Wright in the book Nonzero.

[Caveat: a biologist friend who read a draft of this article said they aren't a fan of the selfish gene hypothesis. At first they suggested I delete the whole section, but they also pointed out that I could 'make many of the same points about the process of evolution in general, without mentioning selfish genes' (my paraphrase).

I'm lazy, so instead of rewriting the whole section, I'll add this reminder of what I said above: some parts of this essay are more convincing (and more scientifically certain) than others. This link, copied from earlier in this section, can give you an idea of what critics of the selfish gene hypothesis say.]

Physics

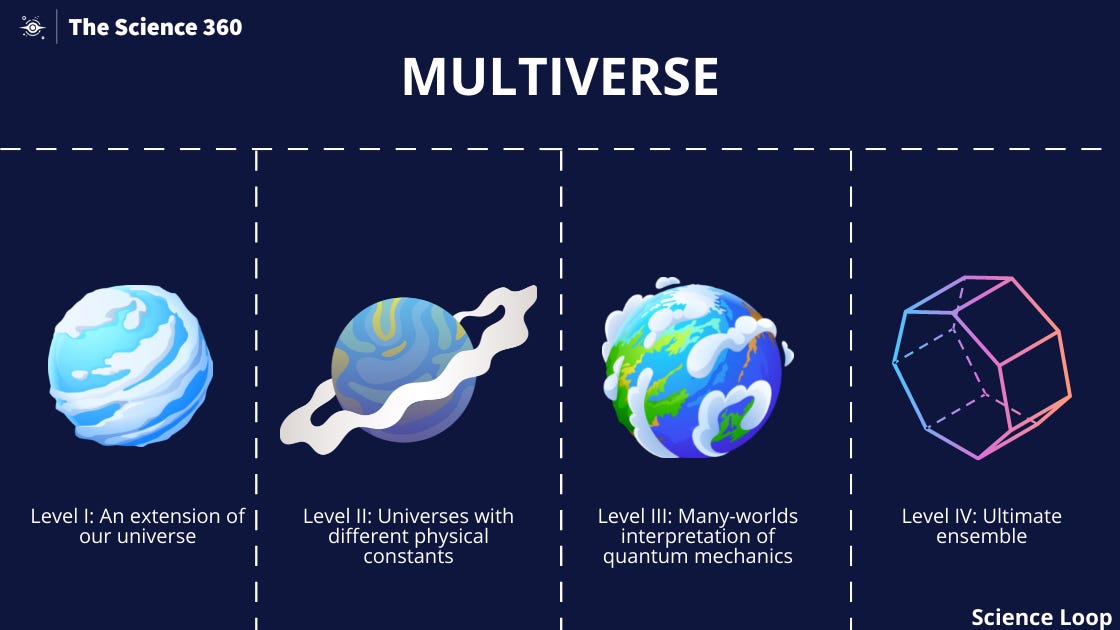

It’s a hypothesis of standard physics that the universe is infinitely large (though some physicists believe the universe is finite). It’s so large that, eventually, far enough away from Earth, there’s another point in space where everything is completely identical to here. The entire history of the observable universe (observable from that specific location) has been the same up to this point. You have no possible way of discerning whether you're on “that” Earth, or on “this” Earth.

Physicist Max Tegmark calls this concept the “Level I Multiverse”, and he estimated that such a location should exist within a distance of about (10^(10^115)) meters from our Earth. (A distance so large that I can’t even display it correctly in my word processor—a 1 followed by an unfathomable number of zeroes!)

In other words, in our universe, there is already another you, who’s had the same life and the same thoughts and learned all the same things in history class and sees all the same things when they look up at the sky. They’re just incredibly far away. Of course, there are also almost-copies of you scattered across our infinite universe as well. They’ve lived lives just slightly different from yours.

So, how do you know if you’re the you who’s here, or the one who’s way, way, way over there? Are both of these “you”? Normally, I think of me as my thoughts, and the shape of my body, and all of my lived experiences and relationships, etc etc. But in fact, that doesn’t define a unique me, since there are other collections of atoms, far, far away from here but still in our universe, that share all of those properties.

The “Level III Multiverse” is the 'parallel universes' concept that most of us are probably familiar with from recent popular culture. Another name for this concept is the Many Worlds Interpretation of quantum mechanics. An article in Quanta Magazine (that’s critical of the Many Worlds theory) describes it like this:

It is the most extraordinary, alluring and thought-provoking of all the ways in which quantum mechanics has been interpreted. In its most familiar guise, the many-worlds interpretation (MWI) suggests that we live in a near-infinity of universes, all superimposed in the same physical space but mutually isolated and evolving independently. In many of these universes there exist replicas of you and me, all but indistinguishable yet leading other lives.

If this theory is true, you are not just you, but rather there are infinite copies of you in parallel universes, who are all living different lives, ranging from being nearly indistinguishable from yours, to being so different from your life that they really aren’t you anymore. There are infinite selves, hence there is no self.

7. Atoms are empty (and there are gaps between them)

Although I wasn't a fan of the book The Power of Now, it did point out one scientific truth that I added to my list of examples of no self: we are empty. Like, really, really empty. In The Power of Now, Eckhart Tolle describes it like this:

Even seemingly solid matter, including your physical body, is nearly 100 percent empty space — so vast are the distances between the atoms compared to their size. What is more, even inside every atom there is mostly empty space.

An NPR article by a physics professor describes the emptiness of atoms themselves:

...electrons are a hundred thousand times farther from the nucleus than the nucleus's own width. If the nucleus were a beach ball in Midtown Manhattan, the electron would be living in an apartment in Philly.

And what does that mean? The atoms making up your chair — you know the ones supporting your booty right now — they are pretty much all empty space. Each one is a vast stretch of nothing that is lightly salted with an occasional fleck of stuff wandering in an endless void.

This site does the math for us: atoms are more than 99.9999% empty space. It’s wild that with all that emptiness, we still end up experiencing that there’s “something” here.

The Power of Now seems to be incorrect that the important emptiness is the distance between atoms. The main emptiness is emptiness of an atom itself. However, there is some emptiness “between” atoms too. In the Wikipedia article on Atomic Spacing, we can see that even the most dense and structured atomic arrangements are only ~75% atom, ~25% nothingness. (But again, that’s nothing compared to the >99.9999% emptiness inside individual atoms).

8. Free Will and the laws of physics

For me, and I assume for most people, part of our concept of having a "self" is feeling like I am the one in charge. Feeling like I make decisions about what I do next—in other words, that I have free will. And I definitely feel like I have free will, but there are some pretty strong arguments against it.

The concept of Determinism argues against free will. In simple terms, it says:

It sure seems like there are “laws of physics” that determine the behavior of the things in our universe, like atoms.

If these laws really are true, then the behavior of any collection of atoms has already been determined – just apply the laws of physics to the current arrangement of the atoms, and their future state can be calculated.

If this is the case, then everything in our universe has been “preordained” from the very beginning, and you and I are nothing more than a collection of atoms acting in accordance with the laws of physics.

Is there really a self if the collection of atoms that make up that “self” are just following the laws of physics, like every other collection of atoms in the universe? I think of a self as something that decides, that chooses. But if there's no free will, then there’s no deciding going on.

Neuroscience

Neuroscience experiments and brain disorders show us how easily we can become confused about our self-ness. I'm probably forgetting a few examples in this section, because there are just so many.

9. Your brain doesn’t know where your body ends

Most of us, on most days, have a pretty good idea of what is and isn't part of our body. But there are a number of examples of situations where our brain doesn’t know where our body ends.

The claim that "there is a self" implies to me that we should generally know what is or isn't part of that self. But it's surprisingly common to find cases where our brains can't correctly determine where our bodies start or end.

For example:

Phantom Limb Pain: People who lose a limb often feel very convincing “feelings” that the limb is still there. Wikipedia says that “Most (80% to 100%) amputees experience a phantom with some non-painful sensations. The amputee may feel very strongly that the phantom limb is still part of the body.”

Mirror-Touch Synesthesia: Some people feel things that are happening to someone else. I don’t mean “feel empathy”, I mean literally feel a physical sensation. They see someone else getting touched on the cheek (for example) and feel a touch on their own cheek. Wikipedia says that “Mirror-touch synesthesia is found in approximately 1.6–2.5% of the general population.”

The Rubber Hand Illusion: Put a rubber hand in front of someone where they can see it and ask them to try to imagine that it’s their own. Have them put their real hand on the other side of a divider where they can’t see it. Stroke the fingers of the rubber hand and the participant’s real hand with a brush at the same time. Then, suddenly, whack the rubber hand with a hammer. The participant will recoil like it’s their own hand being attacked, even though they can clearly see that it isn’t.

Somatoparaphrenia: From Wikipedia: "Somatoparaphrenia is a delusion where one denies ownership of a limb or an entire side of one's body. Even if provided with undeniable proof that the limb belongs to and is attached to their own body, the patient produces elaborate confabulations about whose limb it really is or how the limb ended up on their body. In some cases, delusions become so elaborate that a limb may be treated and cared for as if it were a separate being."

Although these are all somewhat rare examples, overall it’s clear we don’t always know where our own body ends.

10. Our memories are not very reliable

What is the self? One descriptor that I’ve already referred to is the idea that we are our experiences, thoughts, and memories. But: some of the things that we remember never actually happened to us. Our rough memories of events are usually pretty good, but we can easily be confused about the details. Here’s what Scientific American had to say in a 2010 article:

IN 1984 KIRK BLOODSWORTH was convicted of the rape and murder of a nine-year-old girl and sentenced to the gas chamber—an outcome that rested largely on the testimony of five eyewitnesses. After Bloodsworth served nine years in prison, DNA testing proved him to be innocent. Such devastating mistakes by eyewitnesses are not rare, according to a report by the Innocence Project... Since the 1990s, when DNA testing was first introduced, Innocence Project researchers have reported that 73 percent of the 239 convictions overturned through DNA testing were based on eyewitness testimony. One third of these overturned cases rested on the testimony of two or more mistaken eyewitnesses. How could so many eyewitnesses be wrong?

Elizabeth Loftus is the researcher most known for investigating the malleability of memory. In her "lost in the mall" experiment, about 25% of the participants were made to 'remember' childhood memories that didn't happen to them. Another study she co-authored gave people false memories of food-related experiences that changed their future behavior. From the paper's abstract:

False memories, or memories for events that never occurred, have been documented in the real world and in the laboratory...[In this study, we] show how false memories for food-related experiences (e.g., becoming ill after eating egg salad) can lead to attitudinal and behavioral consequences (e.g., lowered self-reported preference for and decreased consumption of egg salad).

Many experiments have confirmed that our memories are just not that good. If I define my 'self' as the 'me' who experienced, X, Y, and Z, the reality is that I'm not exactly the me that I think I am. Do I really not like cherries, or is it all just a mixed-up memory that never happened to me?

11. Split brain experiments

The term 'split brain', according to a 2020 paper, refers to "patients in whom the corpus callosum has been cut for the alleviation of medically intractable epilepsy." Very roughly speaking, this procedure severs the link between the left and right sides of the brain.

Patients who have undergone this procedure live more-or-less normal lives. (An article linked later in this section says "After giving the patients a series of assessments—an I.Q. test, a memory test, motor-skills assessments, and interviews—[a researcher] reported that most of the patients had the same levels of cognitive functioning after the surgery as before, and displayed no behavioral or personality changes.")

However, some split brain patients show a variety of intriguing behaviors when tested in experiments that isolate the left and right sides of their body (for example, with a divider between their eyes so they can only see an object with one eye).

Here's an example from the paper linked above:

In a particularly dramatic recorded demonstration, the famous patient “Joe” was able to draw a cowboy hat with his left hand in response to the word “Texas” presented in his left visual half field. His commentary (produced by the verbal left hemisphere) showed a complete absence of insight into why his left hand had drawn this cowboy hat.

Or another example from an article in The Atlantic:

In one set of studies conducted in 1962 and 1963, Gazzaniga presented Jenkins with four multicolored blocks. Then, he showed Jenkins a picture of the blocks arranged in a certain order, and asked him to make the same arrangement with the blocks in front of him.

Because the right brain handles visual-motor capacity, Gazzaniga was unsurprised to see that Jenkins’ right hemisphere excelled at this task: Using his left hand, Jenkins was immediately able to arrange the blocks correctly. But when he tried to do the very same task with his right hand, he couldn’t. He failed, badly.

“It couldn’t even get the overall organization of how the blocks should be positioned, in a 2x2 square,” Gazzaniga later wrote of Jenkins’ left hemisphere in his memoir, Tales from Both Sides of the Brain. “It just as often would arrange them in a 3+1 shape.”

But more surprising was this: As the right hand kept trying to get the blocks to match up to the picture, the more capable left hand would creep over to the right hand to intervene, as if it realized how incompetent the right hand was. This occurred so frequently that Gazzaniga eventually asked Jenkins to sit on his left hand so it wouldn’t butt in.

The paper links above asks: Does a split-brain harbor a split consciousness or is consciousness unified?

They provide their answer in the next sentence: The current consensus is that the body of evidence is insufficient to answer this question.

Do split brain patients have two consciousnesses? Do we all have two (or more) consciousnesses which are just barely integrated enough to convince us we're a unified self, but easily separated by a minor brain surgery? If we one day figure out how to do human brain transplants, and you transplanted half of your brain into another person, would you become two selves?

Final thoughts

In summary: we are beings who are 99.9%+ empty space—and a good portion of what remains is bacteria that doesn't share our genes. There may be infinite copies of us, in parallel universes and/or unfathomably far away in this universe. Our cells are constantly being replaced, our behavior can be influenced by parasites, some of our memories didn't happen the way we remember them, and our brain can be easily tricked into not knowing where our bodies end.

I think my understanding of Buddhism and no self has made me a kinder, humbler person. If my memories are wrong, I should be nicer to people I disagree with. If my desires are a result of my self-ish DNA, maybe I should trust those desires a little less. If there's no free will, there's no reason to get upset at others when they annoy me. And in a universe of unfathomable size, I am nothing special.

Update (2024-05-10): Here’s an interesting article I came across today:

The fusion of two sisters into a single woman suggests that human identity is not in our DNA.

You might say this is the “genes do not define the uniqueness of a person” argument (to use a quote from the article).

Selected Reading:

Robert Wright, Why Buddhism is True

Matt Ridley, The Red Queen

Max Tegmark, Our Mathematical Universe

Derek Parfit, Reasons and Persons

Richard Dawkins, The Selfish Gene

And a few more selected readings that didn't make it into the article:

Good interesting post and I kind of get it (Psychologically) . But how does this knowledge benefit or change my life in any way ? (I don't intend for a negative comment , I studied Buddhism for years and this topic of the self always frustrated "me" )

Fun. I enjoy this physical and philosophical debate and have often pondered the free will part of it. Hard to explain but the ship of Theseus part I am ok with. I think the unknowable is a “correct” definition of self. I know I am a kind of self, but I don’t think I can ever fully scientifically define what that is. It being a changing thing is part of the problem. But I still land on their being a self with a quantum mechanics mind of caveat: at all times we are a superposition of many states, some of them very self like and some not. In moments of consciousness, we are usually collapsing the wave function enough to reliably identify ourselves there perceiving the Universe, at modest resolution. this does not invalidate the existence of not self.