[This essay spoils Season 1, Episode 14 of the Netflix show Love, Death & Robots. Each episode of the show is an independent story (like Black Mirror) so it doesn't spoil any other episodes.]

In Throw a whole lot, I wrote that you need to practice throwing a lot if you want to be an elite player—but you also need to find the right mentality to practice throwing that much and stay sane. This article explains one of the techniques I use to stay sane and avoid burnout.

I've always found that reading about mental states can be very hit or miss. Some people think The Subtle Art of Not Giving A Fuck is a life-changing book, and other people think it's worthless and badly written. Not all advice is right for everyone at every moment. The thing that clicks is a unique result of where someone is at that moment in life. Most of you might find this essay worthless but I hope it works for one or two of you.

Zima Blue

In the Love, Death & Robots episode "Zima Blue", Zima is a brilliant artist famous across the galaxy—and he's an AI in a metallic humanoid body. He invites a number of spectators to his residence where he's planning to unveil a new work that's the culmination of his artistic career. Before the unveiling, he agrees to be interviewed by a reporter.

During the interview, he reveals his previously unknown origins. He wasn't a human whose consciousness was uploaded into an immortal machine, nor was he an AI programmed in a research center. He began life as a little pool-cleaning robot, a Roomba for pools, whose owners successively programmed more and more features until he one day became sentient.

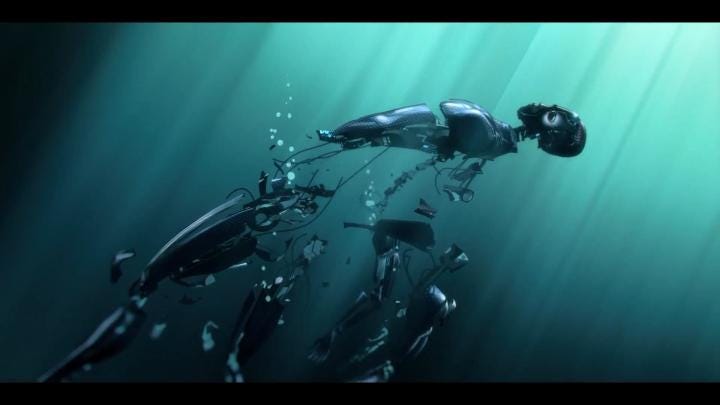

The next day, the spectators gather for the unveiling. Zima walks up on stage, takes off his coat...and dives into his pool, where he sheds his humanoid body and sentience and returns to his original Roomba-shaped form and his simple programming, wanting nothing more than to clean pools for the rest of time.

Fulfillment and simple duties

I think most of us feel the pull of living a simple life. Whether we choose to lay on the beach all day, or head to an off-the-grid cabin in the hills, a break from complication can be nice.

Given that I write this blog, you can probably guess that I'm someone who likes thinking. It can be fun to write a good essay, learn a language, play a complicated board game, or solve a coding problem. There's a joy there when all the pieces click and you can see how the whole system fits together—whether that system is an essay or the arrangement of players on a frisbee field. Complicated can be fun.

Besides fun, I also think it's morally important to engage with our complicated world. Our world has climate change, hunger, death, injustice and too many other imperfections to name. Those problems are way too big for any one of us to fix, but I believe we all have a duty to do what we can to make things better instead of worse.

The butter-passing robot is dismayed to find out that its only purpose in life is to pass butter. And that's reasonable — it's nice to fulfill our potential and use our abilities to their fullest extent. Frisbee is just one part of my life, and without complication life would be too dull.

But to stay sane, we need to step away from all that sometimes too. Like in Zima Blue, it can be really nice to adopt a simple mindset of doing one thing and doing it well. Going to the beach is one way to escape from a complicated world, but I think there's a reason Zima chose to clean the pool and not lounge at the pool. There's a certain beauty in doing something simple and doing it well.

That's my mindset when I go out and throw the frisbee day after day. During the rest of the day, I can think complicated thoughts. I can worry about America's housing crisis, I can play complicated strategy games, I can worry about whether I'm using my potential to its fullest and doing all I can to prevent climate change and reduce the amount of trash I create.

But for a little while every day, I go into Zima Blue mode. I'm not that complicated person anymore. My only purpose is to throw frisbees. It's not the be-all-end-all of life, but there's a certain joy that comes from fulfilling that simple duty.

To put it another way, when we talk (sports) psychology, there's maybe this assumption that psychology equals complicated. An assumption that you have to get these different little parts of your brain all pointed in the same direction and convinced of the same goal before you can reach your potential as an athlete. But I think we should sometimes go for simplicity instead. I throw frisbees. It's good. Don't overthink it.