Cool it with the cool downs

The science says they're not doing much

The topic of cool downs came up at practice this week and I promised my team I'd do a little research and get back to them. I'll share with you all what I shared with them.

A 2018 meta-analysis looked at the research around active cooldowns. It found that they were largely ineffective:

Most evidence indicates that active cool-downs do not significantly reduce muscle soreness, or improve the recovery of indirect markers of muscle damage, neuromuscular contractile properties, musculotendinous stiffness, range of motion, systemic hormonal concentrations, or measures of psychological recovery. It can also interfere with muscle glycogen resynthesis. In summary, based on the empirical evidence currently available, active cool-downs are largely ineffective for improving most psychophysiological markers of post-exercise recovery, but may nevertheless offer some benefits compared with a passive cool-down.

It doesn't help your performance in the following days:

Conflicting findings have been reported with regard to the effects of an active cool-down on next-day(s) performance, with some studies reporting small to moderate magnitude benefits of an active cool-down compared with a passive cool-down, and others reporting trivial effects or small decreases

It may help lower your blood lactate levels, but that doesn't actually mean anything. Lactic acid isn't what makes your muscles sore the day after a workout:

In summary, compared with a passive cool-down, an active cool-down generally leads to a faster removal of blood lactate when the intensity of the exercise is low to moderate. However, the practical relevance of this effect is questionable. Lactate is not necessarily removed more rapidly from muscle tissue with an active cool-down.

It doesn't help you avoid muscle soreness the next day, nor does it help with general feelings of stiffness in the days following a workout:

The scientific evidence available suggests that an active cool-down does not significantly attenuate the decrease in range of motion and perceived physical flexibility, or attenuate the increase in musculotendinous stiffness up to 72 h after exercise

It doesn't help your immune system recover faster after a tough workout:

...two other studies reported no significant difference between an active cool-down and passive cool-down on immune system markers 24 h after a soccer and rugby match.

Another blog post covering the same paper says "there is one thing that scientists agree upon: cooling down may help prevent possible dizziness you may experience after really intense exercise." But even that isn’t clear from the paper, as far as I can tell (And what does it even mean that scientists agree it "may" help?):

active cool-down has been reported to result in a higher blood flow to the legs and forearm, but whether these effects prevent post-exercise syncope [i.e. feelings of lightheadedness] and cardiovascular complications remains unknown.

So what about the end of that first quote at the top of this article—that active cooldowns "may nevertheless offer some benefits compared with a passive cool-down." Personally, my intuition is that any positive results fall into one of two categories. The first are results that are subject to the "green jelly bean fallacy", made famous by XKCD. If you do 20 studies, you shouldn't be surprised that 1-of-20 ends up with a 5% "significant" result—and this meta-analysis looks at over 100 studies.

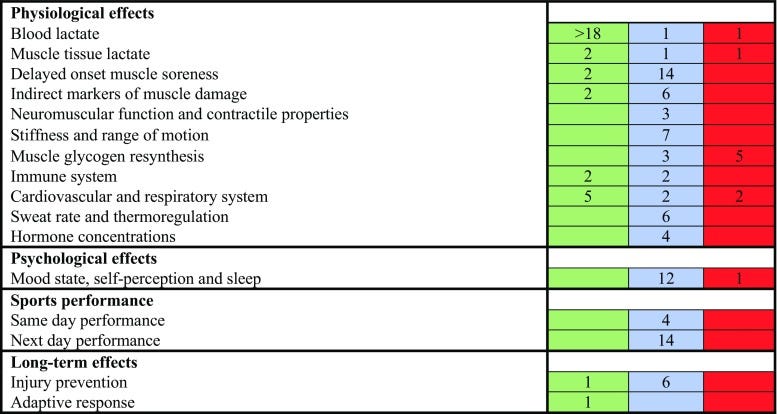

The other positive results are studies that measure one specific small output variable that's not clearly relevant to what we're trying to achieve. The study authors include this table summarizing the studies they've analyzed. The number in each box represents how many studies are in that category. Green results are positive benefits, blue are trivial/neutral outcomes, and red are studies that showed an active cool down to be harmful:

Cool downs help lower blood lactate levels right after exercise, but there are two problems with this finding. First, regardless of myths you may have heard growing up, there's no clear evidence we should ever care about blood lactate levels for recovery. And second, what we really care about is recovery in the following days, so a measurement taken 30 minutes after exercise doesn't necessarily prove anything.

Aside from blood lactate levels, all other categories have about as many combined results in the trivial+harmful categories as in the beneficial category.

This study wasn't surprising to me, given some of the similar sports science myths I wrote about in Sports science findings you should know. If you do find yourself still attracted to cooldowns, I'd encourage you to think about why, specifically, you'd expect them to be effective.

The micro tears in your muscles won't become less-micro-torn by doing an extra workout at the end of your workout. Does something magical happen when your heart rate decreases slowly instead of quickly? And if so, shouldn't standing or sitting still on the sidelines when you're not in the game be even more harmful than skipping an active cooldown?

All that being said, there are benefits to having rituals you believe in. If you have a cooldown ritual you really like, there’s no need to give it up.

My one suggestion is that when you're back at home after your workout, you never want to be sitting around *completely still* for many hours at a time. Get up and get a little light activity on the regular. Blood flow is what brings the nutrients and such that help your body repair itself. (This part of the logic of cool downs is sound—a little activity does help our blood flow. But when we need that circulation most isn't immediately after a workout—our blood is still flowing quite well at that point.) For more on this, I suggest the books Good To Go and Exercised.