X+Y is by Eugenia Cheng. The subtitle is "A Mathematician’s Manifesto for Rethinking Gender". I had some high hopes about this book—a book about gender by someone who thinks like me! Overall I was a little disappointed from those high hopes, but not that disappointed: it was still a pretty good book about gender.

She has two main points that she makes. One of them is non-mathematical: she suggests that we stop using gendered terms to describe personalities. We shouldn't say things like "a masculine person" or "a feminine person". Everybody is a little bit different. Everything is a spectrum. Lots of men have traits that we sometimes call feminine and lots of women have traits that we often call "masculine". She proposes using the terms "congressive" and "ingressive" to describe certain personality types. Very roughly, ingressive is a replacement for the term masculine and congressive replaces the term feminine.

As she puts it:

The etymological idea is that “ingressive” is about going into things, and “congressive” is about bringing things together...

ingressive: focusing on oneself over society and community, imposing on people more than taking others into account, emphasizing independence and individualism, more competitive and adversarial than collaborative, tending toward selective or single-track thought processes

congressive: focusing on society and community over self, taking others into account more than imposing on them, emphasizing interdependence and interconnectedness, more collaborative and cooperative than competitive, tending toward circumspect thought processes

Side note: befitting a mathematician, she's great at seeing the shades of gray instead of seeing a situation as black and white, as in this example:

Men Are from Mars, Women Are from Venus by John Gray is a famous and divisive example, but I actually found it rather useful...I take the book to be really saying, “Some people, in some situations, are from Mars, and others, in other situations, are from Venus, and it’s often men who are one and women who are the other but not necessarily, and you might be both at different times in different situations.” That is a somewhat less catchy title.

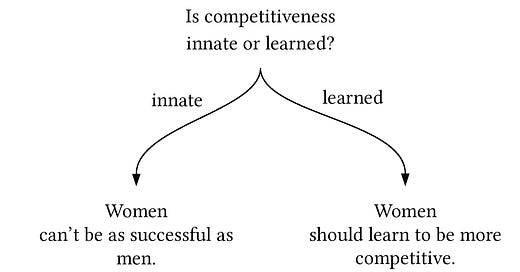

The second main point of the book is more "mathematical". Essentially, she uses an analogy with her field of math to dig into the hidden assumptions that often trip us up when talking about gender. So combining these two main themes, we might start with a wrong idea like this (all images are from the book):

What's wrong about this? There's a hidden assumption — that being competitive is good. It's something our society currently values, but society could be arranged in different ways:

In the general case,

The best example she gives of why society could be re-arranged to be more equal, more cooperative, and more productive is in her field, mathematics. The way math is taught to children doesn't have much in common with what professional mathematicians do. A lot of people have math stress. We have math "Olympiads" that teach people how to do... some sort of problem solving under stressful conditions:

A marker of “success” at an earlier stage in mathematics is the International Mathematical Olympiad, an international math competition for high school students. The training that some of these youngsters undergo for this competition is arguably as intense as training for the actual Olympics. And it is not that rare for the winning team to be all boys. According to the website FiveThirtyEight, in the history of US participation in the event (beginning in 1974), 88 percent of its six-person teams have been entirely male. The United States won in 2018, 2016, and 2015 with all-male teams each time. (In 2017 South Korea won and had one female team member.)

But again, this isn't what a person like Dr Cheng who researches math does: they have all the time they need to think about problems and discuss them with others and eventually come up with some concept we've never seen before. Being smart enough to do a Math Olympiad probably has some correlation with having the kind of mind it takes to do original work in math, but there's also a big enough difference that we could be losing lots of potential mathematicians to "math stress".

Competition

In addition to the math Olympiad mentioned above, there is a lot of discussion of competition, and how our society is too focused on competition to its own detriment:

...Alfie Kohn characterizes competition as something that happens when resources are scarce. From here we get the idea that competition is a “natural” behavior, because “in nature” resources are scarce and so we have to compete for them. The thing is that, as with education, in many situations in modern life there isn’t any real expendable resource at play, but a scarcity is fabricated in order to create artificial competition...

And so things are made into a competition by contriving a scarcity. Children are put into music competitions in order to rank them even though playing music well is not a limited resource. They are put into math competitions, spelling competitions, general-knowledge competitions. It is said that this makes it “fun.” But it only makes it fun for children who like competition, and plenty don’t, including me.

The Math Olympiad makes a competition out of being good at math. But math skill isn't a scarce resource...everyone can be good at math. (Well, maybe. Perhaps if we all got better at math, our collective definition of being "good" at math would change.) She describes a musical community that she's part of:

It is less like performing (which is ingressive) and more like sharing music we love (which is congressive). There is no emphasis on perfection or correctness (which is ingressive). The pressure of performance on a stage is completely removed, and this can result in more emotionally touching music. But it’s also more efficient, because when you’re preparing for a performance a huge proportion of the work goes into preparing to withstand stressful conditions.

And suggests that competition is harmful to other values we care about: "Competition obstructs collaboration". Finally, the book ends with a final quote about competition:

Things don’t always have to be a competition, but perhaps if there is only one competition, it is between the ingressive and congressive forces in humanity. I hope that we will choose congressivity and work together, congressively, to build a better future for everyone.

This is something I'm interested in writing about more at some point. I'll add a few initial thoughts here. First, I agree that there can easily be negative-reinforcement cycles of competition — almost-perfect music can be a beautiful experience, too, and perhaps we 'waste' too much time training performers who are 99.9% perfect instead of 99% perfect, or waste time training performers to acclimate to stress instead of putting them in situations where they can feel relaxed. This is roughly an example of "Moloch", or a Red Queen's Race, where we have to work harder and harder just to stay in place. If we all could just agree to take it easy, no one would have to work so hard. But everyone would selfishly benefit from "defecting" from that agreement and working hard and getting rich while others relaxed and ended up (relatively) poorer.

But, at the same time, I have trouble agreeing completely. There are definitely examples where perfection is beneficial to us — I definitely appreciate that the ball-bearings in bikes, cars, and buses are perfectly round and not just sort-of round. There are even examples in art, I'm sure. We all benefit from experiencing extra beauty through innovation when the pictures that we take have ever-higher definition, right? Her musical community is awesome, but I think one reason it succeeds is that people are well-trained enough that the music actually sounds good instead of bad.

Now, I just wrote positively of how companies competing has brought us beneficial 'perfection'. But at the same time, I'm a post-scarcity economy kind of guy — the economy is becoming more and more based on "artificial" scarcity, as (1) we get better and better at making things (food, housing, etc) more efficiently and (2) more and more of our economy becomes information-based, which is almost always artificial scarcity (I could just copy-and-paste a copy of a Hollywood movie for you...except that's illegal!)

And I'm an Against Intellectual Monopoly kind of guy. In my reading, intellectual property reform is at the same time both congressive and ingressive at the same time:

The idea behind patents and trademarks is that people are incentivized to create things by the money they can earn through having a monopoly on selling their creation. Assuming people will be motivated mainly by their own selfish interests is ingressive, so the idea of getting rid of patents and copyrights is congressive in that sense.

But, patents and copyright create a monopoly, which is anti-competitive. In a world without intellectual property, companies would have to relentlessly compete, instead of resting on the laurels of one great invention. In that sense, getting rid of intellectual monopoly is ingressive.

Intellectual monopoly also stops one inventor from building off of the ideas of a previous invention. Without intellectual monopoly, I would be able to take your good idea, and make it even better. In that sense, getting rid of patents encourages congressive collaboration.

Intellectual monopoly also generates competitive "waste" — like pharmaceutical companies who invent "copycat" drugs that have the same effect of an already-existing drug but work through a slightly different chemical effect and so are not restricted under the original chemical's patent. This is a bit like the point that Cheng makes — that performers "waste time" getting good at dealing with stress, when in a hypothetical world without stress, they could focus purely on performing. In a world without patents, companies could focus purely on finding drugs to combat new diseases, instead of every different company wastefully finding a different way to combat the same disease.

As in the first quote, Cheng distinguishes between "real" scarcity (I either buy one company's bike or another's, I'm not going to buy two bikes) and "artificial" scarcity (One musician being good doesn't stop another musician from being good, too). And intellectual monopoly is artificial scarcity: Since I can't drive a car to the grocery store at the same time you drive the same car to the gym across town, the car itself has "real" scarcity. But me having the knowledge of how to build a car doesn't prevent you from having the same knowledge. In fact, its so artificial that we only have this scarcity because we've used laws to create it.

I think this is an interesting example because it shows that competition and collaboration are not always even opposing concepts — getting rid of IP laws would increase the amount companies need to compete while at the same time would encourage them to collaborate more (in some senses).

I think one factor in the way I look at competition-vs-collaboration is the concept of slack. Slack is:

Slack. The absence of binding constraints on behavior...

Slack means margin for error. You can relax.

Slack allows pursuing opportunities. You can explore. You can trade.

Slack prevents desperation. You can avoid bad trades and wait for better spots. You can be efficient.

What does this have to do with competition and collaboration? Having slack can defeat unhealthy competition — if you need to make a wage so your starving child can eat, you'll do just about anything. When you don't have this, or other, binding constraints, competition-as-survival can turn into competition-as-fun or competition-as-fulfillment.

Another way to say it is that there might be two different levels, one where competition is happening (for example, companies compete against each other to make a better product) and another where collaboration is happening, perhaps the level below (workers at a particular company collaborate) and/or at the level above (society provides a social safety net so workers at a company that gets out-competed aren't left penniless).

It goes back to the question first quoted from X+Y, of whether competition is "natural", since we evolved in a world of scarce resources. If people are naturally motivated (to some extent) to do things that will help better themselves, then we may want to encourage a certain level of competition in society, to get the most out of people. My intuition is that humans do have a certain level of "innate selfishness", that can be harnessed to make society better. But if humans aren't competitive by nature, and our ingressiveness is all cultural, then we could try to create a culture that's fully cooperative.

Sports are another area, near and dear to my heart, where the scarcity is real and not artificial. I do try to approach sports with this "two-level" approach. The competition level is the one where I do my best to win in a particular game. But then I also have a "collaboration" level, where I'll talk strategy, tips, and feedback with anyone, including the other team — I want to help everyone get better, not just people on my team, so we can all better fulfill our human potential and have games that are even more fun in the future, when we are more skilled than we are now. And I do think sports are "more fun" when you're better.

Even if both situations end with my team winning, I'm happier after the game if both teams played hard, were evenly matched and made brilliant plays. Even if both situations end in a turnover for my team, I feel happier if the situation was "I made a great throw, but the defense made an even better play" than if I threw a totally inaccurate pass. It seems close to universally agreed that competition is more fun against a well-matched opponent. It's not so fun to blow out the other team, and it certainly isn't fun to get blown out. You could even call this vulnerability: a chance you'll lose, the state of taking a trip into the unknown. I think this fact of competition only being fun against evenly-matched opponents has a role to play in a theory of "healthy competition".

Why would I rather feel skilled but lose, than win against far inferior competition? One article I read recently argues that this is because mastery is an innately fulfilling experience:

For a study published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, psychologist Carol Ryff surveyed more than 300 men and women, in order to identify correlates of well-being. She found that people who had “a feeling of continued development,” and saw themselves as “growing and expanding” were more likely to score high on assessments of life satisfaction and self-esteem than those who did not. Other research shows that when people throw themselves into an activity for the sake of the activity itself — and not for some sort of external reward, like money or fame or Instagram followers — they tend to report long-term well-being and fulfillment.

I'd interpret this as a mix of ingressive (chasing mastery, continuing to develop) and congressive (doing it for the sake of activity itself instead of money and fame) factors.

Another concept that I've used over the years is comparing myself to my past self, instead of comparing myself to others. It's still a "competition", but I've always found it to be more psychologically healthy. I guess you can argue that comparing yourself to others is an "artificial" competition (everyone has different histories and challenges and genetic gifts, so it will never be an apples-to-apples comparison), while comparing yourself to who you were a month ago is a non-zero-sum game: me getting first place means you can't also be in first place, but me getting better at something doesn't stop you from also getting better at the same thing.

Overall, I think that if achieving mastery is healthy for us, then competition has healthy aspects, too. It helps us notice where we're still weak and gives us a way to measure our progress.

I wrote above that I think comparing myself to my past self, which sounds very inwardly focused (ingressive) is much healthier than comparing myself to others, which is congressive in the sense that it involves others, but feels much less healthy. Cheng spends a bit of the book talking about self-confidence, and I connect that back to competition, a little bit, and to this reversal where a more ingressive outlook is a healthier one. She says:

Self-confidence that comes from external validation could be thought of as a congressive form of self-confidence, but the very concept of “self-confidence” sounds ingressive and might put congressive people off; it definitely put me off in the past.

In other words, we want our confidence to be grounded in something, instead of being all in our heads. But doesn't the phrase "external validation" just start ringing those alarm bells about healthy self-image? This case leads to another aspect of why competition might be stressful for some people: their self-image is internally focused, and they want to tell themselves, I'm perfect, I'm great, I'm a boss. In competition, we're vulnerable, and we're liable to find out that we're not as great as we want to pretend we are.

My healthy approach to competition works hand-in-hand with a healthy approach to self-image. I know I'm not perfect, and I fully accept that, so I'm not scared of going into competition and finding out that I'm not all that. I already know I'm not all that, so I can go and compete without risking a negative shock to my self-esteem. Cheng sees it as based in external validation, but I think what we really need here is just accurate self-image.

Another important take on competition is the book Finite and Infinite Games, by James Carse.

A “finite game” is pretty much a game, as we usually use the word: there’s a start and end point, with set players and set rules. There’s winners and losers. An “infinite game” is taking part in the type of “play” that has no start point and no end point. Roughly, I think of this as “taking part in culture”. “A finite game is played for the purpose of winning, an infinite game for the purpose of continuing the play”. So for me, to go back to the example of sports, playing a particular game of frisbee is a Finite Game, but helping my friends get better so everyone can have more fun in the future is the Infinite Game.

One thing I've heard people say turns them off from sports like ultimate frisbee is the idea, not of losing the competition, but of letting their teammates down. What to think of this? In one way, I see this as an ingressive outlook, i.e., it's shying away from collaboration. And again, this is another area where collaboration (with teammates) and competition (against opponents) happens on different levels. In sports, where we play a game that is defined by competition, the competition enhances the collaboration — people come together and build a community (team) in order to more effectively compete. But perhaps in "real world" situations (solving global hunger?) people can come together to the same extent with needing to compete against another group of people.

In Ultralearning (a very ingressive book title, no?), Scott Young relates a story about Scrabble champion Nigel Richards. Richards's Wikipedia page begins with this sentence: "Nigel Richards (born 1967) is a New Zealand–Malaysian Scrabble player who is widely regarded as the greatest tournament-Scrabble player of all time." So, certainly someone who has the ingressive/competitive bona fides. So how does he feel about playing Scrabble? Like this:

A fellow competitor, Bob Felt, bumping into Richards at a tournament noted his monklike serenity, telling him “When I see you, I can never tell whether you’ve won or lost.” “That’s because I don’t care” was Richard’s monotone response.

Which is not to say that there aren't other champions (like Michael Jordan) who are known for being intensely competitive in the traditional sense. I think Richards's quote brings us back to slack — perhaps another definition of slack is "having no choice but to care". If you have no choice but to care, you end up in a situation of competition-is-stress. If you have the slack to not care, you can reach the level of competition-as-fulfillment.

Richards is apparently someone who doesn't talk to the media much, so we don't know exactly what he meant by that quote. One possibility is he "doesn't care" about winning or losing because he, as I've suggested, compares himself to himself instead of to others. It's also possible that he just meant that Scrabble is like a "day job" for him, and he finds meaning and validation in other areas of his life.

One aspect of competitive situations that Cheng doesn't touch upon is that competition often happens with people watching us. People often feel stressed in public situations, even when there is no competition actively happening — like giving a presentation at work. Is giving a musical performance stressful because we're being compared to others, or is it stressful because there are people watching us, and that's innately stressful for many people?

Similarly, just as "competition is good" is perhaps partly culturally programmed, "competition is stressful" may be culturally programmed, as well. Cheng's examples involve kids learning to be stressed from an early age. But why? As Cheng asks about many other qualities in X+Y, is that nature or nurture? Is it biology or culture? Could we make the world more 'healthily competitive' by teaching our kids to have a better outlook on competition? This would solve some of Cheng's objections to fabricated scarcity, but not all of them: there still may be people who are amazing at real math who are turned off from math by "speed math" competitions.

I also stress that this starts in childhood because kids are just kids. Their brains aren't fully developed. Lots of kids don't like vegetables, but then grow out of that stage as they mature and their relationship with vegetables changes. Perhaps the same thing would happen with competition, if people weren't so averse to it that they avoid it completely as adults.

Finally, I can't help but connect the question of competition to the "everything is a status game" hypothesis. Do I just like competition because I'm good at it? Sure, I can say I want everyone to get better at frisbee, too, but would I still feel that way if I was the one who was the worst at it? One reason I don't think this is fully true is that, as mentioned above, it does feel more fun to win a game where I'm challenged and forced to work my hardest than to win a game where I don't even have to try. Another argument against it is that, in the big picture, I'm not the best. There are professional athletes out there who are way, way better at their sport than I am. So I do think it's possible to create a world that's much less hierarchical, and we're not always doomed to find some new way to rank people whenever the old way of ranking them stops making a strong hierarchy.

Similarly, Cheng points out that, in a way, being "less manly" is actually "more manly":

Arguably that type of need for feelings of superiority stems from deep insecurity—the opposite of self-esteem. Perhaps in that case it actually takes more self-esteem to be congressive and not need that feeling of superiority.

To bring it back to the example of sports, being open to teach others all of my tricks is a way of winning the status game, still: it's like saying I'm strong, and I'm secure, and I'm so un-scared that I'll happily teach you all my tricks and then still compete against you. I prefer to believe that I'm truly not playing status games, and I've risen above that, but perhaps there really is a little bit of that line of thinking in the back of my mind.