32 Seconds of Cal Nightingale continuation cutting genius

A case study in attacking awareness

I'm going to show you 321 seconds of a guy on offense not even touching the disc...but it's going to be some of the smartest cutting you'll ever see.

I was re-watching some clips of Brown University's 2024 national championship run for another potential future article, and I was struck by Brown's Cal Nightingale, and his probing cuts playing off Brown's dominator motion in the final moments of Brown's semifinal win over Colorado.

Click here to watch on YouTube, or play the video below to see the relevant moments. Cal is the Brown player who starts the clip at the "front of the stack"2:

Here’s the video:

Let's get into the weeds on what happened here.

0. Bouncing around in readiness [the whole time]

The first thing that stands out is just how locked in he is the entire time. Hive Ultimate calls inactivity one of the biggest offensive mistakes, and I myself (eg Always be offering) and others have certainly written about similar topics as well.

Just look at how Cal is bouncing around nonstop, ready to engage at a moment's notice, and constantly adjusting his position as the disc and his teammates move.

I don't think you *have* to be literally bouncing to be mentally engaged. As an old guy myself I tend to be less obviously active (but just as locked in mentally) in these "off ball" situations, but the bouncing works well as a sign of how keyed in he is.

I. Holding off on the clogged upline continuation [0:05]

Before we get going...for anyone who doesn't know them, here are this post's other three co-stars—Leo Gordon, Jacques Nissen, and Elliott Rosenberg—who'll touch the disc in Brown's dominator-esque offense:

I'll call them by their last names from here on out.

After a stoppage, Gordon brings the disc into play by immediately throwing a backhand to Nissen. There's nothing too special to say here (we'll get to that in a moment), but Cal does a good job being aware of a teammate who's still in the space Cal would like to attack for a continuation upline cut. Cal makes the right decision to hold off on cutting, and Nissen looks to swing the disc.

II. Holding off on the swing continuation when Jacques has steps [0:10]

Nissen throws the backhand swing to Rosenberg. Cal clearly has an opportunity to attack the space for a second swing pass—and in many offenses he would be expected to—but he notices Nissen has steps on his defender after a throw and go. So he holds off on attacking himself, and lets Nissen continue into the space.

I've written about this idea before—Let your teammates be open. I like to think that if Nissen didn't have steps, Cal and Nissen would have both seen that and adapted—Nissen by slowing down and Cal by choosing to engage as the active cutter himself.

Again, I'm not saying this is the world's most brilliant read, but it's not uncommon for a player to miss a teammate cutting into the same space they think they have an opportunity to attack. For example, see this sequence from a game that happened just earlier today:

III. Attacking in response to Rosenberg's pivot, then aborting [0:14]

OK, now we're getting into the stuff that I think is really high level. Rosenberg has the disc, and he chooses not to throw to Nissen's throw and go cut. He then looks to Gordon on his forehand side, but chooses not to throw that, either.

What happens next is one of my favorite parts of this sequence. Rosenberg starts pivoting back to his (and our) left. Cal sees Rosenberg start to pivot, and he sees the open downfield space that Roseberg is pivoting towards, and immediately starts to attack it.

But then, Cal sees that instead of looking downfield towards him, Rosenberg has gone straight to looking to Nissen for a reset. Cal recognizes this, too, and he ends up pulling out of his cut nearly as soon as he's started it.

All you end up seeing is Cal bending his knees slightly and taking two somewhat hard steps towards the space before straightening back up again. But in order to do that he needed to be aware of the open space, aware of what his thrower is—and isn't—paying attention to, and ready to attack the available space at the moment the thrower's attention shifts.

Rosenberg doesn't look at him, but I think this is a good read by Cal and a slightly suboptimal read by Rosenberg3. And it's smart of Cal to not waste energy (and clog space) on a good cut that the thrower has chosen not to consider. Him continuing to attack with Rosenberg not looking wouldn't help anything...so he doesn't.

I grabbed a clip of this one in slo-mo to hopefully make it a little easier to catch the subtle go-then-abort:

IV. Sliding to force the full faceguard [0:23]

Rosenberg eventually completes the reset pass to Nissen that he wanted. As Nissen looks for an option and Leo Gordon dances around, Cal subtly sets himself up for success.

One of the first few frisbee-related posts I wrote on this blog was about making it hard for your defender to see both you and the disc:

...even when you defenders are in optimal position, you can constantly make their job more of a hassle by walking out of their blind spot and forcing them to choose whether they want to be able to see you or see the disc.

Cal does this perfectly here. With the defender looking over their right shoulder to keep an eye on the disc, Cal slides a step towards the defender's left shoulder, forcing them into a choice: lose track of the disc, or lose track of Cal.

The movement forces the defender to take their eyes off the disc and fully faceguard Cal, which is perfect because...

V. Well-timed continuation off the chisel cut [0:25]

...Nissen throws a dishy pass to Gordon's chisel cut, and Cal immediately breaks back to the right to offer Gordon a continuation.

I don't have any special subtleties to point out here, it's just a well-timed cut (and shows how the original "slide to the left" was likewise well-timed to set up counter-momentum back to the right). Gordon doesn't throw the pass but Cal is definitely open. Perhaps Gordon was worried about the mark selling out to block the throw:

VI. Fill off the upline; abort and go endzone [0:32]

Gordon instead throws an easy backhand to Nissen for no gain, setting up the final moment of our analysis, which again highlights high-level awareness and real-time adaptation.

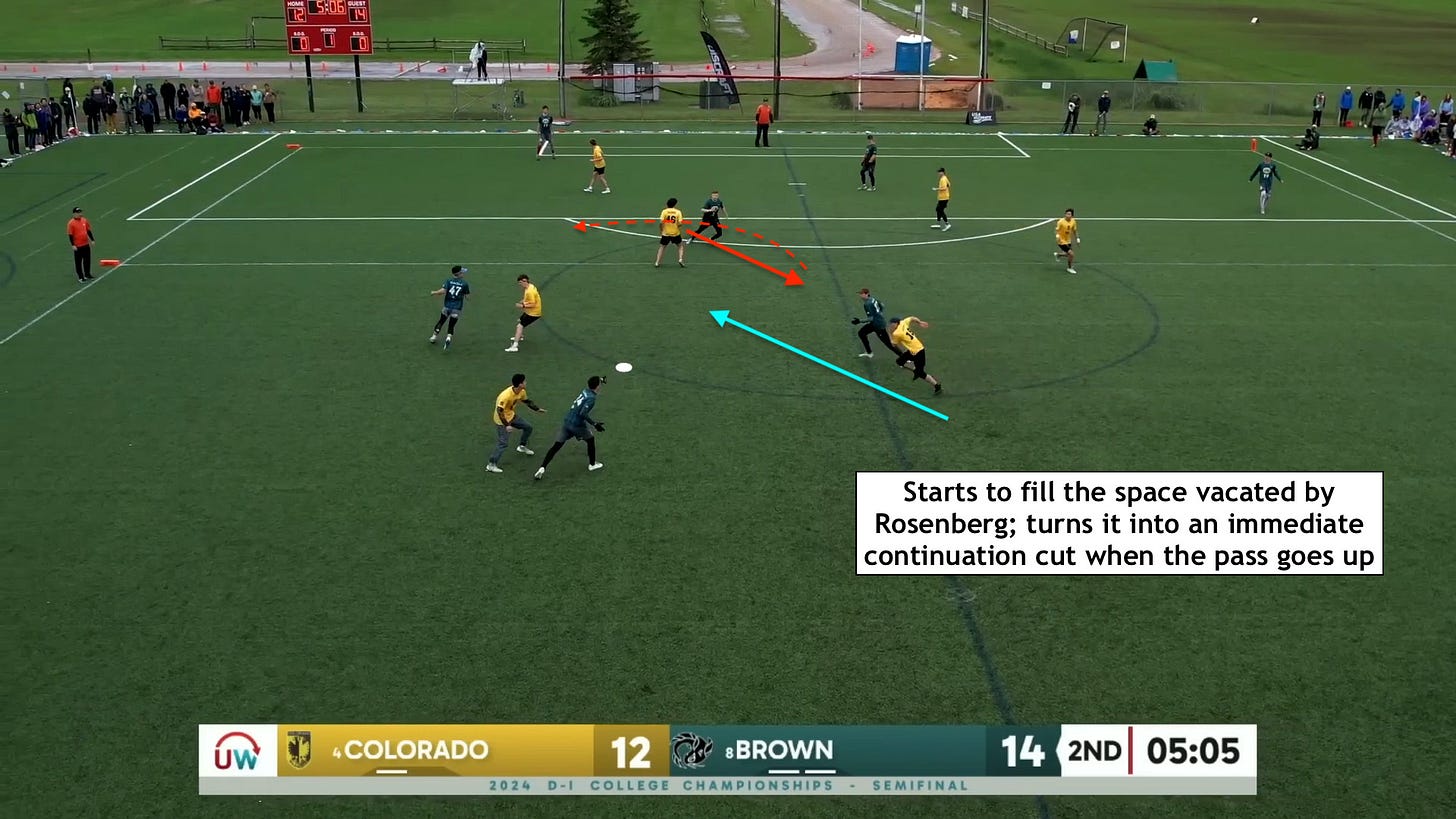

Nissen now has the disc, towards the left side of our screen. After Gordon dances for a bit, Rosenberg provides a second option by cutting upline from the handler space.

Cal sees Rosenberg starting the upline cut, and immediately accelerates towards the backfield to fill the space vacated by Rosenberg and be ready to offer Nissen a bailout option. Another correct read of the situation.

But Nissen finds just enough room to throw the lefty backhand to Rosenberg. Cal sees this, and, barely three steps into his attack of the reset space, he immediately re-orients and cuts back to the left side of the screen to offer Rosenberg a continuation pass into the endzone. Once again, elite-level adaptability—recognizing how the field was changing and responding to it in real time.

Rosenberg ends up throwing a "goal" to Gordon, but both Gordon and Cal both were wide open. The Colorado defender guarding Gordon calls a pick on the play, so if anything, it would've actually been better to throw it to Cal. (After the pick call is discussed and player restarts, Brown scores to win the game a few passes later.)

All in all, including both "decisions" and "re-decisions" as the situation evolved, that's something like 8 good decisions in 32 seconds. A great case study in constant awareness, reading the defense, and properly balancing attacking with deferring to teammates' attacks. Cal never even touched the disc but was locked in nonstop and never stopped probing for his chances.

Saving energy with probing cuts

One thing this clip really highlights for me is how much energy Brown can save by playing this style of frisbee.

Think of how much running it takes to make "one cut" from the back of the stack in your stereotypical vert stack offense. You cut under from the back of the stack—that's 15, maybe 20 yards. When you don't get the disc, you slash across the front of the stack in case there's an opportunity for a skinny inside throw (Clear out, don't check out)—that's another 10 or 15 yards. Then you curl back into the stack—another 5-10 yards, at a slower pace.

It took 30-45 yards of running, just to offer your thrower one option.

When Cal looks to attack the open space during Rosenberg's pivot, the whole "probe" lasts barely two steps—he accelerates hard, then aborts immediately when he sees Rosenberg isn't looking at him.

When Leo Gordon catches the dishy pass on the chisel cut, Cal's continuation offer is maybe 20 yards of running, at most—10 yards accelerating into the space, 10 yards jogging back to set up. And that's for a cut that really should've been thrown to.

I really like this style of constant probing while not wasting more energy than needed. See, for example, Don't not get thrown to, which focuses more on how not over-cutting helps the offense’s spacing. Although Cal does make the one actual cut that doesn't get thrown to, I don't think that's really his fault—since he was open—and overall he does a great job of not wasting energy on runs that are unlikely to result in him getting the disc.

Point five frisbee

When I've written about Point five frisbee, I've mostly focused on the thrower's perspective—moving the disc quickly. This clip of Cal really highlights how to bring a point-five mindset to cutting. He's locked in at all times (Oodles of OODAs). There are multiple times in this short window where he makes a decision, and then re-makes a decision barely a split second later as he reads what his teammates are doing.

He's aware of teammates, he's aware of defenders, he's aware of spaces, and he's got the flexibility to change his plan on a moment's notice as the situation plays out in front of him. He's got that point-five-mindset of understanding the importance of well-timed continuation attacking before the defense has time to catch up.

Final thoughts — Appreciating a great performance

Do you know who had the highest plus/minus at 2024 College Nationals? Well, it was Jacques Nissen.

But do you know who had the second highest +/-? It was Cal, with 27 goals, 12 assists, and just 3 turns. He had a higher +/- than many players who are much bigger "household names"4 like Scott Heyman, Calvin Brown, and Henry Ing5.

Obviously Brown's system does a good job setting its players up for success. But just as obviously, Cal is a cutting genius in his own right.

The clip embedded below is 37 seconds, but it's 32 seconds from the disc being tapped into play to the disc being caught in the endzone.

Though once play starts and Brown gets into their dominator motion, it no longer looks like a stack

Of course, no one can be expected to make the perfect read every time, and Rosenberg does a good job to patiently preserve possession for Brown

In the, uhh, frisbee households…

You might think that's because his team didn't ask him to take risks with the disc. That doesn't really seem to explain it, though. Henry Ing, for example, only had 7 turns—just 4 more than Cal. But Cal had 14 more goals and only 1 less assist.

Lucky PuNCs alum Cal Nightingale